- Published: 4 July 2023

- ISBN: 9780143787112

- Imprint: Hamish Hamilton

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 464

- RRP: $36.99

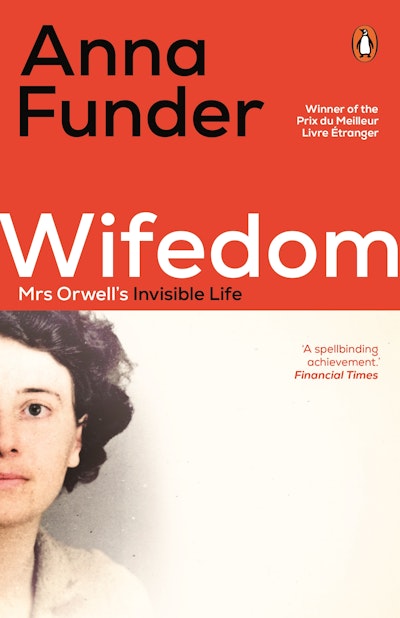

Wifedom

Mrs Orwell's Invisible Life

Extract

All of this was taking me away from work deadlines ticking under every waking minute. I shopped for groceries, yet again, in the soul-sapping local mall. I wound the car, yet again, down the ramps from floor to floor, following EXIT signs I knew were empty promises: I could never, really, leave. When the greedy boom-gate machine inhaled my ticket, I knew: the mall had sucked out my privileged, perimenopausal soul. I had to get her back.

So instead of going home I pulled in around the corner at a second-hand bookshop, Sappho. The ice cream could melt in the boot; the meat could sweat in its toxic plastic. Sappho Books is a relic from my mother’s liberation era, the 1970s. It is an unrenovated warren of a terrace house, with handmade signs sticking out from the shelves and a café with potted palms tucked in its wobbly, welcoming courtyard. To climb the creaky wooden stairs to nonfiction is to go back to a gentler, pre-digital era of shabby armchairs and serendipitous discovery. This place is a trove of works sifted from the mass of forgettable books published every decade and found to transcend their time. It is what you missed or never got to, it is what you don’t even know you need. Sappho is the opposite of a mall: no one is trying to sell you anything. In fact, the tattooed woman at the till sighs ruefully when you buy one of their books, as if money couldn’t, possibly, make up the loss. This place is entirely soul.

In that upstairs back room I found a first-edition, four-volume series of Orwell’s Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters from 1968. I’ve always loved Orwell – his self-deprecating humour, his laser vision about how power works, and who it works on. I sank into an armchair. The pages, dark and fragile, smelt like the past. I opened to the essay ‘Shooting an Elephant’. It begins:

In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people – the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me. I was subdivisional police officer of the town . . .

That voice! I dropped the groceries at home, and took Orwell and the French exchange student to the Dawn Fraser Baths on the harbour. The exchange student would swim, maybe cheer up. I would sit in the shade of 140-year-old bleachers and read Orwell’s making, piece by short piece, of his writing self.

Towards the end of the day I came to the famous essay ‘Why I Write’. ‘I knew,’ Orwell says, ‘that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life.’

I looked over the sparkling water to Cockatoo Island and considered today’s everyday failures – toxic plastic, soul-murder in a car park, the poor French exchange student doing lap after miserable lap. To say nothing of the work undone, piling up now in anxious, redflagged messages in my inbox. I needed to face the ‘unpleasant fact’ that despite Craig and I imagining we divided the work of life and love equally, the world had conspired against our best intentions. I’d been doing the lion’s share for so long we’d stopped noticing. For someone who notices things for a living, this seemed, to borrow our nine-year-old son’s term, an ‘epic fail’.

I looked back at the page.

‘After the age of about thirty,’ Orwell writes, most people ‘abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery.’

‘Anna?’ I looked up into the wet shadow of Benoît and handed over my credit card – to buy time, with ice cream.

‘But there is also,’ Orwell continues, ‘the minority of gifted, wilful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class.’

If I couldn’t see my own fury clearly enough yet to excise it, I thought, at least I could give it company. And then:

My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention . . .

I closed the book. I had a plan. If my three children – two teens and a tween – were going to emerge from childhood and see me for what I am, I would have to become visible to myself. I would look under the motherload of wifedom I had taken on, and see who was left. I would read Orwell on the tyrannies, the ‘smelly little orthodoxies’ of his time, and I would use him to liberate myself from mine.

As summer shifted into autumn I read the six major biographies of Orwell, published between the 1970s and 2003. They are by Peter Stansky and William Abrahams (1972 and 1979), Bernard Crick (1980), Michael Shelden (1991), Jeffrey Meyers (2001), D. J. Taylor (2003) and Gordon Bowker (also 2003). I’ve long loved Orwell’s writing so it was a joy to learn about the man described as ‘one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century’, and ‘a moral force, a light glinting in the darkness, a way through the murk’. I read of Orwell’s childhood in the 1910s, his time at Eton, then in Burma as a young policeman. I read that he married Eileen O’Shaughnessy in 1936, fought the fascists in the Spanish Civil War, then lived in London under fascist bombardment there, writing his masterpiece, Animal Farm, and, later, the dystopian marvel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Then, as winter set in, I came to this, which Orwell wrote during his final illness, after the marriage was over. He wrote it in his private literary notebook, in the third person, as if to distance himself from feelings that were hard to own.

There were two great facts about women which . . . you could only learn by getting married, & which flatly contradicted the picture of themselves that women had managed to impose upon the world. One was their incorrigible dirtiness & untidiness. The other was their terrible, devouring sexuality . . . Within any marriage or regular love affair, he suspected that it was always the woman who was the sexually insistent partner. In his experience women were quite insatiable, & never seemed fatigued by no matter how much love-making . . . In any marriage of more than a year or two’s standing, intercourse was thought of as a duty, a service owed by the man to the woman. And he suspected that in every marriage the struggle was always the same – the man trying to escape from sexual intercourse, to do it only when he felt like it (or with other women), the woman demanding it more & more, & more & more consciously despising her husband for his lack of virility.

Orwell only ever lived with one wife. These comments refer to Eileen.

I scoured the biographies. Some of them include parts of this extract. Could they help work out what was going on? One of them follows it with this observation: ‘Referring later to a notorious Edwardian murderer, he wrote of “the sympathy everyone feels for a man who murders his wife” – clearly Orwell in misogynist mood (even if ironically so), a mood he normally made an effort to muffle or suppress.’ This was bewildering, and not much help. Another biographer implies it’s fictional, possibly ‘passages for some other novel or short story, of mildly sadistic sexual fantasy’. But then, perhaps worried by Orwell’s confessed ‘lack of virility’, he tries to blame women for that, saying that these comments ‘reflect upon a type of woman who is sexually over-demanding’. Less than helpful. A third biographer writes: ‘Wives, [Orwell] suggested, use sex as a means of controlling their husbands.’ This is the misogynist trope of a woman ‘controlling’ a man when what she is controlling is access to her own body – so, no help at all, particularly when Orwell is saying he does not want his wife’s body. There seemed to be no way for the biographers to deal with the anti-woman, anti-wife, antisex rant other than by leaving it out, sympathising with the impulse, trivialising it as a ‘mood’, denying it as ‘fiction’ or blaming the woman herself.

Orwell’s thoughts are painful to read. Women disgust him; he disgusts himself. He’s paranoid, feeling he’s been tricked by a politicosexual conspiracy of filthy women ‘imposing’ a false ‘picture of themselves’ on the world. He sees women – as wives – in terms of what they do for him, or ‘demand’ of him. Not enough cleaning; too much sex. How was it, then, for her? My first guess: too much cleaning and not enough, or not good enough, sex.

This is how I moved from the work to the life, and from the man to the wife.

Wifedom Anna Funder

<h2>A blazing, genre-bending masterpiece from one of the most inventive writers of our time.</h2>

Buy now