- Published: 2 November 2021

- ISBN: 9781529112894

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 272

- RRP: $24.99

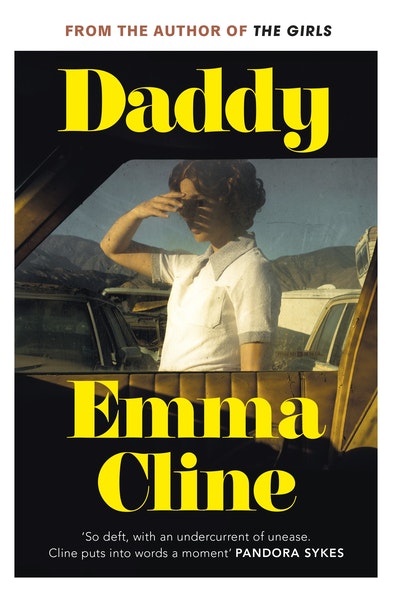

Daddy

Extract

WHAT CAN YOU DO WITH A GENERAL

LINDA WAS INSIDE, ON HER PHONE—TO WHO, THIS EARLY? From the hot tub, John watched her pace in her robe and an old swimsuit in a faded tropical print that probably belonged to one of the girls. It was nice to drift a little in the water, to glide to the other side of the tub, holding his coffee above the waterline, the jets churning away. The fig tree was bare, had been for a month now, but the persimmon trees were full. The kids should bake cookies when they get here, he thought, persimmon cookies. Wasn’t that what Linda used to make, when the kids were little? Or what else—jam, maybe? All this fruit going to waste, it was disgusting. He’d get the yard guy to pick a few crates of persimmons before the kids came, so that all they’d have to do was bake them. Linda would know where to find the recipe.

The screen door banged. Linda folded her robe, climbed into the hot tub.

“Sasha’s flight’s delayed.”

“Till?”

“Probably won’t land until four or five.”

Holiday traffic would be a nightmare then, coming back from the airport—an hour there, then two hours back, if not more. Sasha didn’t have her license, couldn’t rent a car, not that she would think to offer.

“And she said Andrew’s not coming,” Linda said, making a face. Linda was convinced that Sasha’s boyfriend was married, though she’d never brought it up with Sasha.

Linda fished a leaf out of the water and flicked it into the yard, then settled in with the book she’d brought. Linda read a lot: She read books about angels and saints and rich white women from the past with eccentric habits. She read books by the mothers of school shooters and books by healers who said that cancer was really a self-love problem. Now it was a memoir by a girl who’d been kidnapped at the age of eleven. Held in a backyard shed for almost ten years.

“Her teeth were in good shape,” Linda said. “Considering. She says she scraped her teeth every night with her fingernails. Then he finally gave her a toothbrush.”

“Jesus,” John said, what seemed like the right response, but Linda was already back to her book, bobbing peacefully. When the jets turned off, John waded over in silence to turn them on again.

Sam was the first of the kids to arrive, driving up from Milpitas in the certified pre-owned sedan he had purchased the summer before. He had called multiple times before buying the car to weigh the pros and cons—the mileage on this used model versus leasing a newer one and how soon Audis needed servicing—and it amazed John that Linda had time for this, their thirty-year-old son’s car frettings, but she always took his calls, going into the other room and leaving John wherever he was, alone with whatever he was doing. Lately John had started watching a television show about two older women living together, one uptight, the other a free spirit. The good thing was that there seemed to be an infinite number of episodes, an endless accounting of their mild travails in an unnamed beach town. Time didn’t seem to apply to these women, as if they were already dead, though he supposed the show was meant to take place in Santa Barbara.

Chloe arrived next, down from Sacramento, and she had driven, she said, at least half an hour with the gas light on. Maybe longer. She was doing an internship. Unpaid, naturally. They still covered her rent; she was the youngest.

“Where’d you fill up?”

“I didn’t yet,” she said. “I’ll do it later.”

“You should’ve stopped,” John said. “It’s dangerous to drive on empty. And your front tire is almost flat,” he went on, but Chloe wasn’t listening. She was already on her knees in the gravel driveway, clutching tight to the dog.

“Oh, my little honey,” she said, her glasses fogged up, holding Zero to her chest. “Little dear.”

Zero was always shivering, which one of the kids had looked up and said was normal for Jack Russells, but it still unnerved John.

LINDA WENT TO PICK UP Sasha because John wasn’t supposed to drive long distances with his back—sitting made it spasm—and, anyway, Linda said she was happy to do it. Happy to get a little time alone with Sasha. Zero tried to follow Linda to the car, bumping against her legs.

“He can’t be out without a leash,” Linda said. “Be gentle with him, okay?”

John found the leash, careful, when he clipped it to the harness, to avoid touching Zero’s raised stitches. They looked spidery, sinister. Zero was breathing hard. For another five weeks, they were supposed to make sure he didn’t roll over, didn’t jump, didn’t run. He had to be on a leash whenever he went outside, had to be accompanied at all times. Otherwise the pacemaker might get knocked loose. John hadn’t known dogs could get pacemakers, didn’t even like dogs inside the house. Now here he was, shuffling after Zero while he sniffed one tree, then another.

Zero limped slowly to the fence line, stood still for a moment, then kept going. It was two acres, the backyard, big enough that you felt insulated from the neighbors, though one of them had called the police once, because of the dog’s barking. These people, up in one another’s business, trying to control barking dogs. Zero stopped to consider a deflated soccer ball, so old it looked fossilized, then kept moving. Finally he squatted, miserable, looking back at John as he took a creamy little shit. It was a startling, unnatural green.

Inside the animal was some unseen machinery keeping him alive, keeping his animal heart pumping. Robot dog, John crooned to himself, kicking dirt over the shit.

Four o’clock. Sasha’s plane would just be landing, Linda circling arrivals. It was not too early for a glass of wine.

“Chloe? Are you interested?”

She was not. “I’m applying to jobs,” she said, cross-legged on her bed. “See?” She turned the laptop toward him for a moment, some document up on the screen, though he heard a TV show playing in the background. She still seemed like a teenager, though she’d graduated college almost two years ago. At her age, John had already been working for Mike, had his own crew by the time he was thirty. He was thirty when Sam was born. Now kids got a whole extra decade to do—what? Float around, do these internships.

He tried again. “Are you sure? We can sit outside, it’s not bad.”

Chloe didn’t look up from the laptop. “Can you close the door,” she said, tonelessly.

Sometimes their rudeness left him breathless.

He put together a snack for himself. Shards of cheese, cutting around the mold. Salami. The last of the olives, shriveled in their brine. He took his paper plate outside and sat in one of the patio chairs. The cushions felt damp, probably rotting from the inside. He wore his jeans, his white socks, his white sneakers, a knitted sweater—Linda’s—that seemed laughably and obviously a woman’s. He didn’t worry about that anymore, how silly he might look. Who would care? Zero came to sniff his hand; he fed him a piece of salami. When the dog was calm, quiet, he wasn’t so bad. He should put Zero’s leash on, but it was inside, and, anyway, Zero seemed mellow, no danger of him running around. The backyard was green, winter green. There was a fire pit under the big oak tree which one of the kids had dug in high school and ringed with rocks, but now it was filled with leaves and trash. Probably Sam, he thought, and shouldn’t Sam clean it up, clean all this up? Anger lit him up suddenly, then passed just as quickly. What was he going to do, yell at him? The kids just laughed now if he got angry. Another piece of salami for Zero, a piece for himself. It was cold and tasted like the refrigerator, like the plastic tray it had come on. Zero stared at him with those marble eyes, exhaling his hungry, meaty breath until John shooed him away.

Even accounting for holiday traffic, Linda and Sasha got back later than he expected. He went out onto the porch when he heard their car. He’d had the yard guy put up holiday lights along the fence, along the roof, around the windows. They were these new LED ones, chilly strands of white light dripping off the eaves. It looked nice now, in the first blue dark, but he missed the colored lights of his childhood, those cartoonish bulbs. Red, blue, orange, green. Probably they were toxic.

Sasha opened the passenger door, a purse and an empty water bottle on her lap.

“The airline lost my suitcase,” she said. “Sorry, I’m just annoyed. Hi, Dad.”

She hugged him with one arm. She looked a little sad, a little fatter than the last time he’d seen her. She was wearing some unflattering style of pant, wide at the legs, and her cheeks were sweating under too much makeup.

“Did you talk to someone?”

“It’s fine,” she said. “I mean, yeah, I left my information and stuff. I got a claim number, some website. They’re never going to find it, I’m sure.”

“We’ll see,” Linda said. “They reimburse you, you know.”

“How was traffic?” John asked.

“Backed up all the way to 101,” Linda said. “Ridiculous.”

If there were luggage, at least he would have something to do with his hands. He gestured in the direction of the driveway, the darkness beyond the porch light.

“Well,” he said, “now everyone’s here.”

“IT’S BETTER THIS WAY,” Sam said. “Isn’t it better?”

Sam was in the kitchen, connecting Linda’s iPad to a speaker he’d brought. “Now you can play any music you want.”

“But isn’t it broken?” Linda said from the stove. “The iPad? Ask your dad, he knows.”

“It’s just out of batteries,” Sam said. “See? Just plug it in like this.” The counter was cluttered—John’s secretary, Margaret, had dropped off a plate of Rocky Road fudge covered in Saran wrap, and old clients had sent a tin of macadamia nuts and a basket of fig spreads that would join the fig spreads from years past, dusty and unopened in the pantry. Lemons in a basket from the trees along the fence line, so many lemons. They should do something with the lemons. At least give some to the yard guy to take home. Chloe was sitting on one of the stools, opening Christmas cards, Zero at her feet.

“Who are these people, anyway?” Chloe held up a card. A photograph of three smiling blond boys in jeans and denim shirts. “They look religious.”

“That’s your cousin’s kids,” John said, taking the card. “Haley’s boys. They’re very nice.”

“I didn’t say they weren’t nice.”

“Very smart kids.” They had been good boys, the afternoon they visited, the youngest laughing in a crazy way when John dangled him upside down by his ankles.

Linda said that John was being too rough, her voice getting high, whiny. She got worried so easily. He loves it, John said. And it was true: when he righted the boy, his cheeks red, his eyes wild, he’d asked to go again.

Sasha came downstairs: her face was wet from washing, some sulfurous lotion dabbed on her chin. She looked sleepy, unhappy in borrowed sweatpants and a sweatshirt from the college Chloe had gone to. Linda talked to Sam every day, Chloe, too, and saw them often enough, but Sasha hadn’t been home since March. Linda was happy, John could tell, happy to have the kids there, everyone in one place.

John announced that it was time for a drink. “Everyone? Yes?” he said. “I think let’s do a white.”

“What do you want to listen to?” Sam said, controlling the iPad with a finger. “Mom? Any song.”

“Christmas songs,” Chloe said. “Put on a Christmas station.”

Sam ignored her. “Mom?”

“I liked the CD player,” Linda said. “I knew how to use it.”

“But you can have everything that was on your CDs, and even more,” Sam said. “Anything.”

“Just pick something and play it,” Sasha said. “Christ.”

A commercial blared.

“If you subscribe,” Sam said, “then there won’t be any commercials.”

“Come on,” Sasha said. “They don’t want to deal with that stuff.”

Sam, wounded, turned the volume down, studied the iPad in silence. Linda said that she loved the speaker, thank you for setting it up, wasn’t it nice how it freed up all this counter space, and dinner was ready anyway so they could just turn the music off.

Daddy Emma Cline

The stories in Emma Cline's stunning first collection consider the dark corners of human experience, exploring the fault lines of power between men and women, parents and children, past and present.

Buy now