Leah Purcell reflects on the tiny story that continues to form part of her contemporary dreaming.

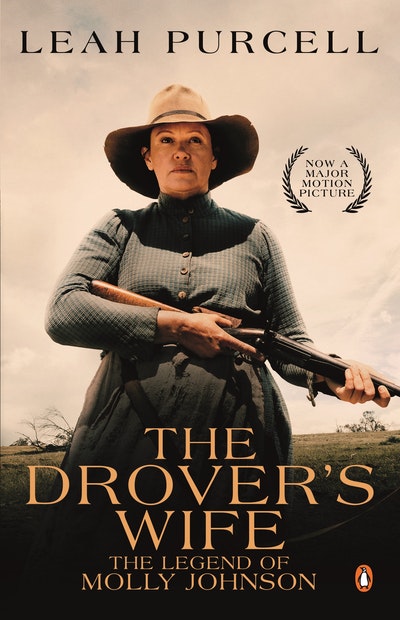

You might think Leah Purcell’s relationship with Henry Lawson’s short story, The Drover’s Wife, started with her multi-award-winning stage adaptation. You could be mistaken to thinking that her forthcoming big-screen translation of the story marks the end of her Drover’s Wife journey. With her novel of the same name fresh on shelves, and a just a week after wrapping the film, we caught up with the acclaimed actor, screenwriter, playwright and now novelist, to ask about her ongoing Drover’s Wife connection. Here are five surprising things we learned.

1. Purcell has carried Lawson’s short story with her for life.

‘I was the youngest of seven, but my brothers and sisters are a lot older than me so I spent a lot of time at home with just me and my mum. My mum was my mother, she was my father, she was my hero.

‘I saw me and my mum in The Drover’s Wife. We had a wood heap, we had a combustion stove. I’d be out there splitting logs and I’d watch my mother with boiling water in a copper pot. So, to me, my mother was the Drover’s Wife, and I was little Jack from the Henry Lawson story. It was me and her against the world. I think that’s why I connected with it.

‘My mum would read the short story to me, and I’d say the famous last line: “Ma, I won't never go drovin’.” I was a mongrel sleeper, tapping her at midnight saying, “Mum, tell me that story.” And she’s going, “Go away!” I’d be acting out that last line, reciting it her. And she’s saying, “Go back to sleep.”

‘My mother would read it and just tear up – she was moved by it… I found the book years later, after she passed away, and I remember grabbing that little book. But she had passed before I could say: “Why Henry Lawson? Why this little book of short stories?”

‘Now it’s been with me for 42 years. Someone said to me the other day: “When did you take ownership of Henry Lawson’s story?” I said, “Mate, when I was five years old. And I’ve got the book to prove it.”’

2. Another seed of Purcell’s Drover’s Wife journey was planted while shooting the Ray Lawrence film Jindabyne in the Snowy Mountains in 2006.

‘When I did the movie up there, me and my partner went for a walk around the national park, and I said, “We don’t utilise this country enough in our films or stories. I’m gonna come back here and do something. And I think I’m gonna write it, and I think I’m gonna be in it, and I think it’s going to be The Drover’s Wife.” That was 2006. We finished shooting the film in the mountains just last week [in December 2019]. So, how’s that for putting it out there, on country?!’

3. Working in what’s typically reverse order for story adaptation, Purcell started with the play, then expanded that into a film before fleshing out the novel.

‘It was very nerve-wracking – I’d never done a novel before. But then I looked at all the character breakdowns I’d done for the actors and I thought I could work those into the book – so I got excited by the prospect. I also went back and looked at all the monologues I’d written for the play, to see if they hold up. I had a well of writing across the platforms, so I just stole and borrowed and reused some of the stuff.

‘Writing for television, I was always getting in trouble. They’d say, “C’mon, you’re not writing a novel. Get to the point. You’re too descriptive.” So I had to retrain my brain. But when I realised I could expand the narrative for the novel, it was very freeing. All the stuff I took out for the play, or that didn’t make the screenplay, I could shove in. And more. That was very rewarding.

‘Internal thoughts were the thing that bugged me. In my first gig writing for TV, our script supervisor, who was awesome, said to me when I had a character talk to themselves, “If you ever do that again, I’ll shoot ya.” So I went, “OK, note taken.” Then I had permission in the book, because my editor told me I could use internal thoughts. I said to her, “The last time I did that, someone threatened to shoot me.”’

4. An editor’s request for an extra paragraph led to the beginnings of something much greater.

‘My editor at Penguin said, “Can you give us a paragraph about when the kids go up to the mountains and what happens next?” I gave them an extra 10,000 words. The editor was saying, “This is the first part of the second book, mate. We only wanted a paragraph.” I said, “I’ve got stories, don’t worry about that.”

‘Now we’re working on the TV series as well. I’ve got two or three seasons very loosely drawn up, where I describe what happens to the kids twenty years into the future… Danny the oldest boy never told his brothers and sisters the true story about what happened to their mum. So now they all come into town and they find out through the town whispers: the quadroon Kids of Molly Johnson – the woman who went out on a man-hating murder spree – are back. That’s the talk of the town. And Danny wants to get justice through the legal system, but Joe Junior wants revenge.’

5. Purcell now describes her relationship with The Drover’s Wife as part of her contemporary dreaming.

‘I couldn’t say I was conscious of it when I was writing the play, but I guess there was a structure to what I was doing that was part of my dreaming journey. That format of how Blackfellas hand down stories – and why it’s important to tell someone a story, so they can continue that journey, even if they’re not within the family. In the case of Molly Johnson’s story in the novel, Ginny May was witness to it, and then she handed it to a stranger – who became a sort of story keeper – with the hope that one day that story would be given back to Molly or to her children. So it’s this bearing witness, give-and-receive kind of format… With the next part that I write, I’ll be looking to come to some form of completion – for the family and Danny to inherit Molly’s story and try to make it right.

'In terms of me, dreaming is also everyday living and what I do today. My corroboree or my giving is telling my stories through this modern technology… keeping the stories alive and preserved for the next generation.

'I do like history and researching my own family stuff. And there are family elements throughout the novel that were given to me. The character Yadaka is based on my Aboriginal great grandfather. He was given to a South African circus – all of that part is true… There was stuff my father told me, and family stories – especially the stuff about the relationship between Molly Johnson and her dad, which came through family research. And for the play, I wanted to play Molly Johnson and I wondered how I could do it. So I thought, what if she had a Black mum – an Aboriginal link? My mum’s Aboriginal and my dad’s white.

'When I was growing up it was very rare to find books by Indigenous mob published by major publishing houses… We are storytellers. I come from a long line of storytellers, and I’m just lucky that I’m part of a generation where our stories are not just orally passed down – they can be preserved for our children and grandchildren and great grandchildren. It’s exciting times.'