- Published: 15 October 2019

- ISBN: 9780552170925

- Imprint: Corgi

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $24.99

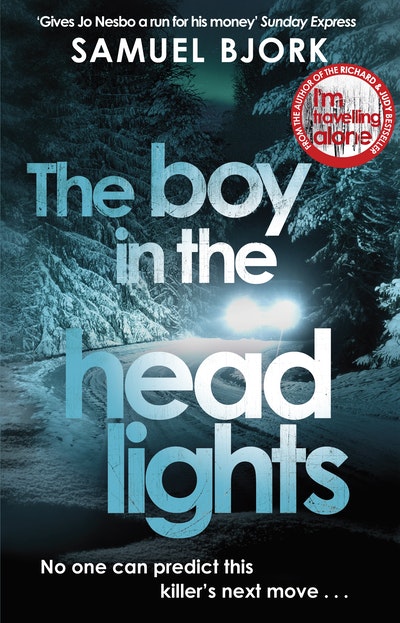

The Boy in the Headlights

From the author of the Richard & Judy bestseller I’m Travelling Alone

Extract

On Christmas Day 1996 a man was driving across the mountains on his way home from Oslo. He was seventy-one years old, a widower, and he had spent Christmas with his daughter. He usually loved this road, for two reasons. Firstly, he didn’t care much for the city, though it always did him good to be with younger people and their constant activity. The second reason was being surrounded by this magnificent landscape. Forests, wide expanses, mountaintops, lakes; every season was equally breathtaking. Norway at her best. True beauty as far as the eye could see. Winter had come early this year and, once the magical snow had settled, it was like driving through a quiet and enchanting postcard. Usually. The old man’s eyesight was poor and he had tried desperately to leave early in order to enjoy the drive home. In the daylight. Only this time he hadn’t left early enough. The darkness. He didn’t like it. Sitting at home in front of the fireplace was fine – then he didn’t mind at all that the world was spinning on its axis and that now it was his turn to be surrounded by night, not at all; at times it could even be cosy. He would pour himself a tipple. Snuggle up on the sofa under a blanket while the nocturnal wildlife woke up outside and the cold took a hold so strong that the thick timber walls creaked. But being out on the roads? This far from home? No, he didn’t like that. The old man slowed down and moved his face even closer to the windscreen. He had bought extra-bright driving lights for the car for emergencies like this one and he switched them on as the clouds in the sky blocked out the last of the faint moonlight. An icy, silencing darkness descended upon the landscape. The old man took a deep breath and briefly considered pulling over and sitting it out. Madness, of course. It was almost minus 20°C outside, and he was miles from any populated areas. There was only one thing for it and that was to keep going. Do the best he could. The old man was about to turn on the radio to find a station that would keep him awake when his headlights caught something which made him slam both feet against the floor.

Good heavens!

There was a creature on the road ahead.

What the . . .?

Fifty metres.

Twenty metres.

Ten metres.

He pressed the brake pedal frantically, feeling his heart leap into his throat, his knuckles whitening on the steering wheel, the world almost imploding in front of his eyes before the car finally stopped.

The man gasped for breath.

What the hell?

A small boy was standing on the road in front of him.

He didn’t move.

His lips were blue.

And he had antlers on his head.

ONE

APRIL 2013

Chapter 1

The boy with the curly hair sat on the back thwart in the small dinghy, trying to be very quiet. He glanced furtively at his father, who had the oars, and felt flushed with happiness. He was seeing his dad again. Finally. It had been a while since the last time, since his mum had found out what had happened during that trip. In his dad’s house deep in the forest – in the mountains, practically – the house his mum called a shack. The boy had tried to explain to her that it was OK that his dad didn’t make the kind of dinners she cooked for him, and that he smoked inside and kept a gun in the living room, because it was for shooting grouse, not people, but his mum had refused to listen to him. No more visits; she had even called the police, or maybe not the police, but someone who had come to their home and spoken to him at the kitchen table and written things down in a notebook, and after that he hadn’t been allowed to see his dad. Until now.

The boy wanted to tell his dad that he had read books since his last visit. About fishing. At the library. That he had learned the names of many fish – whitefish, char, blenny, trout, salmon – and that he now knew there wouldn’t be pike in a lake like this because pike liked hiding in the reeds. There were no reeds here, just bog straight to the water’s edge, but he said nothing because he had learned not to. When you went fishing, you weren’t supposed to talk; only in a very soft voice and only if his father spoke first.

‘First trip to Svarttjønn this year,’ his father whispered, and smiled to him through his beard.

‘And it’s special every time,’ the boy whispered back, and felt once more the wonderful rush of love that flooded over him whenever his father looked at him.

The boy had tried explaining this to his mum over and over. About his dad. How much he liked being up here. The birds outside the window. The smell of the trees. That money wasn’t the only thing that mattered, that it wasn’t his dad’s fault no one wanted to buy his drawings, that it was OK to eat your dinner without washing your hands first, without a tablecloth, but she refused to listen and sometimes the words were so hard to find that in the end he had given up trying.

To be with his dad.

He raised his eyes to the clouds and hoped they would soon disappear and make way for the stars. Then the fish would come. He shifted his gaze to his father once more, towards his strong arms, which quietly pulled the oars through the almost pitch-black water, and was tempted to tell him that he, too, had been working out and would soon be able to row the boat himself, but he said nothing. He didn’t go to the gym where his mum went – children weren’t allowed and he was only ten years old – but he had worked out at home in his room, push-ups and sit-ups practically every afternoon for almost six months now. He had studied himself in the mirror several times, but his muscles hadn’t grown very much. Never mind, at least he was trying. Next summer, perhaps. By then, the training might have made a difference. The boy with the curly hair had tried to imagine what it would be like. He would walk through the gate with his rucksack, maybe wearing one of the T-shirts the men at his mum’s gym wore, men with big arms, big muscles, who could easily row the boat, and then his dad could sit on the thwart at the back while his son pulled the oars through the water.

‘It’s not a proper fishing trip without a beer.’ His father winked at him while he reached between his legs and opened yet another of the green cans at the bottom of the boat.

The boy nodded back, although he knew this was one of the things his mum had discussed with the visitors, how his dad drank too much and that it was irresponsible. Lake Svarttjønn. The lovely, remote mountain lake which few people knew about, and now the two of them were finally out on it together and so he tried hard not to think about it any more. That his mum had said there wouldn’t be a next time. No more visits to his dad. That this might be the last one.

‘First cast?’ his father whispered, putting the oars in the boat.

‘Fly or spinner?’ the boy whispered back, knowing that this was important, although he had yet to work out why.

His father took another swig of his beer and glanced up at the clouds, then looked across the dark water.

‘What do you think?’

‘Spinner?’ the boy ventured, somewhat hesitantly at first, but he felt his cheeks tingle with happiness when his father nodded and smiled at him and opened the bait box beside him on the thwart.

‘Too dark for a fly, wouldn’t you say?’

‘Yes,’ the boy nodded; he looked up at the clouds and pretended for a moment that he hadn’t noticed the sky wasn’t as starry as it ought to be.

‘Here you go,’ his father said, when he had attached the colourful hook to the end of the fishing line.

It was a solemn moment when the boy took the rod his father was passing to him and, although he knew what his father would say next, he pretended he was learning something new when his father said in a low voice:

‘Keep it short so we don’t hit the bottom, OK?’

‘OK,’ the boy said, and swung the rod over the gunwale.

Hold on tight. Lift the rod. Pull back. Let go at just the right moment. The boy with the curly hair felt flushed with love once more when he saw his father’s eyes, which told him he had done everything right as the colourful hook flew through the air and hit the black water with an almost silent plop.

‘Not too much,’ his father murmured, opening another beer. ‘Easy does it.’

The boy did as his father told him and suddenly felt a strong urge to tell his mum that she was wrong. About the boat. And the lake. He wanted to be with his dad. No matter what the people with the notebooks said. Perhaps he could even move here? Feed the birds? Help his dad fix the roof? Repair the flagstones on the steps, the loose ones? He was so immersed in his thoughts of how wonderful it would be that he nearly forgot he was holding the fishing rod.

‘Bite!’

‘Eh?’

‘You have a bite!’

The boy snapped out of his reverie when he realized that the rod had started to bend. He tried to reel in the line, but he could barely move the handle.

‘It’s a big one!’ the boy burst out, completely forgetting that he was supposed to be quiet.

‘Shit,’ his father said, moving to the back thwart. ‘Your first throw – are you sure you didn’t catch something on the bank?’

‘I . . . don’t . . . think . . . so . . .’ the boy said, reeling in his catch as best he could. It was so heavy it pulled the boat closer to the shore.

‘Here it comes,’ his father said, then grinned and swung his arms over the gunwale. ‘Oh, Jesus!’ he exclaimed.

‘What is it?’

‘Don’t look, Thomas,’ his father cried out as their catch neared the boat.

‘Dad?’

‘Lie down in the bottom of the boat. Don’t look!’

He so desperately wanted to listen, but his ears weren’t working.

‘Dad?’

‘Get down, Thomas, don’t look!’

But he looked anyway.

At the girl lying in the water below them.

Her blue-and-white face.

Her open eyes.

Her floating, wet clothing; clothing completely unsuitable for being out in the forest.

‘Dad?’

‘Lie down, Thomas! For fuck’s sake.’

The little boy didn’t manage to see anything more before his father lunged across the thwart.

And pressed him against the bottom of the boat.

The Boy in the Headlights Samuel Bjork

How can you stop a murderer when you cannot predict their next move? A serial killer is choosing his victims at random, it is a detective's worst nightmare and the ultimate challenge for Munch and Kruger.

Buy now