- Published: 25 July 2023

- ISBN: 9781761340154

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 256

- RRP: $26.99

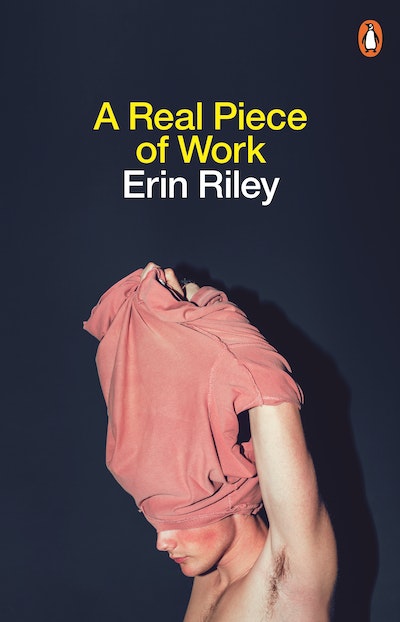

A Real Piece of Work

A Memoir in Essays

Extract

Erin, it’s Mum.

Sorry love, it’s me, Mum, I should have responded sooner, lovey. Speak with you soon. It’s Mum here, love, speak later. Mum.

Sometimes she even worked into her voicemails, both her title, in relation to me (my mother) and her actual name, Antoinette, as if I needed more help.

Mum had been in Canberra with her friend Jessie at the Botticelli to Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery.

Mum shot me a text, a photo of her next to Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, all smiles. The yellow, she tells me when I next visit, was ‘luminescent’, as if backlit by the sun.

I love that my mum, who is seventy-two, has a best friend who is her thirty-year-old piano teacher. Jessie drove them to Van Gogh in her new Mercedes. Jessie had gifted Mum the tickets for her birthday. She had scoffed at the idea of staying in a motel and booked a lush, serviced apartment with one king-sized bed. I imagined my mum, strapping on her CPAP machine, struggling into the bed, with Jessie cocooned in a plush hotel doona on the other side. Them laughing together into the night.

I wrote to Good Weekend magazine during the first wave of COVID in 2020, suggesting Mum and Jessie for their popular ‘Two of Us’ profile. My mum, this outspoken white, fat, retired nurse with a heart of gold, and her Chinese piano teacher, whose wealthy family constantly bribe her to get married.

The editor wrote back; they had too many (ha!) ‘Two of Us’-es. And so, the story is mine to tell.

Mum and Jessie have season tickets to the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Pre-COVID, Mum had, at the classical music radio station she volunteered for, ‘won’ a yearlong subscription at their silent auction – which she had in turn gifted Jessie. I later found out her bid was a generous twice the going rate. My dad drives them into the heart of the Opera House car park and drops them next to the lifts.

In the early days of their friendship, Jessie was learning to drive. Before the Mercedes, she learnt to drive in my mum’s Smart Car. She would chauffeur them around to classical music concerts in obscure suburban community halls. To see the seventy-nine-year-old Argentinian concert pianist Martha Argerich play the Concert Hall. Sometimes Mum paid for piano lessons in driving time.

Jessie and Mum do a lot of texting. It’s long since gone beyond co-ordinating the next piano class. Mum, one for long, novelesque messages, now sometimes flicks off an emoji. I know this is Jessie’s influence. A wilted rose, followed by a correction – one standing up – then a text-based rationale for the original emoji misdemeanour. Jessie fixed Mum’s GPS and taught her how to talk on the phone using Bluetooth in the car. Mum can send photos and now forwards on photos of my niece and nephews coupled with a short history of noticeable developmental milestones.

Last week, in preparation for the arrival of my parents’ new couch, Mum texted me, asking whether I might post the old couch on a closed Facebook group I am a member of. ‘Sure,’ I replied. She sent through two blurry photographs of the couch, which had been covered in a recently washed but still hideous linen overlay adorned in brown swirls. I asked her for a few better shots and some measurements. That she sent though, reluctantly, with a reminder, ‘Remember Erin, it’s Facebook, not Vogue!’

Jessie has been in Mum’s life for a few years now and has become a part of our family. I will visit my parents and Jessie will be there having a cup of tea. My dad’s a teacher, and often I’ll see them at the kitchen table, noses glued to Jessie’s laptop, workshopping edits of an essay draft. I know Dad is thrilled to be of help. He had long been let go as guest editor by me and my sister, now a school teacher herself. Jessie has brought something so beautiful to both my parents.

One time I visited them and found a fluffy ginger cat scurrying around the unit.

‘Who’s that?’ I asked.

‘Oh, that’s Brahms!’ quipped Mum.

Jessie had gone away for the weekend and my parents were happily cat sitting. For almost twenty years, they had two cats of their own, both dying within a year of each other. One of them spectacularly so, between the top of the couch where he was sleeping one night and the cushion onto which he fell dead between my parents while they were watching reruns of The Bill.

To stay working and living in Australia, Jessie is required to always be studying. Her parents’ money is helpful, though she is relentlessly bombarded with threats and bribes to come home. She’s almost thirty and they can’t see why she’d want to teach when her family leave her wealthy enough to do nothing. In between teaching six to ten piano prodigies a day, ranging in age from six to seventy-two (Antoinette, my mum, Antoinette, proudly claims to be Jessie’s oldest student), Jessie has finished a Bachelor of Music. She has learnt to be a Mandarin–Australian translator and now she’s onto a Masters of Education.

If Jessie’s not around, Mum and Dad will give me the latest update. ‘Erin, guess what happened to Jessie today?!’ they’ll offer as I plop down in their cluttered dining room. They’ll tell me about how they were able to explain some obscure Australianisms to her, express their distress at her experience of COVID-related racism.

As an adult I have moved further away from my parents. Not geographically; I’m still just three suburbs away. Emotionally though, I have a greater distance to travel now. For a long time, I didn’t feel accepted as a queer person by my parents and sensed they were ashamed of my masculinity, how I inhabited gender. I held ideas that if I was a ‘good enough’ child, I’d earn the love and acceptance I needed and wanted. I spent a lot of time trying to prove my worth. Making parts of myself smaller, inconsequential. I showed up and listened to my mother’s problems and worries in a way that as a therapist, I now know lacked boundaries.

My parents struggled, I think, with my identity, first out of a worry that life might be harder for me. For them, like many boomers, shaking the narratives that shaped the Catholic culture of their own upbringing was a task in and of itself; one I could see them continually reckon with. Their love was always there, I know this deeply now. I had no time, then, for their difficulty understanding me, and I didn’t give them a lot of room to have their struggles.

I wasn’t curious about where their lack of comprehension came from, or what might have been happening for them. I couldn’t consider at the time that they might have been doing the very best they could. I was dogmatic and reactive, hard and cutting.

My sister is Jessie’s age, thirty. For a number of years, during my sister’s late teens, my parents separated. I had already moved out, started haunting queer venues, found a ratty share house. My sister was volatile towards our parents, mostly verbally, but she was most spiteful towards our mum. Mum moved out. She left first to live in an over-55s community housing co-operative full of independent geriatrics. Later she skipped the state altogether and relocated to Tasmania to run the Older Person’s Unit at the Royal Hobart Hospital. I saw Dad siding with my sister and felt angry, as it signalled to me that the spiteful behaviour was permissible and that Mum didn’t matter.

I probably should not have done this, but, in an attempt to understand family patterns, I once wrote a 3000-word paper about my family for my Masters. I received my first high distinction. My own upbringing provided so many examples of systems gone awry, triangulation and confused family hierarchies. It was a dream case to review, albeit for a long time, a very difficult family to exist within. It was a no-brainer, to embellish that I’d met this family of four, de-identified of course, in my hospital emergency department, after the younger sister had plunged her arm through a window following an argument.

I studied how systems theory challenged the long-held pathologising psychological frameworks that came before and viewed families as existing within a network of interweaving generational family patterns, influenced by the larger social and cultural systems they occupy. It contends that problems aren’t just within the individual, but constructed socially, and encompass all the intersectional edges they touch: culture, race, gender, class etc.

A Real Piece of Work Erin Riley

An exhilarating, thought-provoking and joyful debut that asks how we create our identities and how we can transcend them.

Buy now