- Published: 17 August 2021

- ISBN: 9781761041938

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $24.99

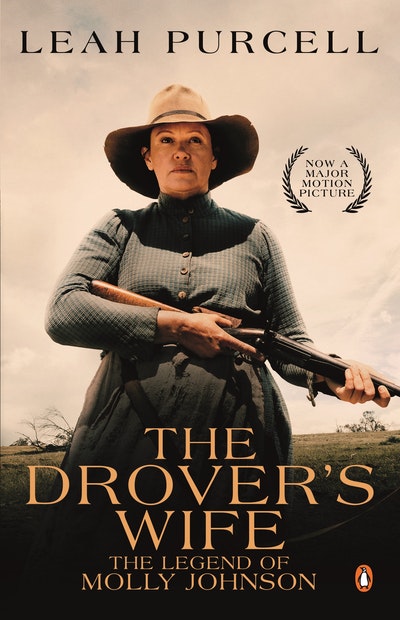

The Drover's Wife

Extract

Prelude

1913

I love the snow gum.

Its stout trunk strong . . . beautiful coloured patterns appear when wet; a gift from God.

The sturdy tree’s limbs outstretched, waiting to take the weight of winter . . . the weight of you.

Oh, to see these trees after an autumn shower . . . it’s this rare beauty that reminds me why I stay . . .

Late one evening Daniel Johnson sits alone on the verandah of a newly renovated homestead, reading from a tatty notebook, his lantern light low. The notebook is sixteen years old now – a collection of sketches, poems and memories. He knew he had to put it all down somehow. From the moment that spurred the four of them – Danny, Joe Junior, Henry James and little Delphi – to run into the mountains to be with them, and everything he learnt in those four short years. Their knowledge ancient beyond comprehension, and there was only so much they could share. Time and society were against them.

Now a man of thirty-two years, Danny flicks through the notebook, and the images he’s sketched look as though they are animated. He stops on a page that features a full moon, the many rings he’s drawn representing the moon’s larger-than-normal halo of light; a powerful glow and energy, bringing unrest to the land.

Danny’s thoughts race back to the moment that was the inspiration for his poem. It was suggested by her, Louisa. ‘Write a poem, perhaps? A way to ease the pain . . . the hurt and the loss. You don’t have to show it to anyone or share it. It’s just for you, Danny.’

He was taught to write poetry by Mrs Louisa Clintoff, a newspaper proprietor, a friend, a long time ago now. This poem grew from a time he remembers well, too well. The harrowing moments he has kept to himself, never shared before, not even with his siblings. It is his job to protect them, even now they’re all grown.

Contained between the pages of the old notebook is the story of a great woman, strong, steadfast, reliable and loving: his ma, Molly Johnson, nee Stewart. Daughter of Jock Stewart, Scotsman and jackof-all-trades. It’s the story of a mother’s love, fierce and true. And of a black man who was noble, wise and gentle, a warrior of ancient proportions – but unfortunately not Danny’s father. Memories of cautious meetings, bonding and the sharing of stories. Lessons were learnt and a mutual understanding and genuine respect developed from the man to the boy and from the boy to the man – Yadaka and Daniel Johnson. There were exchanges around the fire pit, but Yadaka’s stay was short. The full moon was to guide him away, north, back home to his mother’s country.

But that first winter’s full-moon night became momentous in more ways than one . . .

One

1893, Late May, a few hours before midnight

I’m dead! thinks the badly beaten Molly Johnson, who lies foxing on the ground. Her bloodshot eyes dart back and forth as she gathers her thoughts. What should I do next? Her heavy breathing makes the loose sod under her bleeding nose and swollen lips spray.

She’d heard that when death is inevitable, life flashes before your eyes. Well, to hell with that, thinks Molly. I have my children to live for.

She knows she must bide her time. Firstly, for herself. To regain some strength and think on her next course of action, because she is no match for these two bastard stockmen. A strong cuss word crosses her mind that she would love to call them, scream to the world. But only the majestic mountain range in front of her two-room shanty will hear, and echo the word back, slapping her fair in her battered face. And there is no one here who cares for her opinion. She’s just a woman.

A moon large and full with many glowing rings sits high in the night sky, silver beams spilling down to spotlight the front yard of Molly’s home. Large boulders sit behind the hut and sparsely placed white sallees border the perimeter, their trunks shimmering in the moonlight, the shanty hidden in the bush to protect or hinder?

Molly cautiously lifts her head just enough to see the two stockmen as they catch their breath. The one who looks like a boy in physique wears an oilskin coat and a woman’s petticoat skirt over his britches. He takes a rope from his belt. Pulled down low, his hat casts a shadow over his face. He ties up the legs of an unconscious man who lies behind the tree-trunk log that sits next to the fire pit. Ever so slightly, Molly tilts her head to see the other stockman who did all the hitting. He’s helping himself to her water barrel, the barrel that she and the children fill, walking the dangerously steep decline to the banks of the Murrumbidgee, and back again. He’s built like a bullock, and every bone in her body aches with pain, especially her head. But pain is not new to her. She has felt wrath before and is hardened to it. And that just may be her undoing tonight.

The older stockman with the full red beard coughs, water spluttering from his mouth. The droplets on his beard sparkle like diamonds in the moonlight.

Choke on it, ya bastard, she thinks. The distaste for him makes Molly want to spit – or is it the blood pooling in her mouth?

Fuck, she thinks, as she lowers her head. She really could be done for here. Then, there before her, she sees her axe, large, menacing and sharp. It lies in the dirt beside the old chopping block, stained on one side with something that looks like blood.

The younger stockman asks, ‘How many will he make?’, pointing to the unseen man.

‘Thirty-eight.’

‘Is that all? Slowin’ up in ya old age.’

‘I’m not gettin’ paid.’

The older stockman pours the rest of the water over his face, and it cascades down his beard. He takes the rope from his belt and begins to knot a noose.

The night sits in silence, anticipating what’s to come.

From behind them comes a gut-wrenching, ‘Aaaaarrrhhh!’ Molly has picked up the axe and with all her might tries to swing it with force. The stockmen spin on their heels to see her standing before them with the axe raised. She looks like a crazed woman, her hair wild and woolly like the thicket found in the high country, menacing and fierce, her stance wide. She swings the axe and the men scatter. The younger one runs, dropping the secured legs of the unconscious man heavily back onto the log.

Molly grabs at her ribs as the axe hits the ground. Sharp pain rips through her upper body – her ribs are broken. Her breath catches as she gasps with pain. She’s angry that her attempt to connect with either of them has failed. What the hell was I thinkin’? She should have lain on the ground, pretended to have been knocked out and hoped they left with just him, and took their revenge out on him. Not that she would wish that upon him, but if it was to save her life and save her being taken from her children, then so be it. Sometimes that’s just how things are done here, in the middle of nowhere, in the alpine country of the Snowy Mountains. Every child needs their mother.

Molly, feeling a fool, senses every aching part of her body: her swelling face, the red welt marks on her cheekbones, her throbbing jawline and her tender ribs. She tastes the salt of sweat and blood dribbling into her mouth as she sucks in air, exhausted, and leaning on the axe for support now. Using all her strength, she tries to lift it again. Her effort is feeble and the two stockmen laugh at her. The one with the boyish physique bares his rotten teeth, sneering. Molly struggles to hold the axe up. Her breath runs shallow and rapid.

The red-bearded stockman shifts his shotgun. ‘Put it down, or I’ll put a bullet through ya.’

Molly doesn’t move.

‘You’re a fuckin’ disgrace, woman.’ He indicates to the pants and boots of the tied-up unconscious man; the log by the fire pit obscures his upper body. ‘Puttin’ ya life on the line for this low-life.’ He spits the words at her in disgust.

Molly’s battered face is streaked with tears, running with her sweat, snot and blood. The younger stockman asks the other, ‘Ya gonna shoot ’er?’

The older stockman takes his shooting stance. Molly knows she can’t win. She steps forward. He’s quick to cock his shotgun; the other raises his pistol. With an anguished, guttural yell, she brings the axe down hard into the chopping block; iron to hard wood, sparks fly. She steps back, knowing her demise is near.

The red beard lunges towards her. Molly cowers. ‘My children, please! My children!’

She backs away and he grabs her by the arm, his dirty, hairy fist raised, punch after punch, her head snapping back. He stops, releasing his hold. She drops. The younger stockman marches towards Molly sprawled out on the ground . . .

The Drover's Wife Leah Purcell

IN CINEMAS NOW, from Leah Purcell, named as one of the 100 figures shaping Australia’s creative future.The Drover's Wife is utterly authentic, brilliantly plotted, thoroughly harrowing and entirely of our times exploring race, gender, violence and inheritance.

Buy now