- Published: 3 October 2023

- ISBN: 9780143779773

- Imprint: Penguin Life

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $35.00

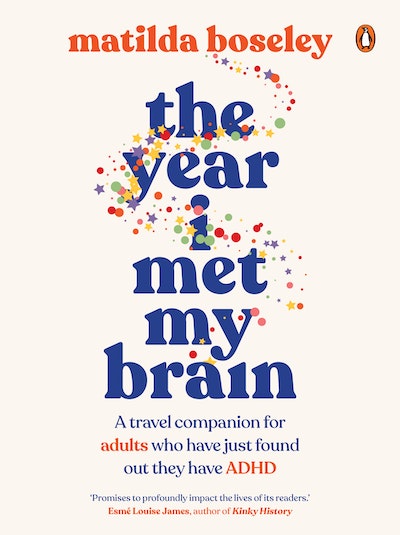

The Year I Met My Brain

A travel companion for adults who have just found out they have ADHD

Extract

I can’t exactly remember when I saw the first ADHD video, but it was titled something like ‘Five little-known signs of ADHD in women’, and I found it mildly interesting. When the video ended, I played it again and counted on my fingers all the things I related to, then hit the little heart-shaped ‘Like’ button at the side of the screen, saving the video in case I wanted to rewatch it later.

But this simple act must have alerted the AI overlords that I had at least a passing interest in the topic, so they shot a couple more ADHD videos my way. And just as predicted, I watched them, liked them and maybe even visited the creators’ pages to check out some more. This is gold for a company such as ByteDance, which owns the app – it had found a topic that kept me on its app and therefore kept me consuming its ads. So, like the dystopian megamind it is, the algorithm kept showing me more and more of these videos, desperate to extract every possible advertising cent my eyeballs could buy.

But as a side effect, my feed was suddenly filled with not just content about ADHD, but content made by women with ADHD, for women with ADHD. It was the first time in my life that I’d ever really considered that women could even have the condition, and, wow, a lot of the things they were talking about really did sound a lot like my anxiety.

After a few weeks, it began to dawn on me. I wasn’t only interested in these videos because it was cool to fall down a new internet rabbit hole. I was transfixed because the women on my phone were talking about me. It was as if they were reaching into my brain, pulling out everything that had ever made me feel weird and different but could never formulate into words, and listing them off in sixty seconds or less.

I know it’s corny to say, but watching these videos made me realise how lonely a little part of me had felt for all these years. Without even knowing it, I’d been keeping this secret shame tucked away, too scared to even admit there was something I was hiding. And here these people were, sharing it with hundreds of thousands, if not millions who all felt the same.

So I talked to my GP, who told me to talk to my psychologist, who, although surprised by my hypothesis, agreed there was probably something to it. She sent me back to my GP, who gave me a referral to a psychiatrist – and five months and $700 later I had my answer. TikTok was right.

Through some accidental quirk of late-stage capitalism, ByteDance had built a computer program that knew my brain better than I did. And I’m certainly not alone in this. Psychiatrists I’ve spoken to from all around the world have told me about the uptick of people, adult women in particular, talking to them about the videos they’d seen on TikTok and wondering if they might have ADHD.

An app that deals entirely in short, funny videos, delivering repeated bursts of immediate gratification, with an algorithm that has a knack of exposing undiagnosed people to educational content about ADHD, would be a game-changer in and of itself. But combine this with a global pandemic that utterly obliterates the concept of ‘normal’ for billions – toppling many people’s carefully built towers of routine, coping mechanisms and workarounds? Well, you’ve just created exactly the kind of environment that would trigger ADHDers who were missed in childhood to recognise that they need help and then seek a diagnosis.

It’s a big call, but I believe we’ll look back on the early years of the 2020s as one of the most pivotal moments in the history of ADHD, and one that fundamentally restructured the way our society thinks about neurodivergence in general.

I was the first person in my immediate circle to be diagnosed with ADHD, but I certainly wasn’t the last. Since then, every couple of months another one of my close friends or extended family or co-workers will mention that they’ve just received their diagnosis. And while this is extraordinarily brilliant news for them, I have to admit that a tiny part of me started to worry there was something in the water leaching all the dopamine from our brains, or maybe the critics were right: ADHD was just a ‘trendy diagnosis’ and we were all simply overreacting to not being able to sit through a TV show without being on our phones any more.

But neither of those options is correct. Population-wide prevalence has been remarkably steady for decades. So, really, it’s not so much that there are more people with ADHD nowadays but simply that more people know they have it. It’s just a pretty darn common disorder. I mean, about 2 per cent of children have red hair, which means – even by conservative estimates – a kid is three times more likely to be an ADHDer than to be a ginger.

The rise in diagnosis over the past decade, and even the somewhat sharper increase in adult referrals during the COVID era, aren’t some sign of the end of days or proof that ADHD isn’t real. Instead, this is a much-needed and long-overdue course correction based on decades of underdiagnosis and undertreatment. It’s good news! Sure, it might feel weird that you know 10 different people with ADHD, but it affects nearly 3 per cent of the adult population. I’m sure you know more than 300 people, so that’s just basic maths.

The Year I Met My Brain Matilda Boseley

An essential and empowering guide for any adult living with ADHD – compassionate, funny and full of practical tips. Shortlisted: Australian Book Industry Awards (Social Impact Book of the Year) Shortlisted: Australian Book Industry Awards (Illustrated Book of the Year) Longlisted: Indie Book Awards 2024 (Illustrated Non-fiction)

Buy now