- Published: 15 August 2023

- ISBN: 9781761047572

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 368

- RRP: $19.99

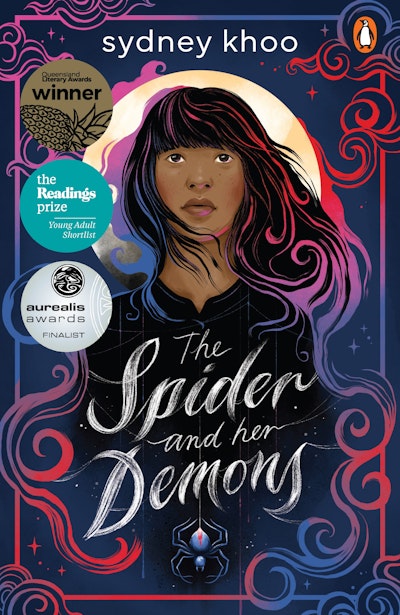

The Spider and Her Demons

Extract

Aunt Mei is up early every morning so she has enough time to prep for the lunch rush, and Zhi’s first job when she gets off school is to prep for the dinner rush. Between waiting tables and cleaning, she’s folding. A spoonful of filling, wrapped in skin and folded, on a tray of ready-to-cook babies, placed in the fridge, awaiting the steamer or pan.

It’s second nature, and one of the less frustrating parts of her job.

‘Did you know you’re missing numbers on the menu?’

Zhi tries not to sigh. Tries not to beg her soul to leave her body so she may spiritually depart from this world. Instead she nods, pasting on a smile. Before she can open her mouth, the customer continues –

‘It goes straight from number three to number five, and then it goes from number thirteen to number fifteen.’ The customer cackles. ‘Whoever did the sign needs to be sacked!’

‘Oh, honey, don’t be like that. Maybe they didn’t know.’

‘Didn’t know the number four comes after the number three? I’m doing them a favour, then, teaching them basic maths.’

‘They’re supposed to be good at that kind of thing. I’m sure one of them noticed.’

Zhi’s eye twitches. ‘Sorry, were you ready to order? Because I can come back.’

‘Are you sure you can’t make tonkotsu ramen and gyoza? It’s pork soup with noodles. I used to eat it in Tokyo all the time when I worked there.’

‘Yeah, I’m sure that was a great learning experience for you,’ Zhi says. ‘But we’re a Chinese restaurant.’ She points her pen at the sign on the back wall that reads THE DUMPLING PALACE in both English and Chinese. ‘We have egg noodle soup, and pork and chive dumplings, if you want. That’s the closest thing you’re gonna get here.’

The couple stare at her.

‘Honey, maybe we should just go to that place by the bookstore. They have those crunchy fish-balls you like.’

‘It’s a twenty-minute walk, and it’s hot out.’

It is hot out. The bus back from school was packed and the air-conditioning was broken, so Zhi was a melting sardine stuffed in a tin can of other melting sardines, stuffed in the oven that’s Sydney CBD. When she got home, she had to peel her school uniform off and bully her way into her restaurant uniform. Her fringe might be bulletproof but it isn’t sweat-proof – and it’s currently clumping together underneath her kitchen bandana.

‘There’s nothing you can do? We wanted something really . . . really authentic.’

Zhi’s not sure how else to make Chinese food, cooked by a Chinese chef, served by Chinese staff in a Chinese-owned restaurant, any more authentic than it already is. She’s about to tell them so, when Aunt Mei comes around the table, squeezing herself in between Zhi and the customers.

‘If you want something really authentic, you have to try the qing tong mein with gao choi gau.’ Aunt Mei points to the menu on the right side of the counter, a long numbered list of Chinese characters that Zhi can’t read. ‘Only other Chinese people order this.’

‘Ooh, what is that?’

‘A very special, very traditional dish.’

‘Yes, hon, let’s try that.’

‘What else? What else is really authentic?’

‘The sambal kacang goreng. Very popular Malaysian dish. We eat this all the time back home.’

Zhi’s gotta give it to her; it’s not a lie. They regularly eat restaurant leftovers at home. They don’t have energy to cook a proper dinner after they finish work, so they often cook up whatever hasn’t been ordered by the end of the night. Leftovers from those leftovers become their lunch the next day.

On rare occasions, when Aunt Mei isn’t too tired, she’ll whip up something special. Sometimes it’ll be a dish she learned to cook back home, from her ah ma or her maa maa. Haam choy tong. Assam laksa. Hoi naam gei faan.

But most of the time, she’ll cincai jyu. A tin of Spam, cut into thin slices, microwaved. Lettuce ripped into bite-sized pieces, left to go limp in a pan with oyster sauce. Zhi wonders if either of those dishes would qualify as authentic.

‘It’s so nice you run this place with your daughter.’

‘Ah, thank you. This is my niece.’

‘Really? You look so much alike.’

‘Her mouth is much bigger than mine,’ Aunt Mei whispers loudly. It’s nothing Zhi hasn’t heard before, so it shouldn’t annoy her.

The Authentic Couple laughing at it though, that has Zhi heading off to the kitchen. Before she’s managed to get to the door, it opens in her face, and she almost knocks a plate of dumplings to the ground.

‘Aye, you ’right?’

‘Tobi,’ Zhi breathes. ‘Please, please use the window for food.’

Tobi looks down at the dumplings she’s holding, then over to the service window next to the door.

‘Oops, yeah. Soz. I forgot,’ Tobi says, sheepishly. ‘I got excited. Nicky said this one was ready!’

Tobi’s been The Dumpling Palace’s delivery driver slash waitstaff for just under a year. She doesn’t mind making deliveries, which is a godsend since they can’t afford the thirty percent cut the delivery services take. But she’s really upbeat, which Zhi doesn’t get. They work in customer service – what’s there to be upbeat about?

Nicky rings the bell. Tobi peers at the two extra plates of dumplings that have appeared on the bottom shelf, then back down at the plate already in her hands.

‘I’ve got it,’ Zhi says, taking the plate from her.

‘I still dunno how you juggle three. I’ve been practising, but.’

‘It’s all in the forearm,’ Zhi says, stacking the plates carefully. ‘Probably helps that I’ve been doing this a lot longer than you.’

‘Oh yeah! You’re a proper profesh. A seasoned waiter.’

She doesn’t know if she’d call herself a seasoned waiter.

She’s been working here since she was, what, five? But she only started doing waitstaff duties after Mr Chin sold Aunt Mei the business. When was that? Around Year 3?

Which means it’s been . . . roughly seven years?

Zhi carries the dishes over to their tables, schooling her face into a pleasant smile. Maybe she is a seasoned waiter.

Wednesday nights at the restaurants aren’t so bad. Thursdays, all the late-night shoppers stay out till ten, cramming shopping bags under their tables as they wolf down their meal. Fridays, they’re swamped with business workers celebrating the end of the week, asking non-stop if they serve alcohol. Saturdays are busy from opening to close. Sundays, takeaway and deliveries are at an all-time high.

This early in the week, it’s easy. Quiet. Bad for business, but good for Zhi. It means she can work on her Visual Arts proposal between serving and cleaning. At the rate she’s going, she might even be able to get into bed early.

‘Tobi’s had an accident.’

Zhi looks over from where she’s wiping the table by the window. Aunt Mei slams the phone into its cradle a little too hard, muttering to herself in Cantonese. She squints at her laptop, glasses perched on top of her head.

‘What happened? Where is she?’ Zhi asks. She heads over, pushing the glasses down Aunt Mei’s face, but her frown doesn’t budge. ‘Is she coming back to the shop?’

‘She’s on her way to Royal Prince Alfred.’

‘She’s going to hospital?’

‘She said it’s not bad.’

‘Yeah but–’

‘The scooter is a write-off.’ Aunt Mei’s voice is loud, and Zhi flinches from it.

Nicky looks between them, sliding a plate of dumplings through the window and hesitantly tapping the bell.

‘I’ve got it,’ Zhi says, quietly.

Last year, Aunt Mei asked Zhi whether she thought the motor scooter would be worth insuring. They’d had it for a few years already, second-hand, and it was quite literally falling apart: bumper missing, side mirrors secured with duct tape. It was difficult to lift the seat off to store anything in, so they generally pretended it had no boot.

They calculated the cost of insuring it was about the same as buying a replacement if anything ever happened.

‘We’ll put the money we save aside,’ Zhi said to Aunt Mei. ‘So if anything happens to it, we’ve got that as back up.’

But then the exhaust hood collapsed in August, and in November the customer toilet wouldn’t flush and they had to pay a plumber to come out. Running a restaurant is expensive, and they barely make enough to cover Zhi’s school fees.

All at once, Zhi feels guilty.

‘We should cancel maths tutoring,’ Zhi says. ‘It’s fifty bucks a week we could save.’

‘What did you get on your last test?’ Aunt Mei reminds her sharply.

Zhi looks away. She got a seventy-eight, which is practically a fail in Aunt Mei’s books. And that was with two hours of tutoring a week.

‘If you studied harder, you wouldn’t need a tutor. Wasting all that time on your phone.’ Aunt Mei slams the laptop shut, going back into the kitchen, the door swinging behind her.

Zhi takes in a slow breath through her nose, then exhales out her mouth.

‘Yeah,’ she mutters. ‘I know.’

Zhi takes the laptop over to an empty table, lifting the lid. The house budget spreadsheet is open. Aunt Mei was probably checking if they had any spare funds to pay for a new scooter. Without it, the shop won’t be able to make deliveries.

Worse comes to worst, maybe they can use the van for a few weeks. The petrol costs will be higher, but there’s not much they can do. Zhi’s pretty sure Tobi has a car licence. People with a motorbike licence usually have a car licence too, right?

It probably all depends on how bad Tobi’s injuries are.

The restaurant phone rings. Aunt Mei rushes out of the kitchen, answering with a stern, ‘Dumpling Palace.’ Her eyebrows furrow, and she starts nodding to herself. ‘Yes, okay. Yes, no problem. Yes, thank you.’

Zhi frowns, watching Aunt Mei hang up the phone.

‘Was that Tobi?’

‘Go get the bike from upstairs.’

‘Is she okay?’ The words take a moment to process. ‘Wait, what bike?’

‘The bike from upstairs.’

Upstairs? Zhi wracks her brain. ‘You mean the bicycle? The bicycle behind the TV in the lounge? Why?’

‘Why do you think?’

Zhi stares at Aunt Mei, who has just finished scribbling into her order notepad. She rips out the page and passes it to Nicky through the window.

‘Did you just take a delivery order?’ Zhi asks, bewildered. ‘We don’t have a driver.’

‘You can cycle, can’t you?’

Asking Zhi to get the bike from upstairs suddenly makes too much sense. ‘Kuku, no. Just tell them our driver’s been in an accident.’

‘It’s The Big Dipper,’ Aunt Mei says, like that’s supposed to change Zhi’s mind.

‘It’s past eight,’ Zhi says, trying not to sound whiny. ‘I’m exhausted. Can’t you take the van?’

‘Van costs petrol. Bicycle is free,’ Aunt Mei says, like it’s that simple. ‘The helmet is in the storeroom.’

‘Kuku–’

‘We need the money.’ That effectively shuts Zhi up. ‘Faai ti zhou la.’

Zhi goes.

‘Wait,’ Aunt Mei calls.

She sags in relief, turning, only to see Aunt Mei holding a fat wad of takeaway menus.

‘Bring these with you.’

‘The Big Dipper does not need thirty copies of our menu. They always order the same thing.’

‘For you to put in the houses.’

Zhi can’t believe this. She wants to say, I’m not doing a leaflet drop at eight pm on a Wednesday night, but it’d only start a fight. ‘If I have time, sure.’

‘Okay, zhou la, zhou la.’

Zhi goes.

The helmet is tiny. Easily a size too small for Zhi’s head, it’s covered in Peppa Pig stickers and wobbly lines of purple glitter. It says Darceigh across the top in faded Sharpie. A customer must’ve left it at the restaurant and forgotten to come back for it.

It’s a thirty-minute bike ride, which wouldn’t be too bad, if she wasn’t trekking uphill all the way.

‘In two hundred metres, turn right onto New South Head Road,’ her phone says through her earphones.

Daylight savings hasn’t flipped yet, so it’s not completely dark out, despite being so late. Though it’s well past peak hour, traffic is still pretty heavy, cars backed up all along the main road. Zhi hates to admit it but Aunt Mei made the right call sending Zhi by bike.

She’s just turning onto Warrawal Road, riding along the long stretch of it, when the air turns cool, a blissful breeze from the harbour hitting the boiling skin of her cheeks. Sydney’s sticky summer always lingers past its welcome, but evidently it’s not so bad on this side of the city.

The houses on this street are generously spaced, each one looming tall and intimidating. They’re all mini-mansions, with multi-car garages, and tall security gates.

‘In four hundred metres, your destination will be on your left.’

Zhi rides past her destination before circling back, pulling up on the other side of the road. She parks the bike under a flickering street light, shoving her phone in her pocket.

Beyond the overreaching black metal fence out front of 48 Warrawal Road is a deep-mustard, double-storey manor-like house. Zhi’s never been to Europe, but she can totally imagine a place like this in the middle of Tuscany or something.

This close to the harbour, there’s probably a waterfront view on the other side of the property.

Of course The Big Dipper lives here.

The gates are open, so she forgoes the intercom and strolls straight through, up the steps and to the front door. She can’t find a doorbell, so she knocks a couple of times – then, annoyingly, spots the doorbell on the side. She pushes it once, hearing the classic ding-dong sound from inside.

There’s some shuffling before the door pulls open, light spilling out onto the entrance. Zhi takes a couple of steps back, unzipping the delivery bag.

‘I’ve got an order from The Dumpling . . . Palace . . .’ Zhi trails off, face burning hot as The Big Dipper steps out the front door.

Barefoot, toenails painted purple and gold, in three-quarter tights that sit just below a pierced belly button, and a white crop top that criss-crosses over the waist, oversized fleece jacket hanging off one shoulder, chunky headphones around a long neck, curls tucked behind one ear, showing off a dainty gold hoop.

Dior Panne-Nix.

‘Hi,’ she says, smiling prettily. ‘Do I know you?’

Zhi stares. She’s got to be–

‘Joking.’ Dior’s smile falls off her face. ‘That was a joke.’

Honestly, it would’ve been better if Dior didn’t remember her. Zhi’s in the restaurant uniform – black button up, black slacks and black canvas shoes. Her sweaty hair has clumped against her forehead under the kitchen bandana. She’s realising with a dousing horror that she’s still wearing the Peppa Pig helmet.

Hurriedly, she unbuckles it, adjusting her bandana across her forehead when it slips. As if today hadn’t been bad enough, the universe had to kick her while she was down.

This is what she’s going to think about when she tries to fall asleep at night. When she’s thirty-two and working a nine-to-five, this is what she’ll think about on the train ride to work. When she’s forty-eight and wondering where her life went wrong, she’ll think of this. When she’s on her deathbed, pondering on all her regrets, this will be the moment that presents itself. Looking greasy and disgusting in a child’s helmet in front of the most stunning girl in school.

‘You work at The Dumpling Palace,’ Dior says.

It’s not a question, but Zhi nods. ‘Uh, yeah. It’s my aunt’s restaurant.’ She pulls the paper bag out, holding it out by the cardboard straps. ‘Um, two servings of pork and chive dumplings, right? One steamed, one pan-fried.’

‘Thanks.’ Dior takes the food in one hand, holding out a hundred-dollar bill in the other.

Zhi’s never seen a hundred-dollar bill in real life before, let alone touched one. She takes it with both hands, holding it up to the light. Turns out it’s exactly like any other plastic bill, only green.

The issue is, Zhi absolutely did not bring enough change for this transaction. She digs into her pockets, but all she’s got is a ten, a twenty, plus a couple of coins.

‘Oh, you can keep the change.’ Dior waves her off, like tipping someone more than double the cost of their food is normal.

No wonder Tobi and Aunt Mei call her The Big Dipper.

Well – Tobi referred to a customer as a big tipper and Aunt Mei started calling them The Big Dipper, no matter how many times anyone corrected her. Zhi had no idea it was Dior Panne-Nix who’d been ordering from them all this time.

‘Did you want to come in?’ Dior asks, leaning against the doorframe. ‘My parents aren’t home.’

Zhi lets out a laugh of disbelief, then immediately presses her lips together.

That was rude, probably. Definitely.

But surely Dior has better things to do than sit around eating takeaway with a delivery driver (or a delivery cyclist, in this case). Surely Dior has some super shiny supermodel, semi-celebrity friends she could hang out with instead?

What would they even talk about if they hung out? Zhi knows nothing about what it’s like to be rich and beautiful. It smells like a prank, if she’s honest. Lure Zhi into a house filled with other popular girls dressed like . . . like Dior’s dressed, only for them to pull out their phones and laugh at her. She’ll be on the WAC app by tomorrow morning.

Dior must mistake Zhi’s hesitation for consideration, because she smiles, this bright and hopeful thing.

‘Maybe some other time,’ Zhi says, not meaning it at all. ‘I’ll, uh, see you at school?’

The smile drops from Dior’s face.

‘Sure,’ Dior says, coolly. ‘See you.’

She doesn’t exactly shut the door in Zhi’s face, but it’s a close thing.

Zhi pops one earphone back in, heading down the steps, helmet tucked under an arm. She pulls her kitchen bandana off, shaking her fringe out, peeling the tape off her extra eyes and blinking through the clumps at the quiet of Warrawal Road. The streets here are so much wider than the city. There are a few cars parked on each side, and there’s still ample space for other cars to drive through.

Pulling her phone out, Zhi inhales the night air, stepping off Dior’s property and onto the road. She’s busy trying to think of how she’s going to word all this in the group chat, when she bumps into something big, hard and very much alive.

‘Oops, sorry,’ she says, on reflex, looking up.

Her sweat turns cold, the warmth of her skin snuffed out.

A stranger smiles down at her through a thick beard, mouth opening into a gruff laugh, spilling rotting breath into the space between them. Zhi takes a fumbled step back, flinching when hands grab at her shoulders, keeping her still.

‘You should watch where you’re going, sweetheart.’

Zhi tries to jerk away, but she’s being gripped so fiercely, blunt fingers clamping into her flesh. Zhi’s only small. It wouldn’t take much for someone of this size to crush her.

She wonders if she should scream, if someone would hear her, or come running out of their billion-dollar house to help her, even if they did.

Then she wonders if she should do anything at all.

Suddenly she’s five years old, Aunt Mei’s hands on both her shoulders, digging fingers into Zhi the way this stranger is right now.

Be small. Be quiet. Be invisible.

‘Hey, Rook, look what I found.’ Zhi’s spun around, a huge hand splaying across her neck.

There’s two of them.

The other one is slighter, with pale skin and thin hair, blue-blue eyes glancing away from the houses to settle on Zhi.

‘That’s not what we’re here for. Can we just get this over with?’

Rough fingers tug Zhi’s head to the side by her hair. Zhi flinches as the tip of a nose hits the back of her ear. A noisy snuffle has her breath stalling in her lungs.

Is . . . Is she being smelled?

A storm of static fills the space between her ears, until it overflows, trickling cold down her spine, leaking into her bloodstream, until she’s frozen all over.

‘What do you think?’ A palm strokes down Zhi’s arm, gripping her wrist, thumb rubbing the delicate skin there, and if she had any room inside her body to feel disgust, she would. ‘Do you wanna have some fun with us?’

‘I’m sorry about him,’ the other voice says. ‘Leave it, Brig. We don’t have time for this.’

‘Aww, he’s no fun, is he?’ the larger one growls. Zhi feels it through her back, the rumbling passing from his flesh into hers. She’s half-aware her body’s shaking, hands squeezing the front of her shirt in an effort to keep herself still. ‘I guess, it’s just you and me, sweetheart. I’ll make it quick.’

Zhi remembers, quite uselessly, that Aunt Mei has warned her, all her life, there are fates worse than death.

The fear in her body peaks, a wave at its crest.

Zhi has no other choice but to surrender to it – water crashing into her skin, drenching her, and pulling her down into the sea.

She lets herself drown.

Zhi thumps her head back against the body behind her. Without the eye tape, without her bandana, without her helmet, between the clumps of her fringe, she looks up with all eight of her eyes.

She can make out every pore, every hair, every curl of flaking skin. She watches the shifting of dilated pupils to meet her gaze.

If Zhi survives this, she will remember every detail.

She will never forget.

Green eyes enlarge in slow motion, skin stretching, whites widening. The hand on her throat goes to her chin, jerking her head further back. Her human eyes stay on his face but her extra eyes stray to his neck, to that soft spot where his carotid artery is pulsating, blood pumping fast.

It suddenly occurs to her that she’s starving.

‘You–’ He releases her, hands shoving Zhi off him. Her back is cold without the body crowded against it. ‘You’re–’

Her legs are peeling through her skin before she can stop them, the hem of her shirt slipping out from her trousers as her hind legs creep out the back of her shirt. Both upper

paws grab a thick shoulder each, clenching tight, and it’s funny, hysterical even, that he should scream; Zhi was so quiet when it happened to her.

She’s crawling up his body in an instant, around his waist, his back, a paw gripping his hair and yanking his head to the side, fangs piercing through her gums.

Zhi’s eyes meet blue-blue, and she bites down into a thick neck, mouth filling with blood, acid and venom pumping into the wound.

She feels the jaw in her palm drop into a scream, but there’s no noise.

Just blissful silence.

The body beneath begins to go limp, teetering. Zhi sucks once more, hard, before unclamping her bite, and even that, she does perfectly, not a drop of blood spilling.

‘G– Get off– Don’t touch him! Get away from him!’ the smaller one squeaks.

Zhi climbs down, human feet hitting the ground. Her hind legs catch the body as it falls, flipping it onto its side, abdomen throbbing as she wraps it in silk.

In her periphery, she spots movement. She drops her head back as far as it can go, watching upside-down as the other stranger scrambles across the road. Zhi can see the tremble in his movements, the way his eyes dart side to side.

Her stomach snarls, hunger clawing at its walls. She looks back to the feast in front of her, cooking in its cosy cocoon. She doesn’t even need to squeeze or prod at it to know when it’s ready; her body moves on its own, biting into the sack and sucking out the innards.

It splashes hot and thick on her tongue, and she swallows it down in long pulls, throat stretching to accommodate.

A rich stew cooked into liquid gold.

She feels the eyes on her forehead roll back, lids fluttering closed. With her human eyes, she vaguely acknowledges the stranger circling her, but it’s hard to bring herself to care.

There’s no danger here.

Her stomach fills with warm euphoria. She can’t figure out, can’t remember, why she’s gone all her life without this.

It’s only when there’s nothing left to swallow, no meat left in the sack, that it comes trickling back – all the reasons why killing someone and eating them is Not Good.

It’s as though she’s been dragged from a dream that insists on lingering. There’s a low pleasant hum under her skin, tingling all throughout her body, entirely discordant to the thunderous roaring in her head.

Zhi stares, and stares. At the scrap of white gunk in her paws – the only remnants of what was, moments ago, an entire human being. Clothes, skin, flesh, bones, dissolved by her acid.

‘Oh my god.’

She’s just killed someone.

‘Oh my god.’

This is not one of those mistakes she can fix. She can’t CTRL + Z this. No amount of studying or tutoring is going to bring a human being back to life.

He was creepy. He was scary. But Zhi didn’t have the right to melt him into goo and chug him like a can of soup.

Down the road, a car turns onto the street, headlights beaming. Zhi scuttles into the shadows, breathing hard as she tucks her form away, dropping the ball of silk into one human hand. With her free hand, she tugs her shirt down where it’s ridden up, tucking it into her pants. She combs out her clumped fringe as best she can, digging her bandana out of her pocket and pulling it over her forehead.

When she squints up the road again, the car has pulled into one of the houses down the way, not even coming close.

Zhi exhales slowly.

Now is not the time to fall apart.

She looks around for the other one, the one with the blue-blue eyes, but he’s gone.

As is her bike.

Her helmet is in the middle of the road, along with her phone, earphones, the delivery bag, and a puddle of . . .

Zhi grimaces as she steps closer, the stench pungent and impossible to mistake for anything else.

Urine.

Zhi shoves the ball of silk inside the delivery bag, clipping the helmet over her head. She can’t seem to steady her breath, and the warmth in her stomach has percolated into nausea. It’s bad enough, what she’s done, but someone’s seen her do it.

If she ran now, she might be able to find him. There’re only two directions he could’ve gone.

But – If she catches up to him, then what? What is she going to do? Kill and eat him too?

The roaring in her head gets louder, until her temples pound with it. She scrubs a hand over her face, consciously inhaling slow.

If he calls the police, it’ll be a while till they get here, even in such a fancy suburb. What’s he going to say to them anyway? My mate was just eaten by a small Asian girl who turned into a monster? Who’s going to believe him?

Zhi just has to stay out of sight. He doesn’t know her name. He doesn’t know who she is or where she lives. He knows nothing about her.

She’s entirely forgettable. She’s nobody. It’s fine. It’s fine.

Everything is fine.

All she has to do is get back to the restaurant. She’ll tell Aunt Mei someone stole the bike – which is true – but she’s still got the money, so there’s no worries. No sweat. All good.

She picks her phone up off the ground. Miraculously, it’s not cracked – though the cord of her earphones is torn half off. When she starts the route guidance, no sound comes out. She’s turning on the spot, trying to get the compass on her maps app to sync, when her gaze catches on the yellow light across the road.

Standing by the front door of 48 Warrawal Road, is Dior Panne-Nix.

Zhi blinks.

Slowly, Dior raises the bag of food in her hand.

‘You forgot the dipping sauce.’

The Spider and Her Demons sydney khoo

Uncover an extraordinary world of demons and witches, where the ones you love can hurt you the most and hiding your true self can get you killed. Winner of the Queensland Literary Awards, Young Adult category, shortlisted for the Readings Young Adult Prize and a finalist in the Aurealis Awards.

Buy now