- Published: 30 July 2018

- ISBN: 9780143782681

- Imprint: Hamish Hamilton

- Format: Hardback

- Pages: 224

- RRP: $29.99

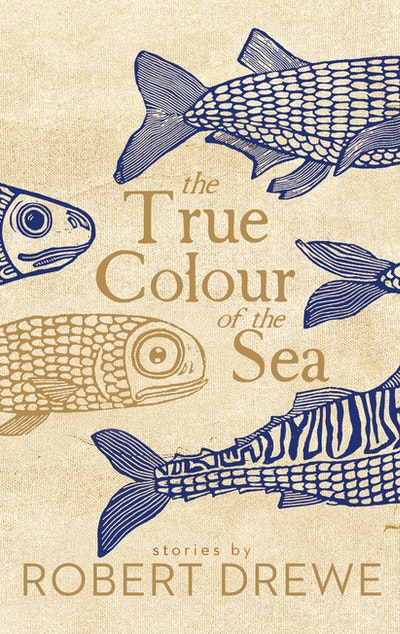

The True Colour of the Sea

Extract

Black Lake and Sugarcane Road

After I spotted a python climbing into her picnic basket and yelled out, I got chatting to a young woman down at Black Lake. She had a badly scarred face and a baby. She flipped one of her sandals at the snake, casually backhand, like she was throwing a frisbee; the snake uncoiled itself from the basket and slid up the nearest camphor laurel, and we got talking.

Diamond pythons aren’t venomous but it’s still a conversation starter to find one nestled in your sandwiches, near a newborn baby and all, and we went on to discuss local snakes in general, especially the number of dangerous eastern browns around this summer.

‘I hold the cane toad responsible,’ I told her. ‘It’s their fault the snake ratio is out of whack.’ I explained how before the toads migrated down here from Queensland, red-bellied black snakes used to keep the browns’ numbers down by eating their offspring. But not only did the toads get a taste for young black snakes, the adult blacks liked to eat cane toads, and then they died from the toads’ poison.

Sitting cross-legged on the grassy bank overlooking the lake, she seemed a typically serene Northern Rivers girl. Tumbling blond hair. Slender, tanned limbs. But under the hair her left cheek was shiny and crumpled like silver foil. The other side was pretty. While I tried not to stare at her scar, I outlined my theory and she nodded in an attentive way, brushed a bunch of hair aside and aimed the baby’s mouth at a breast. The fontanelle began pulsating gently and the baby’s ginger head fluff moved up and down as it nursed. It was a very new baby, still red and raw looking.

‘End result,’ I went on, ‘fewer black snakes – venomous, but relatively shy with humans – and many more browns – highly venomous and aggressive.’

‘That makes sense,’ she said.

After our lengthy snake talk we introduced ourselves and I said, ‘Do you mind,’ and I sat down on the bank as well. ‘I’ve been walking for two hours. Daily exercise.’

She said her name was Cynthia but she called herself China. ‘So you’ve been to China?’ I asked. ‘Or maybe you admire Chinese things?’

She said no and not particularly. When she was little her father had called her China, as in rhyming slang: China plate – mate.

‘We were very close, daddy and daughter. Then when I was twelve he went out for cigarettes one Saturday night, just like in a film, and never came back. He strolled off eating a Granny Smith apple.’

Ten years later she was working behind the bar in a Newcastle pub when her father came in. That was a shock. He saw her, downed his beer quickly and hurried off down Hunter Street. ‘I didn’t run after him. If that was his attitude, bugger him.’ Of course he had a drink problem. He was a country-town pharmacist who could never remember whether he’d made up a prescription correctly. He couldn’t trust himself and threw so much medicine down the sink that he went out of business.

China wasn’t at all self-conscious about her naked breasts but she slanted her head so the non-scarred side was facing me. She said her baby daughter’s name was Ayeshia, pronounced Asia, and she spelled it out. Keeping up the China connection, I guessed.

‘We live down there on Sugarcane Road,’ she told me, pointing south-west. Her partner Pete was part-managing a macadamia-nut farm for city investors: three Sydney surgeons needing a tax break. They didn’t necessarily want a profit and were embarrassed that the nut price was going gangbusters at present. The Asians loved them.

‘Pete’s definitely growing only maccas these days,’ she said firmly, switching the baby’s head to the other breast. ‘Not weed any more, not since the police crackdown.’

I said I’d heard of that. Helicopters and sniffer dogs, grumpy cops in riot gear tramping through the tropical rainforest, getting tangled up in the lawyer vines and spiky palms. Meanwhile bikers went unmolested and made ice in their backyard sheds.

She shook her head in wonderment and the scar glistened in the sunlight. ‘Even the old pot establishment that made this area what it was, the pre-hydroponic guys, are under threat these days. Even cop-friendly blokes – old drinking mates, top surfers and footballers – are being arrested.’

The far bank of the lake was quivering in a heat mirage over Sugarcane Road so you couldn’t tell where the lake ended and the cane fields began: a chequerboard plateau of sugarcane stretching to the horizon. An ibis stalked past and two purple swamp-hens scuttled along the shore.

‘Your Pete’s not being harassed then?’ I asked. A bit impertinent of me, but age allows you that sort of presumption. By now I was wishing a good life for this frank, scarred girl. And her baby daughter, born in the wrong climate for a redhead.

‘Not now. He did a lot of thinking and reading inside, and he’s more into the natural life than ever. He’s not a stoner any more, or a dealer. He’s so obsessive these days it’s not true, fighting the good fight against fluoridation of the water supply and child vaccinations, anything governmental. Every weekend he’s out poisoning camphor laurels. You know that camphors are feral weeds that poison rivers and kill wildlife? Not to mention being bad for humans. They’re not native Australian trees – they were introduced from Asia.’

‘From China. And we’re sitting in the shade of one now.’

She let that go. ‘The camphors are the toxic enemy that Pete’s sworn to eliminate. He says they even encourage drug use.’ A flicker of irony showed on her face. ‘Their thick canopies hide the crops from the police choppers.’

‘He must have his work cut out.’ The Northern Rivers landscape is enveloped and softened by millions of camphor laurels. Everywhere, the attractive rounded trees moderate the scenery. From the air the ground looks like the green European countryside of the model railway I had as a kid. At ground level the trees remind me of big bunches of broccoli. The camphors thrive where the cedar cutters and cattlemen razed the rainforest known as the Big Scrub in the nineteenth century. Farmers hate them because they shoot up everywhere. The hippies hate them because they’re not native vegetation. They’re ideologically unsound and not your noble Aussie eucalypts. Farmers and Greens in cahoots against a common enemy – a tree. That’s one for the books.

While we watched a cormorant choking on an eel, I thought about little Ayeshia, still guzzling away on the breast. And of rubella, polio, meningococcal and tetanus, too, not to mention measles, mumps, whooping cough and diphtheria and the free government vaccinations that could prevent kids from catching them these days. And the daughter Margie and I lost to meningitis in 1984 – Emily. And then Margie going suddenly three months ago.

I’d never sleep if I didn’t walk every day to tire myself out, to slow down the adrenaline. Around the lake takes me two hours at medium pace, then I dive in to cool off.

The cormorant gagged for about five minutes but eventually got the eel down. I was surprised the bird could even see an eel in Black Lake. Tea-trees dip into the lake and leach their tannin into the water. In the shallows it’s yellow and warm and disconcertingly piss-coloured, but as you wade out the water turns orange, then quickly reddens to a deep burgundy. Dark as a blood test.

Twenty metres from shore the redness darkens to pitch black. By the time you’re waist-deep you can’t see the bottom. Then the lake bed falls sharply away. Who knows how deep the lake is now? The water temperature is layered, warmish for a metre or so down, then suddenly cold. Swimming overarm feels threatening if you have your eyes open. I swim backstroke so I don’t have the sensation of swimming into an abyss. If you were drowning or slipped under on purpose your body would be hard to find. I’ve occasionally given it some thought.

Strange how this weird soft water doesn’t sting your eyes, and your skin feels smooth when you get out. Then you forget what it was like out in the deep. How pessimistic it made you feel.

A dusty white Toyota HiLux pulled up sharply then, and a burly red-bearded fellow got out and strode over. He wore a black cap with a motor-oil logo and sunglasses perched on top of it. ‘There you are!’ he said, half-smiling and frowning simultaneously, and squatted down beside us. ‘It’s getting bloody late, China. I wondered where you’d got to. Off with one of the old boyfriends maybe.’

‘Sorry, babe. I took Ayeshia for a walk to the lake and this gentleman saved us from a diamond python.’

I’m not sure I like younger people nowadays referring me to as a gentleman or sir. It’s all to do with age. Until I was fifty I wasn’t sir. I was mate. On that subject, I was surprised now at Pete’s age. He had twenty or twenty-five years on China. There was grey in the red beard. We shook hands. He applied pressure. Not a particularly friendly handshake.

‘Pythons are fucking harmless,’ Pete scoffed. ‘Unless you’re a rat or a rabbit. Or the family cat. Jesus, I thought everyone knew that.’

‘I know, babe. I was joking. The snake crawled into our basket so I scared it up that tree.’

He glared at the tree for a long moment, went to his truck, and returned with a poster and a staple gun. He nailed the poster to the tree: a skull and crossbones and a scarlet slogan. Stop the Camphor Menace.

‘I’ll come back later for that one,’ he said.

‘China says the tree-poisoning keeps you pretty busy,’ I said to him. ‘How do you go about it?’

He frowned at me, then her, and didn’t speak for some seconds. Then he focused his eyes on me. A fierce faded blue. He blinked.

‘To answer your question, it depends on the site, tree size, access and your personal herbicide preference. There’s various methods – cut stump, stem injection, basal bark or foliar spray techniques. All legal herbicides available to any weekend gardener. Glyphosate 360, picloram 100, triclopyr 300. Just doing my bit to disrupt plant cell growth. Someone has to, when the government does bugger all.

He turned abruptly from me to China. ‘Fun’s over. Time to go. I’m fucking hungry.’ He stomped ahead to the truck.

The sun was above the far cane fields. Still about an hour from setting. As she packed up the baby and the basket, China murmured, ‘He likes to eat early, drink a bit and hit the sack.’

Then she said, ‘You were wondering about my scar?’

Of course I had been, amongst other things. Like life in Sugarcane Road. But I muttered, ‘Not at all. I’m sorry I’ve kept you.’

‘It’s OK,’ she said, and touched my arm. ‘Actually, it wasn’t him that time. It was one of my exes.’

The True Colour of the Sea Robert Drewe

The long-awaited new collection of short stories from Australia’s master of the short-story genre.

Buy now