- Published: 16 April 2020

- ISBN: 9781473572553

- Imprint: Cornerstone Digital

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 416

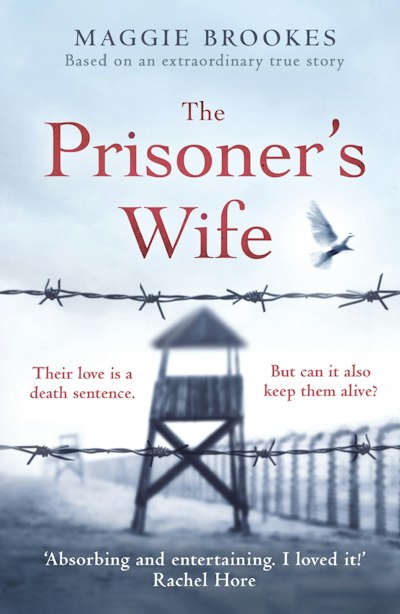

The Prisoner's Wife

based on an inspiring true story

Extract

This story starts in the Czech region of Silesia, which had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918. Many of the people who lived there were German -speaking and welcomed the Nazi annexation of their lands. However, in March 1939 Hitler rode into Prague, declaring the rest of Czechoslovakia a ‘protectorate’ of the Third Reich, and the entire country began life under the Nazis. By 1944 Czech resistance was becoming strong.

The names of many places have changed since 1944. This novel uses a mix of modern and wartime names. For more information about this, see the Author’s Note on page 397.

Prologue

Everything was quiet and still, apart from the light crunch of our boots as we crept down the deserted street. The sliver of moon disappeared behind a cloud and we slowed our pace, barely able to make out the way ahead.

That was when we heard the dogs. Only one bark at first, carrying in the quiet of the night. We clutched each other’s hands and stood still for a moment.

Then another bark. And another. Not muffled by the walls of a building, but out in the night, like us, out in the streets.

Instinctively we moved away from the sound, and the buildings glowered at us, closing in. My heart was drumming and my breath came fast. We walked more quickly. The dogs were barking, closer, echoing off the buildings – perhaps two of them, perhaps three. We turned to see if they were in sight, but the darkness was too absolute. We were acutely aware of the noise of our boots on the cobbled road.

And then there were shouts behind us: men’s voices, excited to have something to do in the boredom of the night-watch, egging on the dogs, eager for the hunt. Whichever way we turned, the dogs and the men grew closer and our boots clanged louder.

It became a town of sounds: our breath, the pounding of our own blood in our ears, the clatter of our boots on the road, the dogs barking, men running and calling, closer, closer. Perhaps we could have stopped, knocked on a door and begged for help, but we didn’t. We just kept going, faster and faster, running, Bill dragging me with him. I was breathless to keep up, my kit-bag banging awkwardly against my legs.

At last there was an opening in the terrace, an archway leading into a narrow arcade lined with dark shops. Towards the end of the alley was an even darker place that looked like another turning, but it was only a wide doorway, up two steps, set back and hidden until we drew level with it.

Now the dogs were almost upon us, and Bill pulled me up into the doorway, threw his arms around me, squeezed me very hard and whispered, ‘I’m so sorry’ into my hair. Then he pushed me away from him, so we wouldn’t be found touching. I shut my eyes and waited for the dogs’ teeth, hoped it would be over quickly.

Everything seemed to happen at once: the dogs, the men, a searchlight in my face. I raised my arm to cover my eyes and heard the panting breath of the men, the loudness of their voices. My teeth were chattering and I had to clamp them shut. The voices behind the light became one disembodied shout in German from the senior officer. ‘Hands up! Against the wall!’

We stumbled down the two steps. Bill went to one side of the doorway, and I to the other. I raised my hands and leaned my face against the wall to stop myself from falling, feeling the roughness of the brick against my cheek.

Behind the wall I sensed the people who lived there scurrying like mice, listening with excitement and maybe – who knows? – with pity. I bit my lips, determined not to sob, not to let it end this way.

PART ONE

VRAŽNÉ, OCCUPIED CZECHOSLOVAKIA

June to October 1944

1

War had ripped across Europe for five years – a great tornado, scattering families, tearing millions of people from their loved ones for ever. But sometimes, just sometimes, it threw them together. Like me and Bill. A Czech farm girl and a London boy who would never have met, were hurled into each other’s paths. And we reached out, caught hold and gripped each other tight.

We had the Oily Captain to thank for bringing us together. I always thought of him as the Oily Captain because there was something too eager to please in his manner that made me despise him. Although he was a Nazi officer, he was nothing like the bands of SS who descended without warning to search the farm and interrogate us about my father and older brother, Jan.

We knew at once that the Oily Captain was different, because the first day he turned up at the farm he even knocked at the back door before he pushed it open. He stood silhouetted in the door frame, stocky and well fed on ‘requisitioned’ farm produce.

My mother was by the sink, cutting potatoes. She dropped a potato in the water and turned, keeping the knife in her right hand. In one glance he took in the kitchen – the knife, my mother in her apron, me with my books spread out on the table, and Marek playing on the floor.

‘Do you speak German?’ he asked her politely, although most people in our region spoke nothing else.

‘Of course,’ my mother replied in her impeccable High German accent, brushing a wisp of hair from her eyes with the back of her left hand. I nodded too, imperceptibly.

His face brightened. ‘May I come in?’

My mother made a small flick of her fingers, which meant ‘Can I stop you?’ and he took a step forward.

She rested her knife-hand on the edge of the sink and frowned at the mud he’d walked onto her clean floor. My little brother Marek stood up. He was only eight, but took his position as man of the house very seriously.

The captain removed his hat. Beneath it his hair was short and peppered with grey. He had the open face of a countryman used to looking at the sky. His lips were thin and maybe mean, but the wrinkles around his eyes spoke of someone who liked to laugh. He seemed older with his hat off.

‘I’ve been looking over your farm . . .’ My mother’s face darkened, and he waved his innocence. ‘I want to offer you some help to bring in the crops.’

Only so that you can confiscate them, I thought, and knew my mother was thinking the same. They requisitioned every turnip, every bushel of oats, every ham we produced.

‘I’ve got a working party of prisoners of war from the sawmill at Mankendorf. They’re improving the road for the timber lorries, but I could spare a man or two to help you at the busiest times. My orders are to improve forestry and agriculture in the region. It’s a big farm for the two of you.’

‘Three,’ said my brother, and my mother put a warning hand on his shoulder.

The captain nodded seriously. ‘Three.’

He was right, of course. Even if we worked from sun‑up till sun-down there was no way my mother and I could do the work of my father, my brother Jan and the two hired men we’d lost.

‘What’s your name?’ the captain asked my brother in a friendly way.

He hesitated and then said, ‘Marek’, the name he had from his Czech grandfather. Outside the house and at school he normally used his other name of Heinrich, from our mother’s father. My mother and I glanced at each other, but didn’t speak.

‘It’s a very nice farm,’ the captain continued. ‘I grew up on a farm, and I know how much work it can be.’

I was thinking that I preferred the real Nazis, who didn’t bother to make conversation, but searched in every room and turned over the contents of every cupboard without asking, as if it was their right. You could hate them with white-hot venom. We kept our eyes fixed on the floor when they were in the house, knowing that our faces would betray our loathing.

But with the Oily Captain, even the first time, when I stared at him, he was the first to look away.

‘What’s most urgent?’ he asked.

‘First, the hay must be cut before we have a thunderstorm,’ my mother said, and he nodded. It was odd to hear her speaking German in the house. We’d only spoken Czech here for five years, ever since the Nazis marched into Prague.

‘Tomorrow morning then,’ he said, and replaced his hat and raised his arm in a salute, which looked more as if he was trying to keep the sun out of his eyes. ‘Heil Hitler.’

We muttered unintelligibly, and he turned and left. Marek sat down again.

The captain’s footsteps clicked away from the house. He held one leg stiffly, and you could hear it in the irregular clack of his boots. I supposed that was why he wasn’t away slaughtering Russians or hunting down partisans like my father and Jan. Perhaps he had a false leg.

When he was out of earshot, my mother exhaled and reverted to Czech. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘I can’t say it won’t help. As long as he isn’t around poking his nose in all the time.’

The Prisoner's Wife Maggie Brookes

A debut novel set in 1944 war-torn Czechoslovakia amid the extreme privations of a prisoner of war camp. Based on a true story, passion, heroism and a love that transcends overwhelming odds.

Buy now