- Published: 17 May 2022

- ISBN: 9781529176742

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 528

- RRP: $24.99

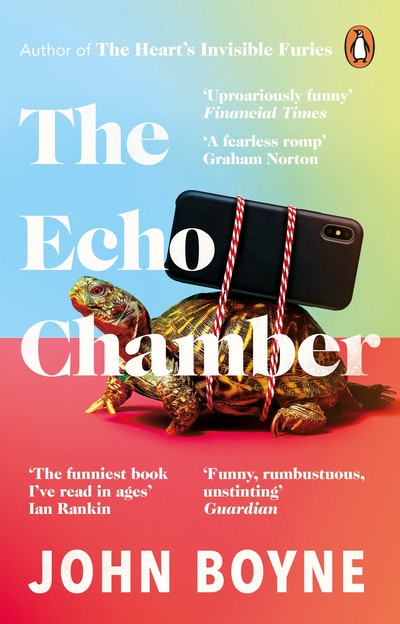

The Echo Chamber

Extract

‘Is Mummy going to die?’ asks Elizabeth, who heard the anguished screams of her mother as the ambulance arrived and watched as the blood soaked into Beverley’s nightdress.

‘Of course not,’ replies her father, although he’s not certain. The first two children’s births took place without any fuss, but this pregnancy has proved very difficult. He’s done everything he can to help Beverley, and the problems she’s encountered have brought them as close as they’ve been in years; the idea of losing her is almost too much for him to bear. And yet, it is to this dark place that his mind strays. The notion of being left to look after Nelson and Elizabeth on his own is overwhelming. He would need to be strong, he knows that, but what kind of life could he possibly hope to give them without the support of the woman he loves? He’s never been a religious man, but he finds himself praying.

A young nurse wanders past, glancing in his direction. He knows what she’s doing. She’s passing by simply to get a look at him, to tell people that she saw that George Cleverley off the telly and he’s shorter in real life, or taller, or fatter, or thinner. Generally, he takes pleasure in his celebrity, but at moments like this, it’s too much. Even the ambulance drivers seemed impressed, and he was certain that one came close to asking for an autograph.

‘Whatever happens,’ he tells his children now, keeping his voice calm and strong in order to reassure them, ‘we are a family. We love each other, we will always love each other, and nothing, absolutely nothing, can ever come between us. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, Daddy,’ they both say, and he pulls them in closer.

A door opens and a doctor steps out, pulling a mask from around her face. George stares at her, knowing that her expression will immediately tell him everything he needs to know.

The doctor is smiling.

‘She’s fine. She’s lost a lot of blood but she’s having a transfusion now and I don’t envisage any difficulties.’

‘And the baby?’

‘A little boy. Premature but healthy. We’ll have to keep him here for a few weeks, but I think he’s going to be okay.’

George starts to cry, and Nelson and Elizabeth stare at him in bewilderment. He holds them tightly. He loves his family. He’s in love with them all.

And at that precise moment, in a dorm room at Harvard University, a nineteen-year-old boy presses the return button on his computer keyboard and watches as the first post on something he’s called ‘The Facebook’ appears:

Mark Zuckerberg changed his profile picture

just now

Monday

THE MILLINER AND THE NOSE

George Cleverley had always prided himself on being a thoroughly modern man, a free thinker who held no truck with the historical bigotries of the previous generation, the societal prejudices of his own or the belligerent intolerances of the next.

After the birth of each of his children, at a time when childcare was still considered the primary domain of the mother, he had done his fair share of nappy-changing, often sitting up with his wife while she administered sleepy midnight feeds and reading aloud to her as she nursed their latest progeny at her breast. He went on marches, protesting against anything that seemed even vaguely objectionable, and wrote newspaper columns criticizing American presidents, African dictators and Russian despots alike. He named his eldest son Nelson, after Nelson Mandela, adding Fidel as the boy’s middle name. On his weekly chat show, one of the most popular programmes on British television, he made a point of ensuring that an even gender ratio was maintained among his guests and, when actresses featured in the line-up, never referred to their bodies or sex lives during the conversation, preferring to focus on their craft and philanthropic pursuits. He considered himself fiscally conservative but socially liberal, was a prominent opponent of blood sports, and had twice been a weekend guest of Charles and Camilla’s at Highgrove. Politically, he was held in high esteem by both the Left and the Right, who considered him a fair and balanced journalist. Although he never publicly discussed his political leanings, he always voted for the person, not the party, and so, over the years, had cast ballots for Tory, Labour and Liberal Democrat candidates alike. In the 2019 general election, exhausted by Brexit, he had even voted for a Green. He sponsored eighteen goats in Somalia and had attended seven Pride marches in the capital, waving the rainbow flag vigorously.

And yet, despite all his hard-earned Woke credentials, his first thought when Angela Gosebourne informed him that he was going to be a father again was: You planned this, didn’t you? To trap me.

At the time, George and Angela had not been conducting their affair for long, no more than five months, and he hadn’t really considered it a proper affair at all, more of a dalliance. He’d never been unfaithful to Beverley before and hated seeing himself turn into that sort of man, but his marriage had become strained in recent years, much of their communication taking place over WhatsApp rather than face to face, and Angela’s attraction to him had taken hold of his ego and given it a good shake.

Although he was fond of her, he had never imagined their relationship would have any long-term consequences. She had a tendency to pepper her speech with foreign phrases co-opted into the language, a too desperate sign of her erudition, and had a laugh that grated, forcing him to keep witty remarks to a minimum. Ultimately, he’d decided to end the liaison but, a few days after the break-up, she’d phoned, asking for one final roll in the hay and, being weak, he’d succumbed to her erotic invitation, which, in time, had led to today’s meeting in a Kensington wine bar, where she’d delivered the news by placing her hand over her glass when the waitress tried to pour, saying, ‘I can’t. Je suis enceinte.’

‘I don’t want anything from you,’ Angela insisted now, taking a compact from her handbag and dabbing at her face with a powder puff, another habit that aggravated him. ‘You can be a part of this baby’s life or not, exactly as you wish. If you’d prefer to have nothing to do with him, then naturally, I’ll understand. But there’s no changing things. It’s a fait accompli.’

‘Him?’ asked George, a small twinge of paternal pride asserting itself over the dismay. ‘It’s a boy, then? You’re sure?’

‘Well, not sure, no,’ she admitted. ‘But a mother can sense these things.’

‘Nonsense,’ he replied.

‘You’ve never been a mother, George, so you can’t know.’

‘Perhaps not, but I don’t hold with old wives’ tales.’

‘I’m not an old wife,’ countered Angela. ‘You’re confusing me with Beverley.’

‘I mean, it’s all very well to say that I can be as involved as I like,’ he continued, ignoring the barb, ‘but it’s not quite as simple as that, is it? If I throw myself into fatherhood again, which I’m loath to do at my age, then I’ll almost certainly lose Beverley, and the children will take her side, as they always do, so I’ll lose them too. But if I don’t, if I just walk away, then I’m a scoundrel and, twenty years from now, when I’m in my dotage, he, she or they will show up at my front door complaining of abandonment and blaming me for everything that’s gone wrong in their life. I’ll be eighty years old by then and, frankly, I won’t need the grief.’

‘They?’ asked Angela, frowning. ‘Is there a history of twins in your family?’

‘No. Why do you ask?’

‘You said they ?’

‘I understand that some people prefer the third person plural for a pronoun,’ he replied, having recently interviewed a pop singer on his show who’d insisted upon this, leading one of the cameramen to be fired for calling them Sibyl, after the Sally Field movie about the woman with multiple personalities.

‘Well, as he’s still the size of a peanut,’ said Angela, ‘he hasn’t yet made any such preferences known. So, let’s not overcomplicate matters.’

‘But you take my point,’ said George, summoning a waiter over and ordering an Old Fashioned on the rocks with two twists of citrus rind rather than the traditional one. ‘Now that you’ve told me, I’m obliged to react in some way, even if that reaction is to do nothing at all. If I choose not to be involved, then I’m still involved by the nature of not being involved. Do you follow?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘And then there’s the financial aspect.’

‘Now that’s beneath you,’ she said. ‘If you think I’m after your money—’

‘I don’t think that at all,’ he replied. ‘But you’d be entitled to some. And so would the child. Obviously, I wouldn’t shirk from paying my fair share. I wouldn’t want him to suffer any deprivations as a consequence of his bastardry.’

‘You know, for such a dyed-in-the-wool liberal, you use some very archaic terms. It’s rather de trop, if you don’t mind my saying.’

‘These are legal terms, nothing more.’

‘I’m not sure that’s true,’ said Angela.

‘And I couldn’t keep something like that from Beverley. She goes through our bank statements every month with all the urgency of a sniffer dog at international arrivals, just after the planes from Thailand have got in.’

‘George!’ she said, laughing a little. That grating laugh.

‘Well, it’s true. A few weeks ago, we got into a ferocious argument about why I’d spent thirty pounds in Simpson’s of Piccadilly when we have an account at Hatchards.’

‘Well, I’m not surprised,’ replied Angela, taking a sip of her water.

‘Since Simpson’s closed its door in the mid-nineties.’

‘You know what I mean,’ he said with a sigh. ‘Waterstone’s, then. With an apostrophe, I might add. It offends me that a book chain, of all places, cannot punctuate correctly.’

‘Speaking of which,’ said Angela, nodding at the canvas bag resting on the table between them, a large W emblazoned across the front.

‘You’ve been back, I see. What did you buy?’

‘A new biography that interested me,’ he said, passing the book across.

‘Eight hundred pages long. When was the last time you read an eight-hundred-page book? I never seem to read any more,’ he added. ‘I’m always on my laptop or my phone. Anyway, my point is that if I suddenly start transferring huge wodges of cash from my bank account to yours every month, Beverley’s going to ask why. And if she finds out that I’ve fathered a love child, she will almost certainly divorce me.’

‘And would that be the worst thing in the world?’ asked Angela.

‘It would, yes. I love my wife.’

‘Then why did you cheat on her?’

‘I don’t like that word,’ he said, grimacing a little. ‘Cheating is for cardsharps, carnival barkers and presidential candidates, and I am none of those things.’

The Old Fashioned arrived but with only one citrus rind, the waiter explaining that the bartender had declined to make it with two.

‘What do you mean, he declined?’ asked George, looking up at him irritably. ‘What gives him the right?’

‘François posts images of all his cocktails on Instagram,’ replied the young man. ‘So he can’t take the risk. Last month, he substituted Aperol for Campari in a Negroni and he received death threats from purists.’

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ said George, waving him away, too weary to argue.

‘Of course, if she threw you out,’ continued Angela, ‘it’s not as if you’d be homeless.’ She looked down at the tablecloth and tapped her fingers against it. ‘I mean, you could always come and live with me, if you wanted. Live with us, that is. The baby and me.’

He narrowed his eyes, hoping that she was joking.

‘But you live in Croydon,’ he said.

‘What on earth has that got to do with anything?’

‘If you don’t know, then there’s very little point in me trying to explain.’

‘I’ll have you know that Croydon is becoming quite gentrified these days.’

‘I just prefer a postcode that begins with a SW, that’s all,’ said George.

‘My father instilled certain values in me from the start that have stood me in good stead over the years. Carrying a monogrammed handkerchief, for example. Having a good tailor. Matching one’s belt with one’s shoes. The stuff of civilized living.’

‘You can’t make life decisions based on letters of the alphabet.’

‘I don’t see why not.’ He took a sip from his drink, then a larger draught, then finished it entirely. ‘I suppose you want this baby, do you?’ he asked, keeping his tone casual and his implication vague.

‘I’m thirty-eight years old,’ she replied. ‘So yes, I do. I might not get another chance.’

‘You do know the world is overpopulated as it is?’

‘Then one more won’t make much of a difference, will it?’

‘Of course, the Chinese had the right idea with the one-child policy.’

Before they could debate this, the Shadow Home Secretary, who had been seated on the other side of the room, stopped by to say hello and George stood up, kissing her on both cheeks and congratulating her on her recent promotion.

‘I must say, you look marvellous,’ he added. ‘Power agrees with you. Or shadow power, anyway. And, correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re wearing Caron Poivre, aren’t you?’

‘How did you know?’ she replied, beaming.

‘I have a good nose,’ he said, smiling as he tapped the proboscis in question. ‘Arturetto Landi once gave me a tour of his studio and said that I could have had a career in it.’

‘Being a nose?’

‘Being a nose.’

‘It’s good to have options. Hello,’ she said, turning to Angela.

‘Hello,’ replied Angela, standing up and shaking her hand.

‘This is a friend of mine,’ said George, looking a little rattled. He would have preferred if Angela had pretended to be a deaf-mute and kept to her seat. ‘Angela Gosebourne. Angela is a milliner.’

‘A milliner?’

‘Yes, a milliner.’

The Shadow Home Secretary considered this for a moment, as if she was not entirely sure that she understood the word. ‘Do you mean hats?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ replied George. ‘Hats. And, you know, fascinators. And what have you . . .’ he added, trailing off.

‘How interesting. I don’t wear hats very often. I don’t think I have a head for them.’

‘Everyone does,’ said Angela. ‘You just have to find the right hat for you, that’s all.’

‘No, you’re quite wrong,’ replied the Shadow Home Secretary, who had been concerned about the size of her head since childhood, when the children in her school suggested that she had been immortalized on Easter Island. ‘But I wish you well in your endeavours all the same.’

‘Thank you,’ replied Angela, sitting down again.

Some more conversation was exchanged between the principals before George resumed his seat too.

‘That was very odd,’ said Angela. ‘Why did you tell her that?’

‘Tell her what?’

‘That I’m a milliner.’

‘I momentarily forgot that you’re a therapist, that’s all.’

‘What nonsense.’

‘All right, I didn’t want to say anything incriminating. She knows Beverley. It wouldn’t do if news of this lunch got back to her.’

‘And why is being a milliner any less incriminating than being a psychotherapist?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said, throwing his hands in the air. ‘I panicked, that’s all. Sometimes, I find myself at a loss to explain my actions.’

‘The milliner and the nose,’ said Angela, considering the careers they might have had in the alternate universe he had created. ‘It sounds rather like a children’s fairy tale, don’t you think?’

‘Children’s fairy tales are notoriously dark,’ he replied, ordering another drink and wondering whether it would betray his emotions too much if he ordered a double. ‘Full of gruesome murders and anthropomorphism.’

‘And cannibalism,’ she added. ‘Think of Hansel and Gretel locked away in a cage above the witch’s fire. Being fattened up for the slaughter.’

‘I’ll avoid that one when I’m reading our son to sleep.’

‘So that’s something that you can see happening?’ she asked, looking up hopefully.

‘Well, possibly. We’ll see.’

‘But you’ll give me an answer at some point, though? About whether you want to be involved?’

‘Of course,’ he replied. ‘I’m not saying yes, but I’m not saying no either. I’m sorry I can’t be clearer, but I need some time to think. Is that all right?’

Angela sighed and stood up, putting on her coat. ‘I suppose it will have to be,’ she said. ‘Sometimes I wonder what it is that I ever saw in you, George, I really do.’

She leaned over to kiss him on the top of his head. His thick white hair was one of his most attractive traits, reminding her of a bichon frise puppy. ‘Enjoy your book,’ she said. ‘All eight hundred pages of it. I’ll wait with bated breath for your call.’

The Echo Chamber John Boyne

From the author of The Heart's Invisible Furies and in the wake of a hugely successful hardback publication, The Echo Chamber is 'uproariously funny. The world has never needed satire more urgently and Boyne delivers in spades.' (The Sunday Times)

Buy now