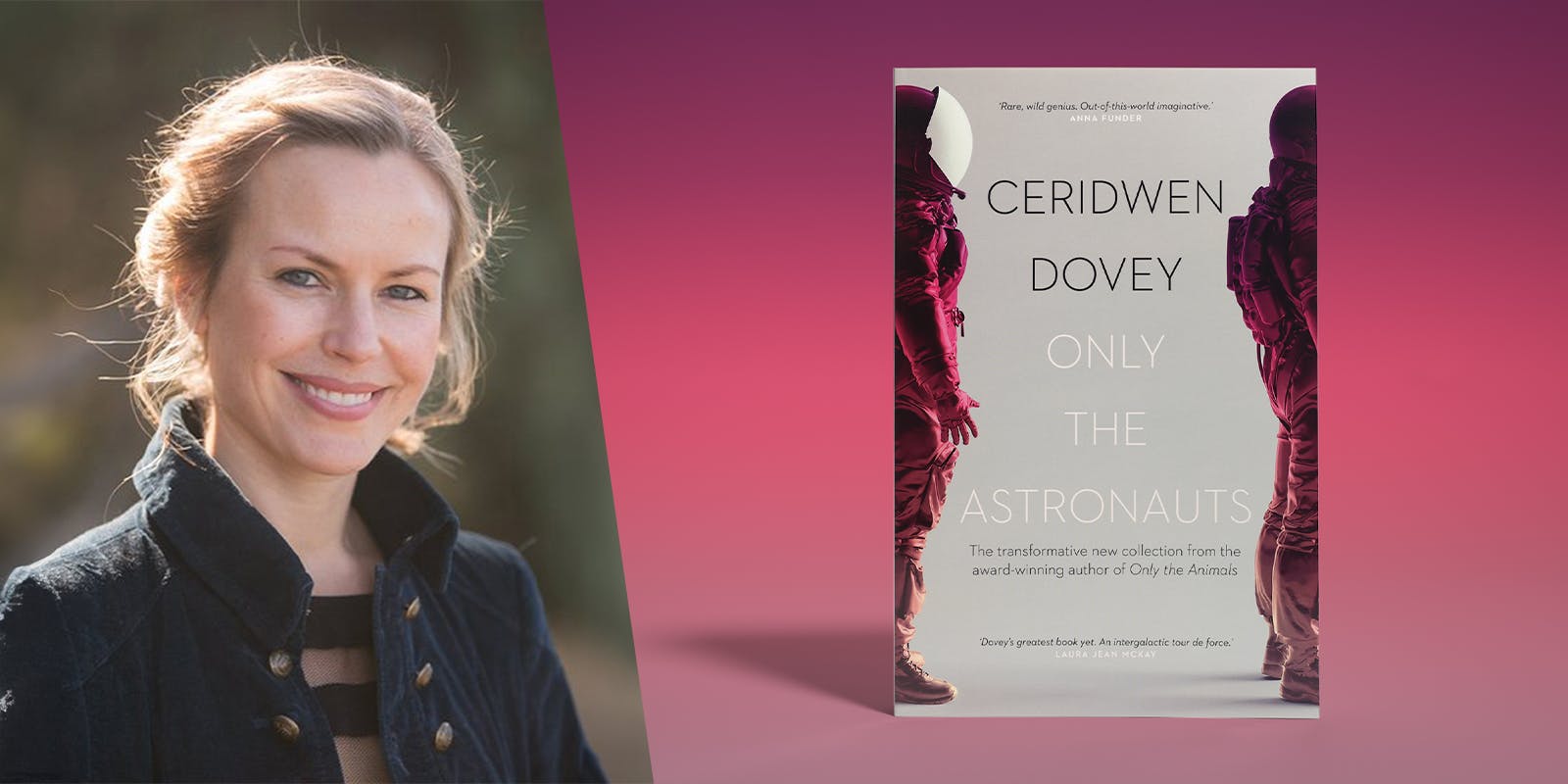

We caught up with the author to learn about her upcoming book, Only The Astronauts, why she chose to write about space and her unique narrative perspective.

What inspired you to write Only the Astronauts from non-human perspectives?

As a writer, I've always been really interested in empathy and how literature takes us into other people's minds in a way that nothing else can.

For me as a reader, the joy of reading has always been the sense of meeting another mind halfway, but in solitude.

So when writing, I've always wanted to find ways to reproduce the feeling that I get when I read literature but also experiment and push the limits of what empathy might be, testing how far the reader will follow me into a certain narrator's consciousness.

I think of Only the Astronauts and my previous book, Only the Animals – which came out in 2014 – as collections of fables. The origin of the word fable is ‘to give voice’, and I chose to use animal narrators in Only the Animals and object narrators in this new book because it's a way of giving them sweetness and earnestness and innocence, but also wisdom. Sometimes, it's quite hard to combine all of that into a human narrator.

Why did you set the book in space?

I remember the moment, about ten years ago, when I read about plans for commercial companies to mine the moon. I had a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach. 'I can't believe we're doing this again,' I thought. ‘We can't do this. We can't let outer space become another failed realm where we destroy another global commons the way that we have the ocean on Earth.’

In these stories, I'm asking people to explore these themes, but I'm trying to step away from any of that didactic mode of expression that I might use in nonfiction or journalism.

Did your background in journalism and nonfiction writing prepare you for researching this book? Did you have certain things that you knew you wanted to explore, or was it an entirely separate research process?

It's wonderful, as a writer, to work across the divide between fiction and nonfiction. I do a lot of science writing, and I used to feel like my greatest weakness was that I hadn't put my hat fully in the ring of any one mode of writing.

As I get a bit older, I'm starting to appreciate what each form gives me. Every time, fiction gives me this sense of enormous relief in the exploratory nature of it.

With this book, a lot of the stories come from material that I discovered when researching as a journalist or essayist but never used.

I often felt that I’d found something, but it wouldn’t fit into that article or essay form. Eventually, the bits and pieces that had been left out for different reasons accumulated into this wonderful, strange form – and that's where the stories came from.

Each one is based on a real space object that has been launched into space by humans, so they're all informed by real history. But then I take that history into a speculative zone and use a lot of creative and poetic license.

Is there a particular story in the book that you're excited to hear from readers about?

I think it would probably be The Fallen Astronaut.

The story is told from the perspective of Neil Armstrong's spirit, who, after death, has found himself inhabiting a little statue that is actually on the moon. It was the first art object left on the moon and was put there to honour the astronauts who died in the course of duty in their training.

In the story, I explore the idea that if a nature writer like Robert Macfarlane or Barry Lopez had been the one to step onto the moon and to try to describe it, to find language for it – rather than these well-meaning, but basically military-test-pilot guys, Neil and Buzz – how might they have gestured towards a language for what they saw on the moon?

I'm trying to have Neil leave behind that old identity, the inability to find the right words, and draw on the modes of nature writing, to find poetry that speaks to what he is seeing on the moon.

There’s a political reason behind it. If we have a natural language for the moon, if we begin to see the moon as a nature place, a wilderness, we can begin to think of conserving it as a wilderness, just as we had to make that change in our thinking about the ocean.

Another story in the book that's very close to my heart is the longest story, Requiem. It's written from the perspective of the International Space Station (ISS). It imagines the ISS giving one last tour of itself before it's deorbited, so it's set slightly in the future.

As I started to write about the ISS, I felt so much love for the humans who lived within its walls.

I think the thing that we've learned from the ISS is the kind of mutual care that surviving in space takes. Most pop-culture, sci-fi movies and TV shows have a much more dystopian view of what humans do to each other in space.

So just that sense of humans caring for each other, making room for each other under difficult circumstances . . . nothing really goes wrong. No one behaves particularly badly. But at the end of the story, the remaining astronauts who are about to leave the space station all write a poem of farewell to the ISS, each in their own language.

It was lovely to work with friends and colleagues to translate the sonnets into different languages, to capture that sense of the ISS as a home for all humans and a place where diversity was thriving, and is still thriving, and will thrive until it comes down. I think that's something we can hold on to.