- Published: 1 May 2017

- ISBN: 9780143782179

- Imprint: William Heinemann Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $34.99

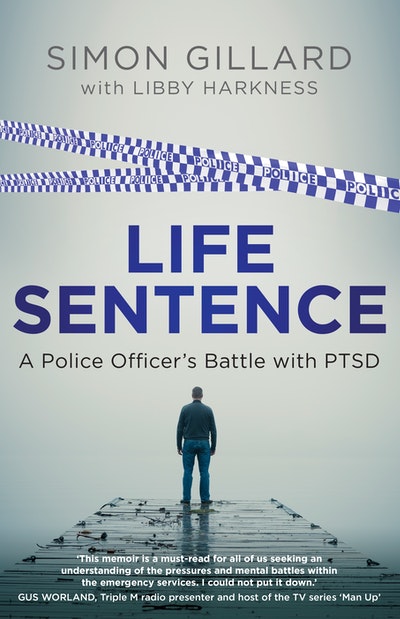

Life Sentence

A Police Officer’s Battle with PTSD

Extract

I immediately confessed the bad news to my parents, fearing the worst. A minor misdemeanour usually meant being banished to the front step to sit for two hours to think about my behaviour, while a serious breach such as this could mean getting the strap from Dad. Both of my parents were disciplinarians: Mum was a very religious woman who lived by a strict moral code, and Dad, who was a fitter and turner, was not known for overt displays of affection. He did try to bond with me in his own way by taking me to see the Manly Sea Eagles play – we’d go with my best friend David Harris and his father – but if Dad didn’t like our rowdy behaviour he would move away and sit separately.

Mum and Dad must have realised how petrified I was as they went easy on me. In fact, instead of being angry, Dad did something so uncharacteristic that I have never forgotten it: he tried to protect me. He suggested we might be able to limit the damage by apologising to the girl in advance and drove me immediately to her house. No one was there so we had to turn around and go home. We had only been back ten minutes when I heard the dreaded knock, knock, knock at the front door. Dad opened the door to find two policemen asking to see me. When I presented myself, barely able to look them in the eye, they proceeded to give me a very stern lecture: what I’d done was called ‘malicious damage’ and I could be charged. As it was a first offence the matter would not be taken any further, however my details would be recorded and should I ever break the law again I would be in serious trouble. I burst into tears – in my innocence I didn’t know that due to my age there would be no record of such a misdemeanour and that their goal was simply to put the fear of God into me. Mission accomplished! I was certainly terrified that whatever was on record might affect me getting into the police force.

Later, when Travis, Chris and I discussed the situation, I was surprised to find they were completely unperturbed.

In fact they seemed to find it all quite exciting, while I, by contrast, developed a constant nagging worry that my past would catch up with me eventually. I was determined to keep my nose squeaky clean from then on.

By high school my commitment to becoming a police officer was undiminished. I went to Pittwater House, a private co-educational high school on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, and had a large group of friends, who knew I wanted to be a policeman. They all thought it highly amusing as none of them had thought far enough ahead to see themselves in a real job.

As friends, we all had nicknames for each other, usually a contraction of our surnames by adding a ‘y’ or an ‘ie’ at the end, or else some other interesting association. For instance, Lachlan Yeates was ‘Yeatsy’; David Harris was ‘Harry’; Ben Wheeler was ‘Wheels’; Lucien Wiseman was ‘Ducey’; David Cox was ‘Coxy’ and Antony Burgess was ‘Burger’. And when I wasn’t ‘Gilly’, I was ‘Gobbledock’ – the name of a vertically challenged alien in an advertising campaign during the 1980s and 90s – because I was short and stocky.

It was my five foot nine height that incited the most ribbing. In spite of the fact that the NSW Police Force had abolished height restrictions in 1986, my mates still went on about me being too short. It was all good-natured – they knew I could take a joke – but it did make me feel as if I was out on a limb. By the time I was in Year 11, I was also conscious of my weight. I had been playing in the school’s Rugby First 15 and our football coach revved me up to get a bit fitter if I wanted to play half-back. So, during the next Christmas holidays I trained really hard and went on a strict diet over the eight-week break, and when I got back to school I had lost around 20 kilograms.

The weight loss attracted a lot of attention as I’d always been on the podgy side, and I laughed it all off, telling everyone I’d been on a cigarette and coffee diet. I was also aware that a few of the girls were looking at me with sudden interest. (One, a pretty blonde called Sarah Gilmour, who had always been a friend, even asked me out a year after we left school. I would have loved to have said ‘yes’, but as she had previously dated one of my good mates I felt I couldn’t out of respect for him.)

For my 18th birthday I decided to have a big party for about 100 friends and family at a hotel in Collaroy, which is also on the Northern Beaches. My friend Ben, who was quite artistic, offered to design the invitation. On the front of the card he drew a traffic cop on a motorbike and the words ‘Guess who’s 18?’. The card opened up to a sketch of a pair of women’s high heels poking out from an open car door on the driver’s side, and a cop (supposedly me) having a ‘conversation’ with her (okay, with his pants down) saying, ‘You have the right to remain silent – this doesn’t change a thing . . . you have the right . . . ooh . . . to keep going.’ Clearly my ambition to join the force was perfect ammunition for my mates.

I left school at the end of 1994 but, frustratingly, was a few months short of the eligible age for recruitment, which was 18 years and ten months. I put my application in as soon as I was able to in July 1995. During the waiting period – first for eligibility and then for acceptance – I worked in a local hardware store and also started a management training course in the hope that any sort of study would be useful in the force. The course required going to a private training college in the city twice a week. It was there I met Renee, a blonde, blue-eyed girl who worked in another of the chain’s stores. Renee lived in Wentworthville in Western Sydney – a long way from where I lived in Killarney Heights – but we started dating and she was my first serious girlfriend.

Like my school mates, the guys at work took every opportunity to rib me about my height. Ken, one of the salesmen, told me very seriously one morning that he’d heard on the radio that the police were reinstating the height restriction; it was now five foot eleven.

‘You’re kidding,’ I said, incredulous. ‘Piss off, you’re joking.’ But I rushed off to make a phone call to check anyway.

When I got back from lunch one day, Ryan, another work mate, told me he’d taken a phone message for me from the recruitment office, advising me I’d been accepted. I was very excited until I saw the look on his face and everyone started laughing. I got him back by writing ‘knobhead’ on his name badge, which he’d left on his desk when he went to lunch. He stuck it back on without looking at it and I had a good laugh when the first customers he approached started smiling and snickering.

When I did finally get the call-up letter to present myself for an interview, I was over the moon. I proudly showed it to everyone and celebrated with my mates at the pub that night.