- Published: 21 April 2020

- ISBN: 9781760899868

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $24.99

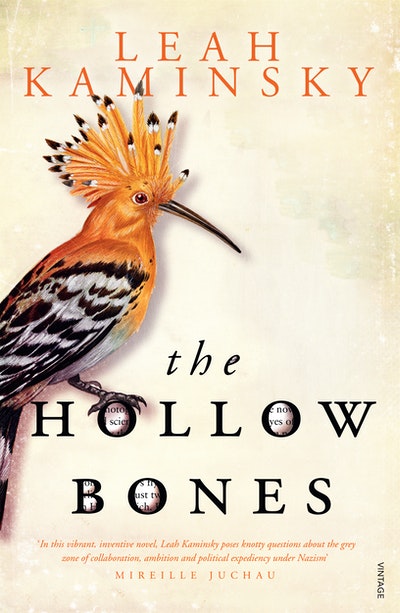

The Hollow Bones

Extract

As you prepare to leave the world you were so hungry to explore, I imagine I can see a tinge of regret in your eyes and I wonder how we both became the people we are. History unfolded in ways we never could have dreamt of when we were children growing up in our pretty town. Who might we have been had we met in a different place, or another time, citizens of a land far away from our own sullied, shadowy one?

As I watch you sleep restlessly, your wrinkled hand against the white sheet, I am conjuring up our impossible reunion, pretending I am standing at the entrance to 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, under the wings of the bronze angel silhouetted against the sunlight as it lifts a dead soldier out of the flames of war. I see your familiar figure walk towards me through the throngs of passengers jostling to board their trains. You carry the leather travelling case embossed with your initials that I gave you on our tenth wedding anniversary. We embrace, and lips meet, our love made inconspicuous as it is swallowed by the crowd.

At our house on the edge of the park, I picture the children awaiting your return. Little Heidi is fluent in three languages and plays the flute, all of my abandoned dreams re-emerging when I see her small fingers positioned above the keys. How long it has been since I held a flute in my hands. Our Brooke is captain of the school archery team. His father’s son. You are a professor of ornithology, specialising in rare Tibetan birds, and I sometimes slip into the crowded lecture theatre to watch you standing at the podium, spinning your exotic tales to another crop of enthralled students. You are filled with knowledge about birds: the iridescence of feathers, the wizardry of flight, the vagaries of their migrations. We spend our summers on Campobello Island with the Roosevelt clan and send money home to our families to help them rebuild their lives.

On the bed by the window you stir, and your once strong fist claws at the sheet as you struggle to breathe. Soon we will both disappear forever, our story hidden away in dusty archives. Gone will be those children who followed a slender path to their hideaway in the woods, gone will be the lovers who kissed on that fateful day at the zoo. I want to forget the darkness and remember only the good; illusion is such a temptress. It won’t be long before we will both float weightlessly, unmoored, our bones hollow like the birds’. I remember you once told me about mockingbirds and their special talents for mimicry. They steal the songs from others, you said. I want to ask you this: how were our own songs stolen from us, the notes dispersed, while our faces were turned away?

CHAPTER 1

18 June 1936

‘The Reich needs young men like you.’ The balding officer seated across the desk peered at Ernst through round spectacles, tiny eyes gleaming like those of a crow that has caught its morning worm.

Ernst wriggled in his seat, smoothing down his froth of sandy-blond hair, uncertain whether a smile was appropriate under the circumstances. The office at Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse 8, the site of a former baroque palace, looked austerely furnished. On the desk were a brass lamp and a neat pile of papers, with fountain pens lined up in a row like soldiers at a drill.

‘I am so glad you have returned home, my boy. I shall be very pleased to be your mentor. After all, I am a great patron of the sciences,’ he cawed, in a pantomime of exaggerated politeness. ‘And I am a collector, too.’

‘It is both my duty and a great honour to serve the Fatherland, Reichsführer Himmler.’ Ernst fidgeted with his collar as he recited the expected response.

His myopic superior grinned.

Ernst scanned the room. It seemed Himmler was indeed an eclectic hobbyist. On a side table sat an antique orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system. Bookshelves sagged under the weight of books on subjects ranging from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita to the lost city of Atlantis. Jars of homeopathic remedies, with long Latin names inscribed in ink on their labels, served as bookends. Ernst had heard the man’s tastes were rather unusual, but the breadth of his interests proved far more than Ernst had bargained for – from telepathy to the sexual habits of Tibetan tribes, heraldry, reincarnation, astrological signs and ancient runes.

‘Do you know why I brought you back?’ Himmler brought an unlit pipe to his lips, pretending to puff on it. ‘I need you to help me add to my collection.’

‘Pardon, Herr Kommandant? I’m not sure I understand.’

‘I have been following your recent expeditions to China and Tibet, with that young American adventurer – what was his name?’

‘Brooke Dolan, Herr Kommandant.’

‘Yes, Dolan – I have been watching with a great deal of interest.’

‘Thank you, Herr Kommandant.’

‘You were wasted over there in America. I have received correspondence from Fritz Kuhn of the German American Bund informing me of the mood in the United States. We certainly don’t need those Americans for our own expeditions; neither their Jewish vermin nor their money. We can do it all ourselves, and far better.’

Ernst waited cautiously to see if a response was called for.

Himmler watched him. ‘I have chosen you, Schäfer, because of your experience in the East.’

Ernst was sweating; the room had no fan, and the day’s heat was starting to rise. To get to the meeting on time, he had needed to be on the platform at the Zoo station by 8.30 am to catch the S-Bahn to Potsdamer Platz. Though the city was running like clockwork for the forthcoming Olympics, Ernst had become accustomed to keeping his own schedule, punctuality never his greatest attribute. All those months travelling in the East had dampened his sense of schedule and order. There was no way a porter or his mule could be trained to work to anyone’s timetable without being whipped, and he was not stupid enough to abuse those he needed the most. On those misty mornings, camped along the banks of the Yangtze, serenaded by songbirds while yak tea brewed on the campfire, his life had been veiled with a sense of timelessness. Wearing a uniform of dungarees and waterproof jacket, his trusty shotgun by his side, he would sit transfixed, staring out towards the wide, empty horizon.

‘It has been my pleasure to read all your books,’ Himmler continued. ‘Your name does not go unspoken here in Germany – you have a reputation as a great hunter, fearless explorer and respected scientist. You are, after all, the reason the panda, that rarest of beasts, is on show at that museum in Philadelphia.’ He lowered his voice and spoke softly, like a priest. ‘But I am so disappointed it does not reside in our own fine Natural History Museum, right here in Berlin.’

Ernst pressed his hand to his belly to try to silence its rumbling protests; in all the rush this morning, he’d left without eating breakfast, quickly grabbing an apple from the fruit vendor’s cart in front of the station. He was determined to make a serious impression on Himmler. Since being called back to Germany, he wanted to shed the reputation of the famous boy-explorer in order to focus on his studies and finish his doctorate.

‘I am not planning to send you on another hunting mission, though. Well, not exactly. Perhaps a different kind of hunt, yes,’ he said, smiling at Ernst. ‘I have selected you to be the Untersturmführer of a prestigious group in search of the glorious ancestry of the Herrenvolk, our magnificent Aryan race. You may be wondering what it is I am collecting, Schäfer. In truth, it is our dear Führer’s collection really, on behalf of us all.’ He banged his fist on the desk and sent the pens flying over the edge. ‘Lebensraum!’ he shouted. ‘The imperative to reclaim the territory that has been ours from time immemorial.’

Himmler’s pallid face turned beet red as he rose from the chair and strolled around to the other side of the desk, where he stood behind Ernst. ‘You are to bring back evidence of what we already know is the truth – that our pure German blood comes from an ancient warrior race born in the foothills of the Tibetan Himalayas.’

Ernst had heard of this theory, that the Aryan race emerged triumphant from a great cosmic battle between fire and ice. He understood the importance of having an anthropologist on an expedition of that nature, and he knew Bruno Beger would jump at the chance of joining the team. But he didn’t know what Himmler could want from a simple zoologist. How did his own scientific obsession with rare Tibetan birds have anything to do with the tenuous tracing of ancestral links to a mythical super-race? Surely Himmler had checked his credentials thoroughly before calling him back from Philadelphia?

‘Welteislehre!’ Himmler trumpeted, launching into a forceful monologue that commanded Ernst’s drifting attention. ‘World Ice Theory is finally receiving the recognition it deserves, overthrowing that madman Einstein and his Jewish pseudoscience. The Führer has at last accepted it as the scientific platform of the Reich. And rightly so. We know the truth now, that ice crystals are the true building blocks of the universe, not those imaginary atoms. You, young man, will travel to Tibet to head into the bowels of the earth where Fire and Ice went to war, and the ancestors of the German Volk emerged triumphant as Sonnenmenschen. Perfect beings, as radiant as the sun.’

Ernst sat there in silence, listening to the man’s diatribe. These theories espoused by those who worked at the Ahnenerbe, the new ancestral heritage department of the Reich, were certainly becoming popular. Sponsored by Himmler, the gigantic organisation had already attracted some of the top scholars in Germany. Many in its ranks staunchly believed an icy moon once crashed into the earth, destroying an ancient Nordic tribe whose descendants were thought to have survived in the Himalayas.

Ernst glanced discreetly at his watch; it was already 10.15 am. The meeting was taking far longer than he had anticipated. Herta would be getting worried.

Himmler suddenly placed his hand on Ernst’s shoulder. ‘Tell me about this lovely Mädchen you have been seeing lately.’

‘Pardon, Herr Kommandant?’

‘Your little girlfriend, Herta Völz.’

Ernst could almost feel the Reichsführer’s eyes bore into the back of his head. Could the man read minds?

‘You know about her?’ He wiped his brow, not daring to turn around.

‘My records show you joined the SS in the summer of thirty-three, when you were back in Germany between expeditions. A wise move, my boy.’ He patted Ernst on the back. ‘As an SS officer, I think of you as my son. And I make it my business to keep informed about my own family. So, do tell me about your young friend.’

Ernst uncrossed his legs. ‘She is very beautiful.’ He felt himself blushing.

‘It’s okay. No need to be shy with me. It is of the utmost importance we ensure you are with a girl from a healthy German family, who deserves the great honour of marrying one of our purest and finest.’ He returned to his chair.

In spite of himself, Ernst felt like an excited teenager, his words rushing out. ‘Her father presided over the prestigious Heidelberg Völz Pädagogium before moving to Waltershausen. He teaches music now, a passion he passed on to Herta. We grew up together, spending time foraging in the woods. She was always a strong, intelligent girl, and I had a soft spot for her even back then. With all my travels, we hadn’t seen each other for several years, but soon after I returned from America, a mutual friend and colleague of mine happened to introduce us.’ Ernst told Himmler how Herta had moved to Berlin to study flute at the Conservatory. ‘She makes me very happy, Herr Kommandant.’

‘And before you marry she will be attending our fine Reich Bride School, no doubt?’

There was another awkward pause. Ernst had never heard of such a thing.

‘Natürlich. Of course, Herr Kommandant.’

‘Good. Good. We will have plenty of time to learn more about our Herta later.’

Ernst thought he saw the faintest smile creep onto Himmler’s face, but it vanished in an instant.

‘First, we must discuss more urgent matters.’ He slowly opened a file. ‘Our great Deutsche Tibet Expedition. Given your experience in Tibet, together with your hunting skills, you are perfectly placed to lead the team. It is you whom the Reich has entrusted with tracing our ancestral heritage.’

Ernst looked once again at the man across the desk. An anxiously tidy person, his thinning hair combed back, Himmler was hardly the picture of Nordic prowess.

As if he’d read Ernst’s mind again, Himmler continued, ‘Some of us feel that heritage more acutely than others. I only share this secret with those I trust, but I myself am the reincarnation of Heinrich the Fowler, our country’s first king. He was a legendary woodsman, of course, so I am particularly impressed with your own aptitude.’

As Ernst waited for the man to elaborate, he felt pinned to the spot. Though his first impulse was to laugh at the absurd remark, he recognised in the depths of Himmler’s eyes the stealth, patience and determination of a hunter waiting to pounce. This is how prey must feel, Ernst thought, lined up through the sight of a gun, unknowingly waiting for the swift moment of their death.

‘Yes, I would like to send you to Tibet once more. This time, though, you will travel all the way to Lhasa.’

Ernst cleared his throat, realising this was not an invitation. It was an order. Not that it wasn’t his dream to go back to Tibet, especially if he might trek to the foothills of the Himalayas this time. He thought about how Brooky would have laughed his head off at Himmler’s esoteric plan, refusing point blank to have anything to do with it, but things were different in America.

‘I will personally make sure that only the finest of our scientists will be joining you.’ Himmler’s voice was calm and reassuring now. ‘They will be from every branch of science possible, each one a dedicated SS man, like your good self. I want the famed archaeologist Edmund Kiss to be part of the team. I have just finished reading his excellent book about the true origins of Atlantis.’ His voice dropped to a whisper again. ‘Tell me, my son, about your previous trips into Tibet. I am curious to know what the people there are like.’

Ernst cracked his knuckles. Himmler had not yet mentioned anything at all about Ernst’s scientific qualifications; even so, he could feel himself warming to the idea of another expedition. ‘I found them very accommodating, Herr Kommandant.’

‘Yes,’ he said with a smirk. ‘I’ve heard some stories about how friendly their women are.’

‘Oh! My apologies. I wasn’t actually referring to the women, although they do have a certain exotic beauty about them. I meant that, on the whole, Tibetans are hospitable and kind. But they are superstitious and strongly believe in magic, which, of course, as a man of science I find quite ludicrous.’ His words flew out of his mouth like a flock of startled birds.

Himmler seemed not to have noticed the unintended slight. ‘Did you come across any natives with blond hair?’

‘No, Herr Kommandant. The peoples of Tibet are of a much darker complexion.’

The Reichsführer got up from his chair and paced up and down the room, rubbing the back of his neck. He moved over to the window and looked up at the sky. ‘You have a lot to learn, young man.’ He turned to face Ernst, who had beads of sweat forming on his upper lip.

‘But I will take it upon myself to help you understand. Meanwhile, you will meet a group of us for lunch each month to discuss preparations for the expedition. I want you to leave as soon as practicable, which means we have much organising ahead of us. You shall receive further instructions shortly. That is all.’

The meeting ended abruptly, with Himmler raising his right hand in salute: ‘Heil Hitler!’

Ernst rose quickly from his chair. ‘Heil Hitler!’

The sentries guarding the door led him back along the corridor, which was lined with the marble busts of generations of prominent German men. He glanced up at the vaulted ceiling, sunlight pouring in through huge arched windows. Ernst was escorted down a gilt staircase towards the front of the former art school turned Gestapo headquarters. The sentries saluted and waited for him to leave.

Ernst walked back out onto the street and faltered for a moment, deciding which direction to take. Then he strode off, swinging his arms like a toy soldier.

The Hollow Bones Leah Kaminsky

The Hollow Bones implores us to pay careful attention to the crucial lessons we might learn from our not-too-distant history.

Buy now