- Published: 20 May 2025

- ISBN: 9781529926873

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $24.99

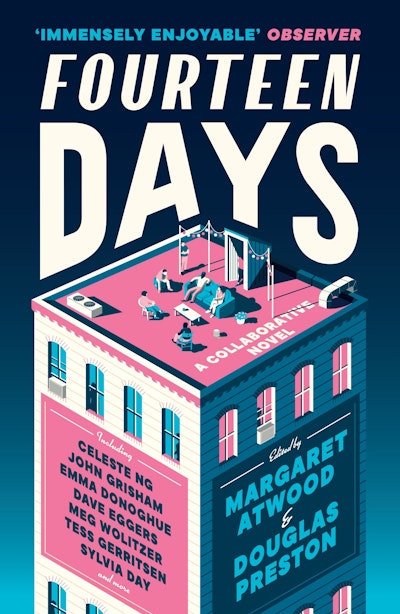

Fourteen Days

Extract

The pay in the Fernsby Arms is rotten, but I was desperate, and it kept me from winding up on the street. My father came here from Romania as a teenager, married, and worked like a dog as the super of a building in Queens. And then I was born. When I was eight, my mom left. I tagged along as Dad fixed leaky faucets, changed lightbulbs, and dispensed wisdom. I was pretty adorable as a kid, and he brought me along to increase his tips. (I’m still adorable, thank you very much.) He was one of those supers people liked to confide in. While he was plunging a shit- blocked toilet or setting out roach motels, the tenants liked to pour out their troubles. He’d sympathize, offering benediction and reassurance. He always had an old Romanian saying to comfort them, or some tidbit of ancient wisdom from the Carpathian Mountains—that plus his Romanian accent made him sound wiser than he really was. They loved him. At least some of them did. I loved him, too, because none of this was for show; it’s how he really was, a warm, wise, loving, faux-stern kind of dad—his one drawback being that he was too Old World to realize how much his ass was being mowed every day by Life in America. Suffice to say, I did not inherit his kindly, forgiving nature.

Dad wanted a different life for me, far away from having to fix other people’s shit. He saved like mad so I could go to college; I got a basketball scholarship to SUNY and planned to be a sportscaster. We argued about that—Dad wanted me to be an engineer ever since I won the First Lego League robotics prize in fifth grade. College didn’t work out. I got kicked off the college basketball team when I tested positive for weed. And then I dropped out, leaving my dad $30,000 in debt. It wasn’t $30,000 in the beginning; it started out as a small loan to supplement my scholarship, but the vig grew like a tumor. After leaving school, I moved to Vermont for a bit and lived off a lover’s generosity, but a bad thing happened, and I moved back in with my dad, waiting tables at Red Lobster in Queens Place Mall. When Dad started going downhill from Alzheimer’s, I covered up for him as best I could in the building, fixing stuff in the mornings before going to work. But eventually, a miserable toad in the building reported us to the landlord, and he was forced to retire. (Using my master key, I flushed a bag of my Legos down her toilet as a thank-you.) I had to move him to a home. We had no money, so the state put him in a memory care center in New Rochelle. Evergreen Manor. What a name. Evergreen. The only thing green about it are the walls—vomit-puss-asylum green, you know the color. Come for the lifestyle. Stay for a lifetime. The day I moved him in, he threw a plate of fettuccini Alfredo at me. Up until the lockdown, I’d been visiting him when I could, which hasn’t been much because of my asthma and the ongoing shit-saster known as My Life.

All these bills started pouring in related to Dad’s care and treatment, even though I thought Medicare was supposed to pay. But no, they don’t. Just you wait until you’re old and sick. You should have seen the two-inch stack I burned in a wastebasket, setting off the fire alarms. That was in January. The building hired a new super—they didn’t want me because I’m a woman, even though I know that building better than anyone—and I was given thirty days to move out. I got fired from Red Lobster because I missed too many days taking care of my dad. The stress of no job and looming homelessness brought on another asthma attack, and they raced me to the ER at Presbyterian and stuck me full of tubes. When I got out of the hospital, all my shit had been taken from the apartment—everything, Dad’s stuff, too. I still had my phone, and there was an offer in my email for this Fernsby job, with an allegedly furnished apartment, so I jumped on it.

Everything happened so quickly. One day the coronavirus was something going on in Wu-the-hell-knows-where-han, and the next thing you know, we’re in a global pandemic right here in the US of A. I had been planning to visit Dad as soon as I’d moved into a new place, but in the meantime I’d been FaceTiming him at Pukegreen Manor almost every day with the help of a nurse’s aide. Then all of a sudden, they called out the National Guard to surround New Rochelle, and Dad was at ground zero, blocked off from the rest of the world. Worse, I suddenly couldn’t get anyone on the phone up there, not the reception desk or the nurse’s cell or Dad’s own phone. I called and called. First it just rang, endlessly, or someone took the phone off the hook and it was busy forever, or I got a computer voice asking me to leave a message. In March, the city got shut down because of Covid, and I found myself in the aforesaid basement apartment full of weird junk in a ramshackle building with a bunch of random tenants I didn’t know.

I was a little nervous because most people don’t expect the super to be a woman, but I’m six feet tall, strong as heck, and capable of anything. My dad always said I was strălucitor, which means radiant in Romanian, which would be such a dad thing to say, except it happens to be true. I get a lot of attention from men—unwanted, obviously, since I don’t swing that way—but they don’t worry me. Let’s just say I’ve handled my share of fuckwad men in the past, and they’re not going to forget it any time soon, so trust me, I can handle whatever this super job throws at me. I mean, Dracula was my great-grandfather thirteen times removed, or so Dad claims. Not Dracula the dumbass Hollywood vampire, but Vlad Dracula III, king of Walachia, also known as Vlad the Impaler—of Saxons and Ottomans. I can figure out and fix anything. I can divide in my head a five-digit number by a two-digit number, and I once memorized the first forty digits of pi and can still recite them. (What can I say: I like numbers.) I don’t expect to be in the Fernsby Arms forever, but for the moment, I can tough it out. It’s not like Dad’s in a position to be disappointed in me anymore.

When I started this job, the retiring super was already gone. Guess not every building wipes out all the super’s stuff when they leave, ’cause the apartment was packed with his junk and, man, the guy was a hoarder. I could hardly move around, so the first thing I did, I went through it all and made two piles—one for eBay and the other for trash. Most of it was crap, but some if it was worth good money, and there were a few items I had hopes might be valuable. Did I mention I need money?

To give you an idea of what I found, here’s a random list: six Elvis 45s tied in a dirty ribbon, glass prayer hands, a jar of old subway tokens, a velvet painting of Vesuvius, a plague mask with a big curved beak, an accordion file stuffed with papers, a blue butterfly pinned in a box, a lorgnette with fake diamonds, a wad of old Greek paper money. Most wonderful of all was a pewter urn full of ashes and engraved Wilbur P. Worthington III, RIP. Wilbur was a dog, I assume, though he could have been a pet python or wombat, for all I know. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t find anything personal about the old super, even his name. So I’ve come to think of him as Wilbur, too. I picture him as an old man with a harrumphing, what-do-we-have-here manner, unshaven, evaluating a broken windowshade with his wet lips sticking out pensively, making little grunts. Wilbur P. Worthington III, Superintendent, The Fernsby Arms.

Eventually, in the closet I found a hoard of something far more to my liking: a rainbow array of half- empty liquor bottles, spirits, and mixers crowding every shelf from top to bottom.

The accordion file intrigued me. Inside were a bunch of miscellaneous papers. They were not the super’s scribblings, for sure—these were documents he’d collected from somewhere. Some were old, typed with a manual typewriter, some printed by computer, and a few handwritten. Most of them seemed to be first-person narratives, incomprehensible, rambling stories with no beginning or end, no plot, and no bylines—random splinters and scraps of lives. Many were missing pages, the narratives beginning and ending in the middle of sentences. There were also some long letters in there, too, and unintelligible legal documents. All this stuff was mine, I supposed, and I was sick when I thought of how this alien trash was all I had in the world, replacing everything I used to own that my dad’s building had thrown out.

But among the stuff in the apartment was a fat binder, sitting all by itself on a wooden desk with peeling veneer, a chewed Bic pen resting on top of it. When I say “chewed,” I mean half-eaten, my mysterious predecessor having gnawed off at least an inch from the top. The desktop was about the only neatly organized place in the apartment. The handmade book immediately intrigued me. Its title was on the cover, drawn in Gothic script: The Fernsby Bible. On the first page, the old super had clipped a note to the new super—that is, me—explaining that he was an amateur psychologist and trenchant observer of human nature, and that these were his research notes, collected on the residents. They were extensive. I paged through it, amazed at the thoroughness and density of the work. And then at the end of the binder, he had added a mass of blank pages, with the heading “Notes and Observations.” And then he’d added a small note at the bottom: “(For the Next Superintendent to Fill In.)”

I looked at those blank pages and thought to myself that the old super was crazy to think his successor—or anyone, for that matter—would want to fill them up. Little did I know the magical allure that a half-eaten pen and blank paper would have on me.

I turned back to the super’s writings. He was prolific, filling pages and pages of accounts of the tenants in the building, penned in a fanatically neat hand—with sharp comments on their histories, quirks and foibles, what to watch out for, and all-important descriptions of their tipping habits. It was packed with stories and anecdotes, asides and riddles, factoids, flatulences, and quips. He had given everyone a nickname. They were funny and cryptic at the same time. “She is the Lady with the Rings,” he wrote of the tenant in 2D. “She will have rings and things and fine array.” Or the tenant in 6C: “She is La Cocinera, sous-chef to fallen angels.” 5C: “He is Eurovision, a man who refuses to be what he isn’t.” Or 3A: “He is Wurly, whose tears become notes.” A lot of his nicknames and notes were like these—riddles. Wilbur must’ve been a champion procrastinaut, writing in this book instead of fixing leaky faucets and broken windows in this shithole of a building.

As I read through those bound pages I was transfixed. Aside from the strangeness of it all, they were pure gold to this newbie super. I set out to memorize every tenant, nickname, and apartment number. It’s my essential reading. Ridiculous as it is, I’d be lost without The Fernsby Bible. The building’s a shambles, and he apologized about that, explaining that the absentee landlord didn’t respond to requests, won’t pay for anything, won’t even answer the damn phone—the bastard is totally AWOL. “You’ll be frustrated and miserable,” he wrote, “until you realize: You’re on your own.”

On the back cover of the bible, he scotch-taped a key with a note: “Check it out.”

I thought it was a master key to the apartments, but I tested it and found out it wasn’t. It was a strangely shaped key that didn’t even fit into the many locks I tried it on. I became intrigued and, as soon as I could, I started going through the building methodically, testing it in every lock, to no avail. I was about to give up when, at the end of the sixth-floor hall, I found a narrow staircase to the roof. At the top was a padlocked door—and lo and behold, the key slipped right into that padlock! I opened the door, stepped out, and looked around.

I was stunned. The rooftop was damn near paradise, never mind the spiders and pigeon shit, and loose flapping tar paper. It was big, and the panorama was stupendous. The tenements on either side of the Fernsby Arms had recently been torn down by developers, and the building stood alone in a field of rubble—with drop-dead views up and down the Bowery and all the way to the Brooklyn Bridge, the Williamsburg Bridge, and the downtown and midtown skyscrapers. It was evening, and the whole city was tinged with pinkish light, a lone jet contrail crossing overhead in a streak of brilliant orange. I yanked my phone out of my pocket—five bars. As I looked around, I thought, What the hell? I could finally call Dad from up here, hopefully reach him at last, if it was just a reception problem keeping me from getting through at Upchuck Manor. It was certainly illegal to be up on the roof, but the landlord sure wasn’t going to be coming into the Covid- ridden city to check on his properties. With the lockdown now stretching almost two weeks, this rooftop was the only place a body could get fresh air and sun that felt halfway safe anymore. One day the developers would put up hipster glass towers, burying the Fernsby Arms in permanent shadow. Till then, though, why shouldn’t it be mine? Obviously, good old Wilbur P. Worthington III had felt the same way, and he wasn’t even here for lockdown.

As I scoped the place out, I immediately noted a big lumpy thing sitting out in the open, covered with a plastic tarp. I yanked it off, revealing an old mouse-chewed fainting couch in soiled red velvet—the old super’s hangout, for sure. As I eased down on it to test its comfort, I thought, God bless Wilbur P. Worthington the Third!

I began to come to the roof every evening, at sunset, with a thermos of margaritas or some other exotic cocktail I’d scrounged up from my rainbow room of liquor, and I stretched out on my couch and watched the sun set over Lower Manhattan while I dialed Dad’s number over and over again. I still couldn’t reach him, but at least I got a good buzz on while trying.

My solitary paradise, such as it was, didn’t last long. A couple of days ago, in this last week in March, as Covid was setting the city on fire, one of the tenants cut the lock off the door and put a plastic patio chair up there, with a tea table and a potted geranium. I was seriously cheezed. Good old Wilbur had kept a collection of locks along with his other junk, so I picked up a monstrous, case- hardened, chrome-and-steel padlock, heavy enough to split the skull of a moose, and clapped it on the door. It was guaranteed not to be cut or three times your money back. But I guess they wanted their freedom as much as I did, because someone took a crowbar to the lock and hasp and wrenched them off, cracking the door in the process. There was no locking it after that. Try buying a new door during Covid.

I’m pretty sure I know who did it. When I stepped out onto the roof after finding the busted door, there was the culprit, curled up in a “cave chair”—one of those seat things shaped like an egg covered in faux- fur that you crawl into—vaping and reading a book. It must have been hell schlepping that chair all the way up to the roof. I recognized her as the young tenant in 5B, the one Wilbur called Hello Kitty in his bible because she wore sweaters and hoodies with that cartoon character on it. She gave me a cool look, as if challenging me to accuse her of busting the door. I didn’t say anything. What was I gonna say? Besides, I had to respect her a little for that. She reminded me of myself. And it’s not like we had to talk to each other—she seemed as keen to ignore me as I was in ignoring her. So I kept my distance.

Fourteen Days No Author

Led by Margaret Atwood and Douglas Preston, a star-studded collection of writers come together to create a dazzlingly original, multi-voiced novel

Buy now