- Published: 14 September 2021

- ISBN: 9781761045998

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $24.99

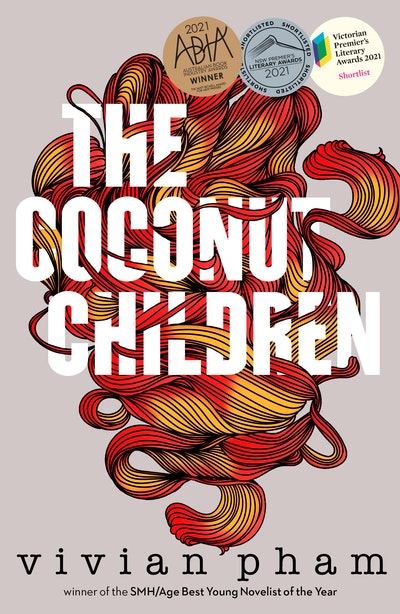

The Coconut Children

Extract

Silence is another kind of drowning. There were the pirates, too, with cunning smiles that stretch whole horizons and machetes spoiled by saltwater rust, who stole generations of gold and all the pretty girls. Look at your son, the inheritor of your sun-soaked skin. The rest of the world may forget your death but he is the only evidence you ever lived.

Ancestors, I have heard stories about you. You and I are two kinds of spirits. My father has not even imagined my coming. I am two decades away. I am mist unborn, a gathering of dew drops, a thousand tricks of light not yet pricked with blood. Yours is an earthbound body that disobeys gravestones. Your disarrayed bones each have a mind of their own. You miss your missing limbs. Your hand writes love letters to you. Your spirit is steeped in enough suffering to last eternity. You are acquainted enough with death to keep it running other errands.

Won’t you give him a blessing? Just enough to blow the boat on its way a little quicker. Perhaps some spare, to keep in his pocket for the next journey.

My father thinks about the bombs and baby blossoms dropping all around the world. That old poem comes to mind. The one written by a miserable leper who wanted someone to love but could never bear being seen.

Who wants to buy the moon? I’ll sell it to you.

O, to be young and dirt poor, thinking that the world belongs to you. Turns out to be almost true.

Chapter 1

Morning Glory

On the day of Vince’s release, you could hear his laughter thundering through the entire neighbourhood. It was February 1998. The centre of summer. The timbre of his voice shook the trees and rumbled through the streets, tearing through the delicate seams of silence. He was with his posse of old friends, the type of kids that carry knives in their back pockets. Maybe it was a trick of the light but it was almost as if he had never left – there was Vince, sipping on his sugarcane juice. There was Vince, with his gleaming gold necklace, the jade Buddha nestled contentedly between his newly defined pectorals. There was Vince, with his sunny smile and over-gelled hair, lying in the Woolworths trolley as somebody less important pushed him along. There was Vince, never less than vibrant, always pulsating, always looking as though he was about to break out of his own body.

He leant his head against the back of the trolley and looked up. As though the sky were an upside-down valley of fine powders, he sucked in a violent breath and closed his eyes to ecstasy.

‘The air smell different?’ his friends asked, amused. They watched how his face, once young and boyish, caught hold of the light, how it transformed again and again with every ripple of sunshine, as if to resist its own identity. What kind of secrets did the past two years hold?

Vince’s body rocked to and fro against the rattling trolley cart which rushed into gusts of air. He smelled the cooking that seeped from the houses and the stench of soiled mattresses on the curb.

‘Nah,’ he said finally. ‘Smells like home.’

Everybody was his friend. The stray cats with swollen eyes purred as he tossed them fried chicken. The Bible-swinging madman on the street corner, Vince smiled at him too. There was no pity in his eyes as he watched the man preach the Book of Revelation to a gathering of pigeons; he was so unlike the other passers-by who scowled and lowered their gaze. Even the sun reached down from its interstellar home to touch Vince’s skin and beam into his eyes, saying, Look at me, look at me.

Cabramatta welcomed her son back with quiet rejoice. The sidewalk trees, which usually surrendered under the battlements of dusty brown apartment buildings, seemed to straighten their spines. Further up the street, front yards spilled with offerings to him. Those who lived in their own houses took advantage of every inch of property that bore their name. In their gardens, they planted massive lime, dragon fruit and mango trees. Families boasted bathtubs of fish mint, coriander and sawtooth herbs and draped luscious winter melons on hardwood arbours. While their neighbours were cultivating personal rainforests, the apartment dwellers chafed within the confines of old bricks and concrete slabs. Some were fortunate enough to enjoy garden views from their balconies, but those who lived in units which faced inwards could only stare miserably into each other’s eyes as they hung their laundry out to dry.

The trolley-cart came to a halt and Vince jumped out. He crept into a garden and stared in awe under the dappled shade of a mango tree. He intended to only take the lone fruit that had fallen on the grass, but the others hung lowly on the branches blushed before him, draping the sunshine over their voluptuous figures, beckoning. He tore the two chubbiest mangoes from the tree, scooped the mushy one up from the ground and hopped back into the trolley. After prying apart the golden skin, he drank from its gently fermenting flesh. Then he whipped out his pocket knife and carved into the others. (He only ever used this blade for stolen homegrown fruits. In times of combat, he was imaginative with his choice of weaponry – he knew, for example, that the handle bar of the trolley cart he was riding in encased a usefully weighty pole.) Vince grinned as he offered slices to his friends, his mouth and fingers dripping with sap and syrup.

Mothers stood vigilantly, perched atop their apartment balconies like hawks. Across the neighbourhood, little boys set down their Pokémon cards and peered through the blinds, silently praying for a miracle: to grow up as big and strong as the neighbourhood menace. The glossy lips of prepubescent girls breathed life back into his name. Vince. The legend was alive and let loose on the street.

‘He’s gotten bigger, taller. I heard all he’s been doing in there is training.’

‘What got him in there in the first place?’

‘Who’s he coming for now?’

‘Look at his arms!’

Sonny watched from her bedroom window. Held her breath and the windowsill for dear life. For her, Vince’s return was something like a crack of light entering a prison cell. Since he had been taken away, it seemed a mist had settled over Cabramatta and their suburb had gone to sleep. The world was only awake when Vince was there to see it.

Now he was back. Wearing the same t-shirt he had left in, his back muscles rippling under the translucence of worn cotton, a few small holes revealing more intimate areas of skin, by courtesy of some peckish moths. And as Sonny watched him laugh with his mouth wide open and his neck craned as if in defiance of the sun, she tried to figure out what exactly this could mean for her. She hoped that maybe he would catch her eye and stop mucking around for one second, hold her gaze and make some kind of telepathic promise. Like: You look beautiful, I’m going to rescue you from your crazy mother. But of course, she wasn’t in his line of sight and he was too concerned with pulverising glass bottles as he raced down the footpath to notice her anguish. Besides, she wasn’t even sure if he remembered who she was. Sonny receded from the window, relieved she couldn’t be seen like this. Framed by glass. Stuck in her bedroom. Soiled by the unspeakable.

The procession passed. He was gone. How careless he was, to leave a girl wanting to slow dance with his shadow and not even stopping to ask for her hand. Sonny had trouble falling asleep that night. She tossed and turned, conjured up all sorts of fantasies. See: Sonny walking along a crowded street, skipping and giggling with the incandescence of a little girl, Vince’s arm easy over her shoulders. When she woke up, she thought to herself, Shit, this isn’t how I was raised – to aspire to be under the arm of a boy, and a street boy at that! The kind that sold stolen car parts as a hobby and had developed a stomach for alcohol ever since he was twelve, the kind of street boy who, if you stripped him of his hair gel and booming voice, probably resembled some kind of mangled cat.

Was Vince the only one that had entered her heart? It was true that in the last couple of years, she had fallen in love with practically every male creature to have ventured within a five-metre radius of her. The KFC employee with bright green braces, who gave her a look of tender understanding when she had confessed to him her deepest desire: six Wicked Wings and a regular coleslaw. The curly-haired boy whom she’d witnessed help an elderly man with his groceries up a broken escalator. This one had a special place in her heart. She carefully memorised his facial features and body measurements, had kept the image of him in her mental depository for over a year now. Revisited him every so often to freshen him up and keep him from fading into a shadow. Whipped him out on a rainy day.

But by far Sonny’s most serious commitment to date was to her Chemistry teacher. Mr Baker had a wispy tuft of hair left on his head, a protruding stomach and an odd nasal voice. In spite of these minor deformities, her nonexistent contact with boys her own age translated into acquiring a taste for older, wiser, physically unattractive men.

She pined for the 75 minutes of class with him three times a week, during which he called out her name for the roll. She would have to mentally prep herself, clear her throat and chant a mantra or two before the crucial moment. She never answered straight away, always waited for him to look up and scan the room before she said ‘Here’ and he found her. Ah yes, that little twinkle in his eyes, that slightly lifted brow, that look of bemusement, curiosity, perhaps even desire. Here was ample material to mull over when she was alone, making Mr Baker a convenient target for the violent ammunition of her love thoughts. In her mind, their affair was so artfully conspired that they had managed to keep it a secret even from reality.

As Sonny prepared breakfast, she listened to the eggs on the skillet, singing to her soul in spits and sputters. How did Vince like his eggs? Breakfast in juvenile detention centres couldn’t have just been out of a can. The hospitality there must be Michelin-starred – after all, as far as she could tell, the two-year stay had worked wonders on Vince. It had nursed his metamorphosis. There, he’d grown out of his larval stage and taken the form of an ultramasculine butterfly, boasting a chiselled jaw, eyebrows blackened and as sharp as swords, and that same winning smile. He had grown much taller too, and he looked hard and firm all over. The topography of his body was so vast, you’d dream of hiking the famous Deltoid Highlands, Trapezius Valley and Abdominal Alps. Even the colour of his skin testified to his good health. The sun might have blasted you with freckles and turned you red, but Vince soaked up all that light and emitted it in shades of caramel candy. Of course, she’d only seen him ride past her house, caught a glimpse of him reclining in his chariot, his hair too stiff to catch the wind. Sonny needed much more time to study his subtleties, his finer details. But the mere thought of him made her head spin, and her heart feel like a simile – a psychedelic experience that she’d felt only once before, when listening to the second verse of her favourite Backstreet Boys song and hearing It seems like we’re meant to be.

Eventually getting a grip on reality, Sonny glanced at the clock and realised it was almost time for school. She rushed to the bedroom she shared with her little brother and grandmother. Bà ngoại was sleeping soundly in her separate bed. When she wasn’t drunk, she looked like an off-duty guardian angel. Oscar lay on the bottom bunk bed. He was so lost in his thoughts he didn’t even notice her come in.

‘Morning,’ Sonny said brightly. ‘Break any bones in your sleep?’

‘Not this time,’ he mumbled, rising slowly and easing his feet onto the ground.

‘That’s got to be a good sign for your first day. Come on, we’re gonna be late.’

Oscar nodded and tugged the corners of his mouth into a quick smile. It took eight steps to reach the kitchen. He sat down and had his eggs, patiently waiting for Sonny to go and have her morning puff – of her asthma inhaler – so he could pour his glass of milk down the sink. He hated the way the heavy liquid slid down his throat, and, even more so, his sister’s empty promises of its supposed magical bone-strengthening properties. He was convinced he’d been conned his whole life by dairy farmers.

To say that he was nervous about his first day of high school would be the world’s biggest understatement. Unlike most loner kids, poor Oscar didn’t even have the luxury of fantasising about who he could become in high school. Could he be the class clown? The sports star? The surly but sensitive poet that girls secretly swooned over? No, the label he’d be stuck with was the same one branded onto his forehead the very day he’d entered this world: the kid with that bone condition.

He had long before prophesied his high school experience, the images flashing through his mind with brutal clarity. See: a whole cohort of rowdy boys playing pranks on teachers, drawing penises on any surface with permanent marker, dangling each other’s backpacks above the train rails, throwing footballs to one another across the corridor. Amidst this ruckus, cut to Oscar, staring into his locker until it no longer seemed sensible, surrounded by people but painfully alone, scraping his crackers in some cheese dip.

The doctors called it ‘low bone density’ but he called it a family curse. It meant his bones were so fragile a careless shove could cause fractures on impact, or that was what his mother said, anyway. Put him in the nearest public school with the roughest teenage boys to ever make it past Year 6 and you’d better have the ambulance on speed dial.

Forget broken homes, these boys were raised in the midst of hurricanes, moulded by chaos, breastfed by wild boars, it seemed. While other boys his age were worried about the pungency of their deodorant and making the cut for the basketball team, Oscar’s mind was chiefly occupied by low-risk strategies of manoeuvring through crowds. With his entrance into high school, he tried to ditch the negative mindset and instead adopt a more practical methodology. The plan was simple: find a group of gentle-looking boys and stick to them like glue. Look for the kids with cowlicks and their lunches packed with neatly cut carrot sticks. Learning disability kids were the only ones with any humanity; this was a maxim that still rang true throughout the years.

After Sonny had finished preparing their sandwiches and Oscar had brushed his teeth, they both changed into their uniforms and began to make their way to school. They left their mother’s sound snores and locked the front door, skipped down the two creaky wooden steps and concrete path. It was warmer outside. A sleeping cat on the other side of the road seemed to be in agreement with the weather. The sun was low and lustrous, casting morning glory on all of Cabramatta.

‘Break a leg!’ Sonny called. She stood at the gate of the Boys’ School and waved.

He glanced back at her over his shoulder. Gave a halfhearted smile. Proceeded along his path. She stood for a short while to watch him walk into the school building. Every time a bigger boy came close to her skeleton of a brother, her stomach lurched.

She started down the opposite side of the street towards the Girls’ School and stopped to admire a bunch of freesias that bloomed from the embankment, on the other side of the fence. Year 11 was a milestone, the crucial time when the girls traded in their slouchy chequered dresses for skirts – skirts! It made a whole world of difference – you could customise the exact amount of leg you wanted to showcase and enjoy a complimentary breeze to air out your clammy thighs. More than anything, it was a clear signal to the rest of her school that Sonny was older, a senior, and therefore of a more respectable status, a critical detail that was often overlooked due to her short stature. With this skirt in hand, she thought, she’d no longer fear being mistaken for a Year 7 and being simply bypassed in the canteen line. With this skirt, she’d no longer have teachers asking her ‘Are you lost?’ in hallways. This was her ticket to maturity; she was convinced the immutable sovereignty of the school skirt would take her from where her half-assed growth spurt had left off.

Past the school gates, Sonny spotted her best friend, Najma, sitting on the silver seat that faced the basketball court. This was their first meeting since the beginning of the school holidays last year. The two embraced in a clumsy hug and settled into their usual routine. They sat side by side, absorbed in in-depth commentaries about the people that walked past them.

On Cheyanne, a volleyball player who never spoke to anyone and put her head down to sleep in every class: ‘She’s so pretty but . . . I mean there’s nothing bad about her, but there’s nothing good either. She doesn’t do anything.’

‘I don’t know, I find her pretty mysterious.’

‘Or just hungover.’

The Coconut Children Vivian Pham

From the winner of the SMH/Age Best Young Novelist of the Year and the Matt Richell Award for New Writer of the Year. Growing up can feel like a death sentence

Buy now