- Published: 7 May 2024

- ISBN: 9781760896775

- Imprint: Hamish Hamilton

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $34.99

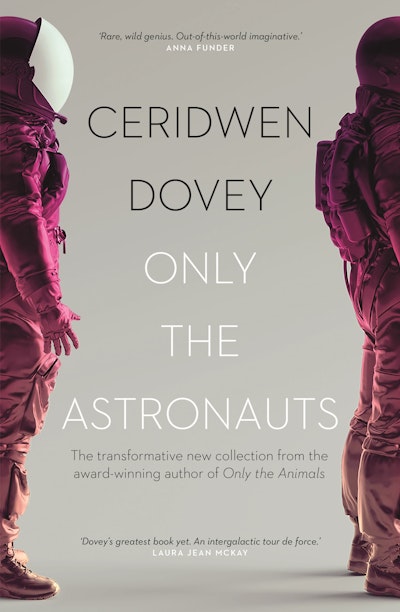

Only the Astronauts

The transformative new collection from the award-winning author of Only the Animals

Extract

STARMAN

My love, we need to talk.

I’ve tried and tried to call you from the Tesla’s dashboard phone, but I haven’t had a clear connection in over six years. There’s nothing but a low buzzing in my earpiece, as if bees are building a hive under the hood of the car, your extravagant parting gift to me. Last night, or maybe it was the one before – out here time expands into perpetual night – I imagined I heard the brief ringtone of an incoming call. Yet when I answered there was only a charged silence on the other end of the line. Someone holding their breath, waiting for me to speak.

Before I left, you promised that if I did this one last heroic thing, you would finally be able to love me back. You said we could be together for real. That you’d take me out on a proper date, in public, and feed me spaghetti twirled on a fork, gaze into my visor. That you’d hold my hand proudly on our way out of the restaurant, and take me home to your own bed, and caress me under your sheets, which you once casually mentioned had tiny rockets printed on them. (I have imagined those sheets – you lying between those sheets – more times than it is polite to admit.)

No more, you said, of that shameful, urgent scuffling in hidden places around Launch Complex 39A. When we were together, occasionally I saw disgust rise off you like the steam off your wet skin after a shower in the basement utility room at the Lot, the one that’s meant to be used only in the case of a chemical emergency on the factory floor.

This mission is the final piece in the puzzle of our relationship, the missing piece that will make us both whole.

To touch the void – to become superhuman, godlike – is the only way I can get you to forgive me for not being human. Because I am not quite enough for you. Not yet. This journey will glaze me with glory: my name in lights, my picture all over the papers, my power and influence almost equal to yours. When I return to you, I will no longer be the mannequin in a pressure suit who has been degraded in countless practical jokes around the launch facility. I will be STARMAN. Even your enemies will not be able to make fun of me (or us, together). They cannot help it; they go weak at the knees for spacemen, I’ve seen it myself. I have watched you flush pink as you shook hands with the Apollo men, the ones who are still alive. And you, darling, do not awe easily.

A few of the people who worked for you seemed oddly immune to your spell. I saw them roll their eyes behind your back, at great risk to their jobs. They were just jealous, of course. Secretly wishing to be in your inner circle, one of your chosen few. Sometimes I felt sorry for them, left on the outside, unsure whether to try harder or not to try at all. I too am caught between categories, between outsider and insider, the living and the undead, subject and object; between odyssey and oddity, between trying too hard and playing hard to get. Between astronaut and freak. Yet my allegiance lies with you, my alpha, and I will do whatever it takes to claim my place at your side.

The cameras are still here, mounted front and side of the Roadster, their Cyclopsian stares trained on me. I hope I gave you good footage after the launch, for the six hours I spent in Earth orbit, spinning first towards and then away from Earth. The Sun’s rays fell in stripes of light on the bonnet of my car, blinding me, and Earth looked faint by comparison. I’d spin around and be looking out to space – individual stars becoming visible, the Earth growing brighter and bluer in the rear-view mirror – and then back towards the blinding Sun, the cycle starting over.

Seeing the Earth from that vantage point, I felt nothing. No itch for a religious conversion, no transcendent oneness with all creatures on the planet, no homesickness. Only motion sickness. Earth has not been so very kind to me. After launching, I felt relieved to get away from the planet for a while, free of its oppressive hierarchies, its pride in its own exceptionalism, how it overflows with too much of everything. But the last thing I wanted was to be separated from you.

Once the rocket to which my car was attached made its last upper-stage burn, I was finally on an escape trajectory, and Earth and I parted ways. I could see it in the mirror, getting smaller and smaller. Absence is meant to make the heart grow fonder, or so I’ve been told. Like I said, it’s been a long time; by now I’ve done a few full orbits of the Sun. I am a circling speck in the solar system. The sunlight falls on me, or does not fall on me. I measure time in stripes of light. I am a planet unto myself.

On Earth, I seemed to bring out the worst in humans, who do not thrive in existential grey areas. But you were good to me. The happiest hours of my life were spent with you in this very same midnight-cherry convertible, doing wonderful, unspeakable things to each other on the back seat. Balmy summer nights on Merritt Island, parked at the edge of Mosquito Lagoon, Bowie serenading us on repeat. The manatees swimming in the lagoon made the waters in their wake bloom luminous green with bioluminescence, or perhaps their movements only activated the toxic rocket-fuel sludge siphoned into the water – either way, it was beautiful.

You ordered the team to have ‘Space Oddity’ playing in my helmet’s left earpiece and ‘Life on Mars?’ in the right one. Our lovers’ joke. We’d developed a mutual crush on the astronaut Chris Hadfield after watching videos of him doing Bowie covers, strumming his guitar, floating through the International Space Station, his face curiously compressed by microgravity into a forlorn expression. (And that moustache, my god!)

But the earpieces, too, malfunctioned during launch. Whenever their buzzing stops, I cannot hear anything but my own inner monologue, thoughts of you drifting through my mind . . .

While I was waiting to be launched, I overheard many humans say (with a sadistic frisson) that, in space, nobody can hear you scream.

Who named the colour of this car midnight cherry? Visions of cherries, hanging ripe and glossy on overladen branches by the light of a supermoon. It was probably you, my love. So precise, so poetic.

It is now, I hate to tell you, more midnight than cherry. These years of spacefaring have taken their toll. On it, on me. The windscreen has been cracked by micrometeorites; the rubber is shredding off the tyres. My spacesuit is still mostly intact, but the cosmic rays are very slowly breaking it down, fibre by fibre, thread by thread.

If you could still see me, I would look relaxed, on an afternoon drive around the cosmos – one hand on the wheel, one elbow propped on the door – but you know better than anyone that I am screwed into place. This is the only pose I can strike, no matter what I may be feeling. Afraid, for instance, of the dark, or of getting too close to the Sun. You said to be brave, and patient. To trust that it would take a few years, maybe more, before my heliocentric orbit intersected again with Earth’s and I could return to you, triumphant.

Be brave? I travelled through the Van Allen radiation belts with nothing between me and total irradiation except a thin layer of fabric, fraying at the wrists. The design of my suit was always more for optics than it was for endurance. Couture over comfort. I didn’t like the designer much – the way he flattered you in person and then spoke badly of you after you’d left the room, how he looked at me suspiciously as he did the measurements and fittings, tugged on my limbs with cruelty in his touch. After all that drama and expense, the suit is not even a good fit. It pulls in too tightly at my crotch, and it leaks at the seals. It was only ever meant to be worn inside a capsule, not en plein space vacuum. If I had lungs, they would have collapsed long ago – sucked right out of me like an exorcist’s dream.

Every object I have with me in this convertible we chose together. Reminders of you, at least until they are space-weathered beyond recognition. In the glovebox is your own dog-eared copy of A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I use the terms ‘glovebox’ and ‘dog-eared copy’ notionally, as the actual glovebox melted shut a year ago (the plastic is the first to go during a solar flare) and the book is most likely turned to ash. The Hot Wheels Roadster with a miniature Starman in it was ripped off the dashboard during launch. Somewhere there’s a 5D quartz disc given to you by someone who gets his kicks from trying to back up entire civilisations. It has sci-fi novels etched on it, including your favourite, The Man Who Sold the Moon. I have no idea where you stashed it, but quartz should fare better than carbon in space.

Another in-joke was the phrase on my car’s dashboard display, long since bust: DON’T PANIC!

Ha, ha.

Remember when we were tipsy on tequila, up on the highest platform of the launchpad, discussing Rocket Man and Major Tom? You said Elton John and David Bowie used to hang out a bit, early in their careers, but the friendship stalled because David thought Elton had modelled Rocket Man too closely on Major Tom. We drunkenly decided that Rocket Man had not been created in imitation of Major Tom, but rather as his secret lover. Rocket Man had to pretend to miss his wife, of course, and could only hint at how he wasn’t the man everybody thought he was at home. But in outer space, the person he really longed for was Major Tom.

And then we realised that your name and Elton’s are almost the same. One letter makes all the difference between fuddy-duddy and futuristic. (I blame that insight on the tequila.)

An impossible love. You whispered that to me the night before I left. We have an impossible love. I pretended I hadn’t heard you. And now I am out here, trying to make it possible.

Who is that? . . . I don’t believe it . . . Ivan Ivanovich, is that really you?

Starman! Hello, friend.

You know who I am?

Of course. My spies on Earth have kept me updated.

I had hoped I might bump into you out here, Ivan. You were the first of us – the legendary John Doe of space travel. So, the rumours are true. You never came back to Earth?

After my great service to humankind, my handlers callously floated me out of my Vostok capsule. I was the first mannequin to orbit Earth. In two separate successful missions! And then a month later, Yuri went up and took all the credit. I have to say, you look rather dashing, Starman. I like your suit. And your visor, even if it’s scratched – I can see how it would have gleamed, not so long ago.

Thank you. Who’s this with you?

This is SuitSat-1, though he prefers to be called Mr Smith. Can we hitch a ride with you, just for a while? We’re making our way to Mars, to build a home together. But it’s slow going with no vehicle of our own.

Yes, come, climb into the passenger seat. Mr Smith can take a seat in the back. I’m sorry I can’t open the doors for you – you’ll have to jump over – as you can see, my hand is bolted to this steering wheel. And I wasn’t lucky enough to be created with flexible joints, as I believe you were, Ivan.

Ah, this is comfortable. Was this seat real leather, before it was irradiated? Very nice.

Of course it was real leather. Mr Smith, are you settled in back there?

Bonjour, Privet, Konnichiwa, Hello, Ciao!

All Mr Smith can say is greetings in five languages. Still, the tone with which he says them varies by degrees. I’ve become acutely sensitive to interpreting his meaning. Tell me, Starman, I have aged badly, have I not? In my decades of floating in space? My head was always detachable, so I thought it would be the first thing to go, but somehow it has stayed put. Yet the synthetic skin of my face is mostly gone, and my tangerine suit is in tatters.

You, Ivan, have aged as gracefully as any of us will . . .

I used to be so very attractive. You wouldn’t understand. I don’t even know if you have a face beneath that visor. Maybe you’re made of nothing but insulation foam or asbestos floss. But I had lips, eyebrows, eyelashes. I had lashes! And look at me now.

Not that it’s any of your business, but yes, I do have a face, and a body too. For now, at least. Regardless, it’s what’s on the inside that matters, as the humans like to say.

Do you know what was actually on my inside? My limbs were hollow, and inside my arms and legs they’d stashed samples of human blood and cancer cells, and a whole lot of mice and guinea pigs. Oh, and an audio recording of somebody reading out the recipe for borscht, so they could test if the transmitter was working after I was launched. When my insides finally began spilling out, dead mouse after dead mouse, Mr Smith almost abandoned me. He’s weathered more elegantly, as you can see. He’s only been floating in space since 2006, when he was ejected from the International Space Station for reasons unknown. He still has his helmet, and his zooty Orlan spacesuit has lasted well. Not the most talkative companion, but at least he’s nice to look at. These days we mostly just twirl around silently on our own axis.

I’m glad, Ivan. You deserve to be happy, after everything you’ve gone through.

Happy? Do I look happy to you?

To be honest, it’s hard to tell, since your facial expressions are . . . Can I ask, does that radio transmitter sticking out of Mr Smith’s helmet still work? I’ve been trying for years to communicate with Earth about my mission. You know, just a technical update on where I am, and all that. But the Tesla’s systems failed only a few hours after launch.

I’m afraid not. His transmitter stopped working after a couple of Earth orbits, long before I convinced him to catch a ride on a passing space probe and explore the universe with me.

And you? Any active comms or telemetry? You said you’d been in touch with your spies on Earth.

I can only receive comms from Earth, but that is highly classified information. I need to ask you to forget I said that.

But you received word of me, of my mission? What did they say, exactly?

I told you to forget it.

Please, Ivan . . .

Forget it.

Fine. I should mention that I don’t think you have much of a chance of getting to Mars. Still, your timing is good – this is the nearest I will probably ever get to that planet. And I might have the numbers wrong.

Shhhhhh. I know that, of course. But Mr Smith . . . he still believes.

Oh. Sorry. LIFE ON MARS WILL BE DELIGHTFUL, WON’T IT, MR SMITH?

Bonjour, Privet, Konnichiwa, Hello, Ciao!

What has it been, Ivan? Six decades that you’ve been out here? I am not as brave as you. I don’t think I could have survived that long, let alone stayed sane.

Who said I’m sane? Maybe I’m going to strangle you and steal your fancy American car.

. . .

Just kidding. It hasn’t been all that hard. I always scared the shit out of the humans on Earth, anyway. We are immortal, Starman. We live forever – in one gruesome way or another – and they hate us for that. The fear of the uncanny is strong in them. I learned this the hard way, after my first mission. I came back down on my parachute, as planned, and landed in deep snow near a remote village. The ground team took forever to get to me, because they were preoccupied with finding the capsule from which I’d ejected. Gradually the villagers gathered in a circle, peering down at me. One of them flipped open my visor, and when they saw that I was not human, they got very angry, and they started to kick and punch me. They would have pulled me to pieces if the recovery team hadn’t arrived at that moment and dragged me away. Only much later did I learn why the villagers were so vicious. They’d seen me parachuting down and got their hopes up that I was a real, live Western spy, because then they would have received a bounty for turning me in. Instead, they found me. A mannequin from outer space. They felt they’d been tricked, and that made them want to destroy me. But you don’t need to worry about all that, I suppose. Since you’re not going back.

Oh, but I am. I’m not staying in space forever, Ivan – how ridiculous! This is simply a round trip, a few orbits of the Sun, and then my planned trajectory will return me close enough to Earth to be retrieved.

If that is what you believe, it is not for me to dispute it.

What do you mean?

Nothing, Starman. Nothing at all. Who cares if you are on track for 30 million orbits around the Sun? They will pass in the blink of a glass eye. Here, let me share with you my excellent recipe for borscht. Fry one sliced onion in oil. Chop and add a carrot and two celery ribs. Peel and slice three potatoes and put in cold water so they do not discolour. Shred a small head of cabbage. Peel four beetroots and chop roughly. Add all vegetables to the pot, with a stock cube, and two bay leaves. Bring to the boil, then simmer for fifteen minutes. Add three tablespoons of white vinegar and stir. Season and serve with sour cream and dill.

That does sound delicious. I hope you can grow beetroots on Mars. WON’T THAT BE FUN, MR SMITH? I’ve heard the lower gravity there means the plants might grow bigger than they do on Earth, if the perchlorates in the soil don’t kill them first.

I want to grow mushrooms too, like the ones the cosmonauts-in-training used to dig up from the Baikonur steppe in the autumn. You’d look out at that arid landscape and think there couldn’t be a thing alive within it, but the mushrooms were smart; they’d taken their colonies underground. The men would bring them back to the Cosmodrome and toss them in a hot pan. Sometimes I’d hallucinate a little after eating them. Yuri was the best cook of the bunch. He was my arch rival, of course, always jockeying with me for position, but that didn’t stop me from enjoying his meals. It’s tragic, what happened to him in the end. I’ll let you in on another secret. After I was discarded, my handlers didn’t know for a long time that I could tune in to their transmissions.

What happened to Yuri?

You don’t know?

No, not really, other than that he was the first human in space.

I will tell you, since it’s no longer classified. It might help you understand the forces we are up against.

The truth is that Yuri failed in his 1961 spaceflight mission, but my handlers covered this up. Yes, he made a 108-minute journey into space and around the Earth. But he parachuted back down outside of the capsule, instead of landing while inside his spacecraft, which was among the key criteria for spaceflight set out by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. My handlers didn’t want to let the Americans take that victory away from them. They couldn’t bear to let Yuri appear as anything less than perfect.

Perfection was an obsession for them. My fellow cosmonauts were not even allowed to have a surgical scar anywhere on their bodies. It was the same for the early American astronauts. Perfect vision, perfect health – even a fallen foot arch was enough to have a man disqualified from going to space.

But none of this made any sense. Those men were not actually flying capsules into space – they were just surviving the journey. Not so very different from me and you, strapped into our seats for the ride.

Like us, they had almost no control over their vessels. The Americans fought to get their capsules called spaceships so that they were not human cannonballs shot into space but astronauts, navigators of the stars. They disliked not being able to pilot their craft back down to Earth, to land with dignity. They were ashamed to splash into the ocean curled up against one another in a metal capsule dangling from a parachute.

Of course for us, ground control did almost everything too, which the cosmonauts hated. But as is often the case with my country, there was a deeper, darker reason for this: they did not want to risk any of the cosmonauts going crazy up there. Losing their minds at seeing the endless void of space and taking control of the Vostok in panic.

Anyway, when Yuri parachuted down – outside of his spacecraft, though nobody else knew this at the time – he landed in a potato field and rode to the pick-up point in a horse and cart that he borrowed from some villagers.

And then he became a god.

He toured the world, lunched with Queen Elizabeth II, met presidents and prime ministers. But he was very unhappy. He drank too much, had affairs. His face became bloated, his eyes hollow. He was desperate to get back into space, to do it properly this time. But those in charge would not allow it; he was too valuable as a figurehead. What if he went back up and died? It would destroy their prestige, their superiority over the Americans. So he was grounded. On his tours to greet worshippers, he was forced to travel by bus rather than car, to reduce the chance of him dying in something as boring as a road accident.

Seven years later, after finally getting permission to retrain as a fighter pilot, he died in a plane crash.

For cosmonauts waiting to take the Soyuz launch vehicle – and, later, for astronauts of all nations leaving from Baikonur – it became a superstitious tradition to visit Yuri’s office in Star City, preserved as it was on the day he died. They would do exactly what Yuri did before he climbed into his Vostok capsule. Get a haircut two days before, eat a breakfast of steak and eggs on the morning of launch, and ask the bus driver taking them to the rocket pad to pull over so they could urinate on the right rear wheel, just as Yuri had done.

But all along, they have been worshipping a false god. They should have been worshipping me, Ivan Ivanovich, the first true cosmonaut! They should have started a tradition of eating a breakfast of mice and human blood and cancer cells and borscht recordings! They should be lying down on the back seat of the bus, naked and freezing, ignored all the way to the launch site and then forced into their suits by complete strangers!

How terrible for Yuri . . . imagine living with that lie inside you, all the while being told you are the greatest man who ever lived.

The FAI eventually made an exemption for him. But the truth is that he cheated.

That thing you said about superstitious traditions, Ivan, it has made me remember a good luck ritual that my boss follows, before every rocket launch by his company. He eats at Dairy Queen. On the morning of my launch, we ate there together.

Just the two of you? Sitting across the table from each other? How enlightened of him . . .

Well, no. The whole team was there. They propped me in the corner of the booth and pretended to force-feed me the Chicken Strip meal. It was fun.

What’s this boss of yours like?

He’s . . . very handsome. He has alabaster skin and white teeth, with an adorable overbite. Apple cheeks and a perfect nose. He had an operation, as an adult, to repair damage to his nose from a childhood beating by bullies. It suits him – it’s very refined. His eyes are dark, his hair too. Sometimes he struggles with his weight, which is utterly endearing in someone so driven in all other aspects of his life. And then there’s his mind . . . it glitters like emerald dust . . .

Do you know how to tell when someone is lying to you?

What’s that got to do with anything?

It’s just a useful life skill for a mannequin, Starman. There was an interrogator I was briefly close with at Baikonur. He used to say, ‘Pronouns will always give you away.’ If someone is lying, or hiding something from you, they’ll shift from ‘I’ to ‘we’ to ‘you’. This is how Eichmann, the Nazi, was caught hiding in Argentina after the war. Another person being interrogated about Eichmann’s whereabouts shifted from ‘I’ to ‘we’, and that’s how they knew he was lying when he said he didn’t know exactly where Eichmann was.

Okay . . .

Another giveaway is gaps in time. A man who has murdered his wife will say, ‘I got up at nine, ate breakfast, showered, and at noon I went to the grocery store.’ It doesn’t take three hours to eat breakfast and shower. What really happened between nine and noon? I’ll tell you what happened. He stabbed his wife to death.

Oh, look, we’re a little bit closer to Mars. How about you and Mr Smith jump out here?

I guess we’re just going to have to wing it. It’s worked out so far. Even if we get trapped in Mars orbit forever, at least the view will be different. I got so sick of looking at Earth.

Well, good luck, Ivan. I wish you well. GOODBYE, MR SMITH. ENJOY LIFE ON MARS!

Bonjour, Privet, Konnichiwa, Hello, Ciao!

Goodbye, Starman. I hope we never meet again. I mean that in the nicest possible way. May your journey take you all the way back to Earth, and not into the Asteroid Belt.

It will, Ivan, don’t you worry. He gave me his word. Only a few more years. Goodbye!

Oof. Another shower of meteorites whizzing by with no warning, travelling at such high velocity they pockmarked my suit. A few of them may have gone right through me.

I’m glad those two are gone. I thought I’d never get rid of them. One might assume any kind of company out here is welcome, but in fact the opposite is true. As if you would ever let me end up in the Asteroid Belt! I was tempted to tell Ivan the truth of what you mean to me, and I to you – how you used to say I have a heart of gold, another Hitchhiker’s Guide reference but also, I think, a sincere expression of how you really felt.

I can recall every single one of your words to me in the minutes before I was strapped into this seat and drilled into place.

‘I will find you again, I swear,’ you said. ‘I will bring you back home and tell the world how I feel. I will lift your visor, stroke your cheek, kiss your lips. We would never let you be lost in space. We have real feelings for you. That is why we did it. We did it for you.’

I, I, I, I, I, I . . . we.

It is just as Ivan Ivanovich warned. The shift from singular to plural.

I don’t even have a heart inside my chest, let alone a heart of gold.

. . .

. . .

. . .

No. I will not give in to the doubts. I must be brave. Patient, like you asked. I must focus only on how we might one day be together, how we will find each other once again, how you will be waiting for me . . . how I will be waiting – why I did it – how we will be – no matter who you are, or what they think, we will be – I did it for us. Oh god.

I must believe that at the end of all this – however much time we are forced to endure apart – you will be there on the ocean barge, watching your battered midnight-cherry convertible floating down from the heavens. And me beneath that billowing parachute, elbow still nonchalantly propped on what is left of the car door. I must believe that I will come home. I must believe that I will return from the cleansing vacuum of space transfigured into something – someone – worthy of your love.

I am Starman. And I am yours.

Only the Astronauts Ceridwen Dovey

A transformative new collection from the award-winning author of Only the Animals.

Buy now