- Published: 8 January 2019

- ISBN: 9780857988546

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $34.99

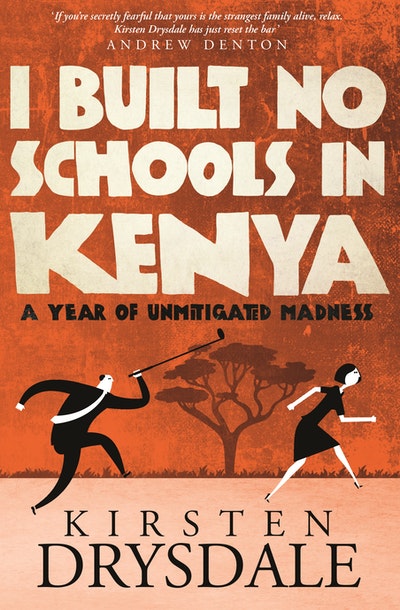

I Built No Schools in Kenya

A Year of Unmitigated Madness

Extract

Millicent is an old family friend of the Smyths, a fellow former colonial, a couple of decades Walt’s junior. She blends in a bit better than Alice and me. We’re in our mid-twenties and come from Mackay, a town in regional Queensland. We’ve had to learn the ways of this world.

The Kenyan household staff are just getting on with things as best they can. There’s Esther, the maid, James, the gardener, Khamisi, the cook, Peter, the driver and Patrick, the security guard. There’s also David, who looks after the granny flat out the back, and Frank, the night shift guard – but we don’t see as much of them. Most of them have been working for the Smyths for a very long time – though I don’t think it’s ever been quite the punish it is now that Walt’s sick and surrounded by a team of meddling mzungus. Not that they ever complain.

Walt’s house is in one of Nairobi’s nicer suburbs. It’s one of the area’s older, more modest homes, surrounded by hedge-hemmed mansions boasting tennis courts and swimming pools. Someone very important has a place just down the road – in the evenings you can hear their helicopter coming in to land. When I jog past their high gates I’m watched by camera lenses and rifle sights, and barking dogs that scare me over to the other side of the road.

As for Walt himself – well, he’s an anachronism. An old-school colonial from early establishment stock. His father was one of the first white men out here, one of those guys you imagine arriving with a sack of Union Jacks slung over his shoulder, marching along in a pith helmet from the coast to the Nile, laying claim to land with every few steps on behalf of the Empire and promising to ‘civilise’ the ‘natives’, as though there’s anything ‘civilised’ about subjugating people in their own country. On Walt’s mantelpiece is a photograph of Teddy Roosevelt when he came to Kenya on a hunting safari in 1909. Except it wasn’t called Kenya back then; it was still the ‘British East Africa Protectorate’, one of the many pink patches on the map.

So you see, these people are a big deal around here. At least, they used to be. Modern-day Kenya barely knows or cares that they exist. Old colonials are literally a dying breed.

Walt has so much money it will never run out. It’s partly inherited and partly self-made. He was a farmer, of tea and coffee and cattle. I’m told by the household staff that he worked hard to turn unproductive land around, and was nearly bankrupted doing so. Daniel arap Moi, Kenya’s second president, admired Walt’s farm so much he compulsorily acquired it from him in the 1980s. Walt was lucky to receive a good price. Independent Kenya, for the most part, made a point of being relatively gentle with its former colonial masters. Whether that was for better or worse depends on who you speak to.

Anyhow. Now Walter Smyth’s in his eighties, and his mind is falling apart. He’s got vascular dementia: a demolition team of tiny strokes and little wrecking balls of sticky protein are destroying his brain, leaving a rickety frame of consciousness behind. Walt grasps at the past and hallucinates much of the present. His body isn’t quite as shaky as his mind, but he does have a pacemaker and a dodgy liver and kidneys that need keeping an eye on. Most days, Walt thinks he’s in England, where he lived half his life. He thinks it’s 1942 and he’s collecting Second World War bomb shrapnel from the fields near his school. Or he thinks it’s 1985 and his mother has just died and he needs to get his suit ready for her funeral in Dover. Some days he does think he’s in Kenya – but that it’s 1956, in the middle of the Kenya Emergency, and he’s up on the tea farm, and needs to drive to the city for supplies, and might be attacked by Mau Mau terrorists on the road to Nairobi, and so needs to find his guns. He never thinks it’s 2010 and he’s already at his house in Nairobi, the one he’s had for thirty years. Even that lion hanging on the dining-room wall doesn’t jog his memory. You’d think it would – he’s got scars all the way down his legs from its claws. Those yellow teeth were sunk deep into Walt’s foot when he finally managed to unjam his rifle and send a bullet through the side of its skull. Now the lion watches him eat, its jaw frozen in a silent roar.

There’s no good reason for my being here (though there are plenty of bad ones). I have no nursing experience. All I know about dementia is what I saw as my grandmother’s mind crumbled to dust in the latter years of her life: the way she would conduct orchestras at the dinner table using chicken bones as batons, or cut pictures of puppies out of tissue boxes and glue them to the back of her couch because they were ‘sweet’.

More than anything else, this whole story is the result of cosmic timing.

In September 2010, I’d just started working in television, back home in Australia. But Hungry Beast – the show I worked on – had finished and we weren’t sure it would get another season. Having uprooted my life and moved to Sydney for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of working for Andrew Denton, I was in a weird place. In one sense, I felt I had the world at my feet. But I wasn’t at home in Sydney. I was lonely, a bit lost, and in hindsight probably mildly depressed.

Just as I’d decided to move back to my family’s farm in Mackay for a while, Alice called from Nairobi with a somewhat intriguing proposal. She’d been hired by the Smyths through a carers agency while she was living in London, and when they decided to return to their home in Nairobi, she agreed to go with them. But the job was too much for one person alone – they needed more help.

‘They just want someone white, female, slim and switched on,’ she said.

‘Those first three seem a bit … icky, dude.’

‘No, no, no – it’s not like that. The thing is, we’re living in the house with Walt. So even though he doesn’t know what’s going on, we need to look like people he might have had in his home throughout his life. That’s why they can’t hire black carers – he’d never stand for it. And he’s terrible with fat people. Would comment on their weight all the time. Like, repeatedly, ’cos he forgets what he’s just said. It’d be way too awkward. But with me, he just assumes I’m some friend of the family or whatever. You’d fit right in.’

‘He sounds like a total arsehole.’

‘Oh no, he’s really quite sweet! Well, most of the time. I mean, obviously he’s a bit racist. And sexist. But that’s to be expected. He’s a product of his time! And look, he can get a bit cranky and frustrated now and then, but it’s easy enough to calm him down by flirting with him and making him laugh.’

‘Mm,’ I said, slightly revolted. ‘And all we have to do is make sure he doesn’t run off and get lost?’

‘Yeah it’s cruisey as! You pretty much just have to help him get dressed in the morning, sit and read the papers with him on the patio, and make sure he takes his pills. He can go to the toilet on his own and all that – it’s just keeping him company, really. Giving him someone to talk to, ya know?’

‘So, does this guy know he’s got carers? I mean, how did he hire you in the first place?’

‘His daughter, Fiona, is organising everything for him. She’s the one who found me through the agency. Walt’s wife – that’s Marguerite – is still in England. She’ll come over to join us in a few weeks.’

‘Right … And how long are you planning to stay?’

‘Just a few months, then I’ll go on safari. Fiona wants me to help recruit other carers ’cos we really need to have someone on duty at all times and she’s really keen on Aussies. Reckons we’ve got the “thick skins and nous” for the job.’

I can see how someone might draw that conclusion from Alice. She is one of the most robust people I know: a Muay Thai kickboxer with no time for nonsense and niceties, while remaining empathetic and perceptive. She’s like a kindly nurse with a six-pack. But I did think it seemed odd to apply that singular character assessment to an entire nationality. And to bring someone to the other side of the world without vetting them first.

‘Doesn’t Fiona want to interview me or anything?’ I asked.

‘Nah, she trusts my judgement! So you’ll do it? They’ll fly you over and everything. It’s a decent daily rate and you won’t have any living expenses – all meals are provided, unless you want to go out of course. And you’ll be able to go travelling around a bit too, in time off.’

Well. There were a few hurdles for my conscience to clear. Taking a job I’d been offered explicitly because of my skin colour? That job being to care for a man whose riches were partly colonial spoils?

I pondered, then I did what white people are so good at doing: I pushed all those niggling issues into the corner of my mind. I told myself it was hard to refuse a proposition this odd. But a few additional factors pushed me to accept it. Maybe, I told myself, I could get a bit of journalism work over there. Pitch some articles, bone up on my writing. Yes! It would actually be a career move. I also happened to have good friends – a couple – working for the Department of Foreign Affairs, who had just been posted to the Australian High Commission in Nairobi. Knowing I’d be able to tag along with them in my free time made the prospect of developing a social life and making good contacts in the country much more likely.

The third factor – the main thing, really, feeding my curiosity – was my own connection to Africa. My parents and most of their immediate families left Zimbabwe for Australia in the early eighties, but all our history – for several generations, on both sides of the family – is back there, somewhere, scattered across the continent along with a few remaining distant relatives.

I’ve always been fascinated and appalled by my family’s stories of life in Africa. That exciting and romantic but fundamentally unjust colonial life was so many miles and years from my upbringing in sleepy little Mackay – and my progressive millennial persuasion – that it seemed as though it couldn’t possibly be real, couldn’t have ever been real. Still, I had an overwhelming longing to see it. The Finnish have a word for this strange emotion: kaukokaipuu. A feeling of homesickness for a place you’ve never been.

So. Although Kenya is a different country, thousands of kilometres from Zimbabwe, it is still Africa, and the time-warp colonial world of the Smyth household would be something akin to the one my parents had known. This was a pretty rare chance to see it up close. Probably as close as I would ever get.

I told Alice to book my flights, and I landed in Nairobi a week later.

The thing is, when my good friend Alice called to offer me a job on the other side of the world, she didn’t give me the full story.

Not even close.

Big chunks were missing. Huge chunks. Crucial chunks, you might say. Chunks you can be sure a person would want to know about before signing up to a gig like this.

So when I first arrived at the Smyths’ house in Nairobi, I was more than a little baffled when the first thing Fiona – who was visiting at the time – said to me wasn’t ‘Hello!’, or ‘How was your flight?’, or ‘You must be tired! What a long way you’ve come.’ Nope. Nothing like that.

The very first thing Fiona said to me, in a low voice while looking at me sideways, was simply: ‘You’re brave.’

I Built No Schools in Kenya Kirsten Drysdale

This is not your standard white-girl-in-Africa tale. I fed no babies, I built no schools, I saved no rhinos. Self-discovery came a distant second to self-preservation on this particular adventure.

Buy now