- Published: 14 March 2023

- ISBN: 9781405949651

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 464

- RRP: $24.99

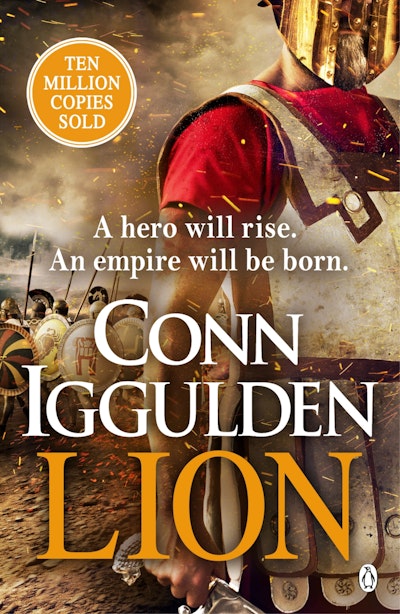

Lion

Extract

Prologue

Pausanias took a deep breath, feeling calm spread through him. He exchanged a glance with his soothsayer, then rose from kneeling to walk the length of the hall, for once completely alone. The royal chamber of Sparta was cool after the heat of the morning. His armour clinked and rattled as he strode down the central aisle. He was unwounded, thanks to Ares and Apollo, his patron gods. He would endure no crippling disfigurement, no fever to steal away his wits. In the prime of his youth, he had already recovered from the hardships of the campaign. Of course, victory had a way of reducing aches and hungers. Only those who lost a great battle had to endure exhaustion. Those who won often discovered they could dance and drink enough for two.

Pausanias was pleased he had managed to bathe before the summons. His hair was damp and he felt cool despite the heat. Yet he had not been long back in Sparta. His personal helots had still been cleaning his cloak when the runner came. Most of the dried blood and dust had been brushed out, as well as lines of salt his sweat had left behind. It would do. He draped a length of it over his shoulder as he walked, held with an iron clasp.

When he had first immersed himself in the cold pool, Pausanias had watched a skin of oily filth moving away from him over the water. He still hoped it was a good omen. He had looked up from strange patterns and suddenly seen the red eyes of his helots, their trembling hands. He understood then, as he had not before. They grieved.

He might have dismissed them for intruding on his thoughts; he had not. They too had fought at Plataea, losing thousands of their number against Persian infantry. It had been a kind of madness and he still blamed the Athenians for inspiring them. Pausanias had warned Aristides not to let slaves think they were men!

As he walked down the long nave, he thought the helots would not need to be culled that year. In normal times, when they grew too numerous, young Spartans would hunt them through the streets and into the hills, competing for kills and trophies. Yet as he had leaned back in the pool, he thought he’d seen something new in their eyes, something troubling. For just a moment, he thought they looked on him as wild dogs might look on an injured deer.

He shook his head. Perhaps he would order a cull after all, to remind them of their place. Curse Aristides! Helots were too numerous ever to be free. It was a knife-edge Sparta chose to walk – the constant threat that kept them strong

He caught himself in his thoughts. He would not order any cull. His authority had ended the moment he crossed back into Spartan territory. No, it would be the man who had summoned him who would make decisions of that sort.

When he reached the end of the hall, Pausanias dropped to one knee, staring at polished stone. He was somehow not surprised when silence stretched. The younger man wished him to understand which of them held power in that place. Pausanias told himself to be cautious. There was more than one kind of battlefield.

‘Stand, Pausanias,’ Pleistarchus said at last.

The young king was still a month from his eighteenth birthday, but the fact that he was a son of Leonidas could be seen in the massive forearms, thick with black hair. Pleistarchus had wanted desperately to command at Plataea, but the ephors of Sparta had forbidden it. They had already lost their battle king at Thermopylae. His son was the most precious resource Sparta had.

Instead, it had been Pausanias who led the army of Sparta, standing in as the king’s regent. It had been he who won an extraordinary, impossible victory, ending the great invasion and breaking at last the dreams of Persian kings.

Pausanias swallowed, suddenly weary. His triumph had earned him no goodwill, he could see that. He raised his head and met the cold gaze of the king. At least whatever was coming would be quick. Athenians seemed to be three-quarters wind for all the talking they did. His own people spent words with more care.

‘You have done your duty,’ Pleistarchus said. Pausanias bowed his head in response. It was enough, and still more than the young king wanted to say. Two of the ephors nodded, expressing their support. It mattered more that three did not. They only watched the man who had led every Spartiate and helot to victory.

‘I will present the names of the honoured dead,’ Pausanias said into the silence. The helots would not be listed, of course, only Spartan warriors who had fallen. With the blessing of Apollo and Ares, they at least were few.

Pausanias tried to resist the fierce pride that rose in him then, despite the formal words. He had been part of that extraordinary day! He had held back men in dust and chaos, until it had been time to put them in, as a golden stone in the flood, to stand against the Persian generals. The ephors had not been there then. The son of Leonidas had not been there!

Pausanias felt a weight settle upon his shoulders. That was exactly the problem they faced, the reason they stared as if they wished to open him up like a fruit and examine his entrails. The ephors had forbidden Pleistarchus from leaving Sparta – and in doing so, denied him the greatest victory in the history of the city-state. The young king must hate them for it, or perhaps . . . Pausanias felt his mouth grow dry. He had been called alone to that place. Only because the soothsayer had been with him had the other man come. Would either of them be allowed to leave alive? He tried to swallow. The heart of Sparta was in peitharchia – total obedience. This son of Leonidas had endured utter misery, watching his father’s army taken to war by someone else. He had not made a word of complaint, Pausanias recalled. It spoke rather well for the sort of king he would be.

‘I have been deciding what to do with you,’ Pleistarchus said.

Pausanias felt cold steal into him. If the young king ordered his death, he would not leave that room. By his own hand or another’s, his life was in the hands of a youth who resented him, in the hands of ephors who regretted the battle that had saved them all. Win or lose, it seemed there had been no way back. Sensing his life hung in the balance, Pausanias spoke quickly.

‘Majesty, ephors, I would like to visit the oracle at Delphi, to learn what lies ahead.’

It was well judged. Even the ephors of Sparta would not ignore a request to speak to Apollo’s own representative. The Pythian priestess sat above steam from the underworld and spoke with the voice of the god. Pausanias felt his heart leap as two of the ephors exchanged a glance.

King Pleistarchus shook his head, frowning.

‘Perhaps you will, when duty allows. Until then, I called you here this evening to give you command of the fleet, Pausanias. King Leotychides and I are in agreement. You will take our authority amongst the cities and their ships. There are Persian strongholds still. They cannot be allowed to rebuild or grow strong once again. Sparta leads, general. So lead – far from here.’

The message behind the last was clear enough. Pausanias felt relief flood through him. He had swung from pride to dread and back, and he felt himself flush as his heart thumped. It was a fine solution. The victor of Plataea would go far away from the young king who actually ruled the armed forces of Sparta. There would be no awkward clash of loyalties, no chance of civil war. Men revered those who led them, Pausanias knew very well. In that moment, he might have flung the entire army against the ephors. They had to fear him. He thought he saw it in their eyes, in the way they watched. Yet he was obedient.

He knelt once more.

‘You honour me, Majesty,’ he said. He was pleased to see Pleistarchus smile. He must have been worried about his battle-hardened general returning with victory under his belt.

‘It is more than a reward for service, Pausanias,’ the young king said. ‘Athens seeks to rule at sea, as we rule on land. They have been gathering at Delos, but I do not want them leading our allies. Sparta is first among the Hellenes and always will be. You will take six ships to them, with a full complement of Spartiates and helot rowers. Your authority is given by my hand to remind them of that. You will lead the allied fleet, do you understand?’

‘I do, Majesty,’ Pausanias said. He could feel his skin twitch, hairs rising. He wondered how the Athenians would feel about that.

He rose to his feet and was pleased when the young king held him by both shoulders, then kissed him on each cheek. It was a mark of royal approval and it meant he would survive. He felt himself tremble in reaction, sweat making his skin shine.

‘Your ships are in port by Argos, Pausanias. Summon whomever you wish as your officers. I leave that to your discretion.’

Pausanias bowed in reply. Of course. The young king sought to rid himself of anyone else who might support Pausanias over his own right to rule. Pausanias forced himself into cool praotes – the perfect calm of Spartan men. He took the king’s hand in his own and raised it over his head.

‘You have served Sparta well,’ an ephor said.

It was not one of those who had shown any support for him, Pausanias noted. Even so, he bowed deeper. The five old men spoke for the gods and kings of Sparta, after all.

Pausanias strode back down the long nave, his head high. He saw Tisamenus waiting for him there, both eyebrows raised in question. The soothsayer was not sure what mood Pausanias was in after whatever he had been told.

Pausanias clapped him on the shoulder as he passed, allowing himself a tight smile.

‘Come on, my friend, we have a lot to do.’

‘You’re pleased, then?’ Tisamenus asked.

Pausanias thought for a moment and nodded.

‘Yes. It’s good news. They have given me the fleet!’

Lion Conn Iggulden

Discover the rise and fall of the world's greatest empire in the stunning first instalment of The Golden Age, an epic new series from the nation's finest historical novelist

Buy now