Artist Ben Quilty pauses to reflect on the human stories that continue to influence and inspire his craft.

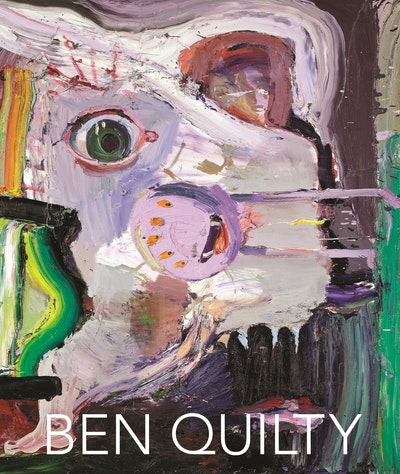

Ben Quilty is one of Australia’s most acclaimed contemporary artists. Winner of 2007’s National Self Portrait Prize, 2009’s Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, 2011’s Archibald Prize and 2014’s Prudential Eye Award, he has exhibited at the Australian National University, the Adelaide Biennial and the National Gallery of Victoria, as well as in several prestigious institutions overseas. In 2019, his body of work will be showcased in the major exhibition QUILTY, curated by Lisa Slade at the Art Gallery of South Australia, before embarking on a national tour. To coincide with the retrospective’s March unveiling, Quilty’s paintings will also be celebrated in a self-titled coffee-table book. For a man who’s lent his profile to several social causes, including abolition of the death penalty in Indonesia and the dispossession of Syrian children, the exhibition and book present rare opportunities to focus on the simple pleasure he derives from creation.

‘I find that I speak a lot, but I rarely get to speak about art,’ he says. ‘The act of making work, what happens in my studio, the beauty of materials, of pigments, of the ancient tradition of making pictures – this book is all about that… I just realised it could be a real opportunity to ease my anxiety about the planet for a while and think about what it is to make beautiful paintings.’

Of course, it’s these very anxieties and emotional responses to the world that inform the work itself – a process he’s described as ‘working out how to live in this world.’ As such, his paintings both individually and en masse evoke powerful emotional and narrative threads.

Long-form visual storytelling

For Quilty, storytelling is a fundamental quality inherent in good art. To begin with, he says, it’s an effective way to engage with an audience. On an artwork-to-artwork basis, he points to Indigenous Australian paintings as great examples of storytelling being integral to deeply appreciating art. In recent times he’s been exploring the art of central Australia’s Anangu people of the APY Lands, as well work from further north in Arnhem Land. ‘The story is so, so fundamental to the reading and understanding of these paintings,’ he says. ‘You need to understand the story to understand what the artist is trying to say. Tjunkara Ken, Sylvia Ken, Betty Pumani, Pepai Carroll, there are so many artists out there that I’ve spent a lot of time looking at recently, who’ve been a huge inspiration for my work.’

In his 2019 retrospective, twenty-odd years’ worth of Quilty’s works will be shown side by side. In this setting, the individual narratives interweave to reveal a grander story of his artistic practice, to be read in chapters, as we would a novel. It’s the curator’s ‘magic craft’, he says, to reveal new ways of experiencing a body of work as a satisfying whole. ‘Curators need to dip in and out of your practice to find passages of your work that will make sense to an audience,’ he says. ‘They have an eye for the work evolving or unfolding through time... Generally, I have no control over those things – I completely trust the curator to do that. And that’s really important to me, because in the studio there is so much control: you’re controlling every mark, every message that comes out. Then to have a very smart curator take that work and breathe new context into the way that it’s seen is very exciting and also challenging.’

Solitary acts exploring universal themes

Quilty describes his studio as essentially a diary for his ideas. In much the same way as a writer, like his friend and occasional collaborator Richard Flanagan, keeps a notebook, never letting an idea go to waste, the studio is the place where ideas are noted, investigated, cast aside, revisited. And the relative few finished works that emerge are actually the result of this methodical behind-the-scenes practice, just as the novelist may spend months and years reworking and refining their text before it sees the light of day.

Introduced by journalist and TV presenter Jennifer Byrne, Quilty met Flanagan at the Ubud Writers & Readers Festival in 2013. ‘I’d just finished reading The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which is one of those books that knocked me over,’ Quilty says. ‘And then, to meet the author was just daunting – I didn’t know what to do or say. I vaguely remember getting down on one knee, which is mortifyingly embarrassing. But Flan’s let me forget about that, which is very kind of him.’

Both Flanagan and Quilty are known for their deep contemplation of humanity through art, their social causes, and a fair level of self-deprecating humour and sardonic wit. As Byrne suspected, they found much in common. Quilty now acknowledges the author for helping him navigate life in the public eye. ‘Our work is made in private, on our own,’ he continues. ‘And then, there’s this intense public gaze when you have to speak about the art. We’re not saving anyone’s lives, but we both believe that the arts is such a fundamental part of the health of the community. When people read novels and look at art, they think outside themselves. They consider the world through all the complexities of literature and art. But at the same time, it’s important not to take yourself too seriously, especially when you’re from Tasmania.’

When we evoke empathy, we generate hope

In his art, Quilty has entered many of humanity’s darkest places to explore the complexities of the world as he sees it. In 2011, he travelled to Afghanistan as the official Australian Defence Force war artist. In Bali’s Kerobokan Prison he met, befriended and mentored convicted and condemned ‘Bali Nine’ heroin smuggler Myuran Sukumaran. In 2016, he accompanied Flanagan to Greece, Serbia and Lebanon to meet victims of the Syrian War, fleeing for their lives. Quilty says his attraction to extreme situations stems from his curiosity about his own humanity and the complexities of the privilege of being alive. When confronted by the darkest of times, we’re forced to contemplate life’s biggest questions.

‘In Afghanistan, all of the soldiers I met had been involved in contact and firefights, battles,’ he says. ‘So I got to ask questions of men and women that everyone in the community would like to ask: “Have you been with someone when they died?”, “have you ever killed anyone?”, “is your job in Afghanistan worth risking your life?” For Myuran: “Was your crime worth facing your mortality?” They’re huge questions, and people living in those circumstances often have a clearer understanding of the possible answers to those questions that I think we all have… Often the best art doesn’t give an answer. I hope that my art will be a bridge into the complexities of those sorts of questions that I couldn’t possibly begin to answer.

‘Part of my own belief about how we live on this planet always revolves around ideas of empathy, and that’s something I think is really missing today. People too quickly jump to a polarised view of the world and I think the complexities of being human means people often also jump to an angry extreme rather than feeling for other people. It’s not that hard, it’s actually really enjoyable to feel other people’s pain, feel their joy – it’s life-affirming.

‘With Myuran, it was about getting to know this young man and speaking to him in great depth about his feelings, what he’s facing and his sense of himself. There’s a truth to that, which the public back here in Australia had no idea about and really in the beginning had no interest in. I’m just retelling his story. Once you give someone the chance to speak and you listen to them, then there’s more chance you’ll be able to employ empathy to be able to see that person… People could talk about Myuran the bad drug dealer, but in the end he left behind something that is irrefutably good, and it’s a body of paintings that’s about himself and about his feelings. It just punches into the world his humanity and his legacy and makes people remember that when someone is down and out like Myuran was, they are still capable of love, they still have sadness and sorrow.’

Art can be a powerful agent of change

Whether in prisons, warzones or refugee camps, Quilty has found people in crisis wanting their stories heard. On a basic level, for those who feel voiceless, sharing their story is akin to empowerment. As a conduit for these truths, it’s also possible to shift the perceptions of others. Beyond the creation of beautiful objects, art can be a powerful tool in evoking empathy and outrage, anger and resistance. Even, in its highest sense, instigating change. For Quilty, the groundswell of powerful voices speaking out brings him hope that the stories of his children’s generation will be far more positive than those of today.

‘Richard and I discuss this a lot: at the moment it feels like there’s a revolution,’ he says. ‘For good reason; it’s a very fraught time, and I just want to empower my children to be good people, speak up for people, speak up for themselves.

‘We have to celebrate everything with cynicism. There have been incredible achievements, we are extraordinary, we have self-awareness and we have made music and art. And since the Industrial Revolution, we’ve made trains and steel and we’ve done great things. But we have to be self-aware and recognise the damage that we’ve done as well…

‘I often talk to my children about the earth being like an orange: on top of the skin is the thinnest, thinnest layer of air that we breathe and that sustains all of our existence. Since the Industrial Revolution, we have been pumping that thin skin with poison gas, and we don’t expect to have to pay a price. And we have these far-right commentators who shout at us to thunder on with blind optimism – “Only think positive thoughts about your future!” Well, there aren’t that many people in the art world who adhere to that crazy self-destructive belief in ourselves. I’m hopeful because right now everybody is empowered to speak up.’