- Published: 3 May 2022

- ISBN: 9781761044007

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $34.99

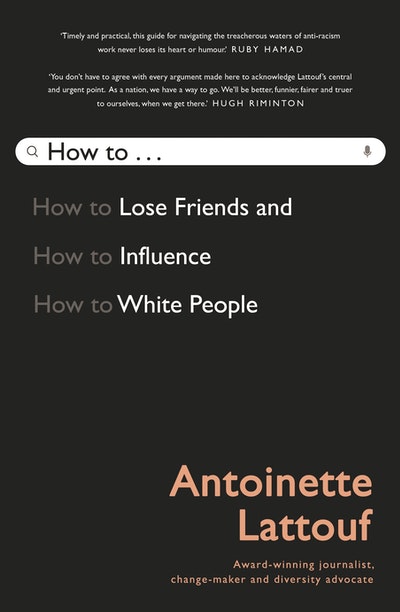

How to Lose Friends and Influence White People

Extract

The #MeToo movement, and more recently, the Black Lives Matter movement are rattling the dominance of the white middle class. Global awakenings like this are rare.

Black Lives Matter began as a hashtag (#BlackLivesMatter) after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager, who Zimmerman killed in February 2012. Its momentum skyrocketed following the slow-motion execution of George Floyd at the hands of a white police officer in Minneapolis in May 2020. The horrifying brutality was caught on camera, and people all over the world saw for themselves a man die while begging for the right to breathe. Tragically, his calls, and those of helpless bystanders, were ignored.

For the people who have been most acutely affected by the attitudes, policies and behaviours of the white status quo, these movements have allowed them to express generations’ worth of repressed anger. Black Lives Matter also symbolises hope and a shift in power.

According to polls from a number of data science firms, Black Lives Matter may well be the biggest movement in American history. Within two months of Floyd’s murder, an estimated 26 million Americans protested and street demonstrations continued for weeks after that. There were mass rallies in at least 1700 locations, across fifty states.

Floyd was not the first Black man whose death in police custody had sparked protests. But this time it was different. The response was more sustained and widespread. As horrific as Floyd’s death was, the response was about even more than one man’s death. And while the movement started in North America, its message resonated far beyond those borders. At the heart of what Black Lives Matter seeks to eradicate is the decreased life chances for non-white people in many postcolonial Western countries, including Australia. It’s saying, ‘We have had enough’ to a system that is made up of all sorts of inequalities and injustices. And, moreover, that both implicit bias and outright racism are embedded not just in policing, but in all three pillars of democracy – the legislature, executive and judiciary.

Of course, there were people who came in to preserve the status quo. In Australia, political leaders and commentators in staunch defence of it routinely remind us that we are a thriving multicultural nation that has come a long way. This is usually substantiated with convincing evidence such as ‘I just love butter chicken and garlic naan. Our country is so much better off thanks to the quality of restaurants we now have.’ Or: ‘We had Chinese neighbours growing up who were so nice and worked so hard at the local dry cleaners to pay for their son to go to private school.’

And then there are these beauties: ‘I was chatting to my Uber driver, who is from Bangladesh or Pakistan, and anyway, he was telling me about his government and, boy, does it sound dicey there. I told him he’s lucky he got in. I know those drivers don’t make great money, but hey, it’s better than living in a slum.’ Or a discussion I overheard out the front of my daughter’s school: ‘I know old people and doctors should get the COVID-19 vaccine first, but why Aboriginals? I mean, they get everything given to them. I’m not racist, I don’t even really see colour, but we always have to pander to them, don’t we?’

In fact, not only are things so good now – these folks would argue – they are actually better and easier for non-white people. At this point, the discussion usually heads in the direction of the social welfare benefits and specific jobs created for Indigenous people, scholarships for refugees and mentorship programs for young Muslims, to name but a few ‘special treatment’ examples used to apparently prove that multiculturalism has swung so far the other way that it manifests in forms of ‘reverse discrimination’.

Enter the ‘All Lives Matter’ retort. When Black Lives Matter really took off, some people interpreted it as both divisive and confrontational. Rather than exclude non-Black people, some suggested ‘All Lives Matter’ was a nice alternative, and an innocent way of celebrating the worth of all humanity. Cue group hug. But there is nothing innocent and inclusive about denying the racially specific and longstanding struggles faced by Black communities by saying ‘All lives matter’. This phrase reinforces prejudice and is just a racist dog whistle. It’s like standing on your front lawn and saying ‘All pedestrians matter’ when your neighbour’s kid is on the road, badly injured after being hit by a car. It’s not the time or place to be talking about ‘all pedestrians’. It’s time to deal with what’s directly in front of you.

When I talk about ‘whiteness’, I’m not just referring to those who burn easily if they forget to put on a rashie at Bondi Beach, but rather the ideology that history set Anglo-Celtic and European (now more broadly ‘Western’) culture as the benchmark for righteousness and excellence. At times, I am reluctant to use buzz words like ‘white privilege’ because it’s often seen as a provocation that elicits defensiveness or an accusation of being ‘woke’. By the time you’ve finished uttering or even typing these two words, the people who could benefit most from listening have switched off. So, in the spirit of keeping unlikely bedfellows who are triggered by buzzwords engaged, I’ll describe the phenomenon as a ‘lucky ledge’. This ledge is very real, usually unseen, and comes with unconscious advantages beyond just cosmetics and convenience. It’s so comfortable and gives you the best view – it’s no wonder few are prepared to share it. Some don’t even realise they are on it! For those perched on it, life is pretty damn good up there.

This idea gained popularity in social discourse in 1988 when American academic and feminist Peggy McIntosh published a fifty-point essay called ‘Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack’. As a prologue to the fifty examples, McIntosh wrote: ‘I was taught to see racism only in individual acts of meanness, not in invisible systems conferring dominance on my group.’ She then explored examples of hidden benefits that white people enjoy and experience in everyday life.

McIntosh uses a knapsack (a precursor to the modern-day backpack) as a metaphor and ‘unpacks’ fifty scenarios that demonstrate the systems that allow racism to flourish. These are just a few that really resonated with me:

I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.

I can do well in a challenging situation without being called a credit to my race.

I can take a job with an affirmative action employer without having co-workers on the job suspect that I got it because of race.

And while her work echoes some concepts reflected on by Black rights activist and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois in the 1930s, it is ironic that it took McIntosh’s voice – a white woman’s – for these concepts to gain real currency.

Du Bois argued that privilege was more than just having money. It was a state of being that he explored through the idea of a ‘psychological wage’. Even white people who were poor had many advantages over Black people in the same dire financial position. For example, at the time, being poor didn’t stop a white person from being allowed to enter parks and schools and having the right to vote.

Similarly, in Australia, if you’re poor, have limited education and are white, you are still far more likely to have a better quality of life compared to an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person. On average, Indigenous males live 71.6 years (8.6 years less than their non-Indigenous peers) while women live 75.6 years (7.8 years less).

While it is well-documented that if you are white and male you are the most privileged, some white women aren’t doing too badly either. Migrant and refugee women are over-represented in casual, part-time and precarious service industry jobs. A 2018 report by the Australian Institute of Family Studies found women from migrant and refugee backgrounds experiencing domestic violence struggle more to get help because of language barriers, social isolation and insecure visa status.

It’s been more than ninety years since this ‘wage’ turned ‘knapsack’ and now ‘ledge’ was exposed, yet many white people still refuse to believe that privilege augments their lives. They cannot accept that the system is flawed, given the system favours them.

While some white people saw themselves as victims of Black Lives Matter, others couldn’t see how the movement was relevant to Australians. While observing the United States’ racial reckoning, one journalist’s reaction served as a microcosm of this belief in Australia’s apparent racial harmony.

During a live cross with a commercial breakfast television program, the Australian reporter, based in Los Angeles, asked what a Black protester meant when he said ‘The country was built on violence’. The protester gave her a long and passionate response. The reporter wrapped up the interview by thanking the man for his insights.

‘I really appreciate you giving your perspective, mate, because people in Australia don’t have the understanding of the history of police killings and things here,’ she told the man, from behind a police blockade.

This led to a social media outpouring of disbelief over the journalist’s ‘embarrassing’ and ‘shameful’ comments due to her inability to draw any parallels to the police treatment of Indigenous people. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander activists, artists and academics including rapper Briggs and writer Nakkiah Lui described the coverage as ignorant, pointing to evidence and data that demonstrates the enduring incidence of Black deaths in custody in Australia.

There was plenty of constructive criticism about how damaging the reporter’s ignorant comments were, but unfortunately, social media was true to its harassing form, and there were also quite a few nasty and offensive comments hurled the reporter’s way. However, rather than taking a moment to digest why people were outraged, criticism of the young, blonde, female reporter was quickly met with defensiveness by many fellow white journalists. During my interactions with journalists at the time, one thing really stood out. They were more concerned with pitying her and discussing the ‘unfair pile-on’ than exploring why it could have been a problematic cultural knowledge gap in our media and why it was problematic that she overlooked generations of Indigenous trauma at the hands of police. Rather than focusing on feeling wounded or being defensive, why not take the incident as a moment to reflect and get educated?

While Black experiences of racism and systemic oppression in the United States are different from those endured by Indigenous people in Australia, there are overlaps, and it’s difficult to ignore what Black Lives Matter re-energised locally.

Suppose indeed this reporter believed that ‘people in Australia don’t have the understanding of the history of police killings and things here’. In that case, this belief could have served as an excellent example of how our unrepresentative news media can both inadvertently – and deliberately – affect our perceptions of racial divides in Australia, and indeed our understanding of and acceptance of our own history.

This is not to suggest Australia simply mirrors the United States.9 Our history and our power structures differ, not to mention our gun laws, population makeup and migration policies. But we are both Western democracies, colonised by the British, with Indigenous people slaughtered in the frontier wars. Our countries also have a close economic and political relationship. So, there are countless overlaps and indisputable Black Lives Matter flow-on effects.

And while modern history has never seen a racial reckoning on this scale, I did not see a single non-white – let alone Black – person from Australia’s media report on Black Lives Matter from the United States for a mainstream media outlet.

Here’s a wild idea for you. Buckle up, to ensure the audacity doesn’t knock you off your feet. Imagine if an Australian television network or other major media outlet had sent a reporter with an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander background to the United States to cover Black Lives Matter or the 2020 United States election. Bringing lived experiences, empathy and humanity to coverage, as well as greater cultural understanding, will help forge more genuine connections with diverse audiences. An experienced Black or Indigenous journalist – just like an experienced white journalist – can straddle fairness and balance. But an Indigenous journalist can bring something even more powerful and unique to the microphone, and that’s a greater ability to draw parallels and distinctions to Australia’s experiences with Black deaths in custody. They have skin in the game – in all senses of the phrase.

In 2020, Mary Lynn Young, a professor at the University of British Columbia, wrote a book called Reckoning: Journalism’s limits and possibilities. In an interview, she commented that the national conversation, driven by an overwhelmingly white United States media, has gaping holes in it due to the absence of many perspectives. Indigenous and Black voices are either limited or missing entirely. ‘What’s happened to the people who have actually been underserved, misrepresented, mis-served?’ she said. ‘Where did that conversation go and who’s been controlling that conversation in what we consider modern journalism?’

I’m not suggesting that only Black journalists cover ‘Black stories’ or only white journalists cover ‘white stories’. But having a diverse editorial team makes for better journalism, because it brings more balance, improves social and cultural awareness, canvasses different perspectives and enables staff to learn from one another. ‘[W]hen underserved populations don’t see people who look like them reporting the news, they are more likely to discount those news outlets,’ American journalist Dale Willman wrote in an essay examining why journalism needs more diverse voices, a need highlighted at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement.

In Australia, federal government statistics estimate that one in four Indigenous people in urban areas and more than half in remote regions live below the poverty line. In NSW in 2020, Indigenous people were imprisoned at ten times the rate of the general population, despite only making up about 3 per cent of the state’s population. In rural and remote areas, the rates of incarceration are much higher. (Migrant and refugee groups can’t be quantified, as this data is not captured by the justice system.) Health, literacy and employment figures are equally alarming. Given how widespread these issues and barriers are, there’s a good chance an Indigenous journalist will have a better understanding of issues around poverty, poor health outcomes or the criminal justice system – the very issues being canvassed in the Black Lives Matter movement.

Not to mention that in tense and charged environments, people of colour can sometimes feel more comfortable when approached by a person who looks like them and shares a culture and a language – even if it’s just local slang. As an Arab woman, I’ve lost count of the number of times I have been able to get interviews over the line when covering stories in Western Sydney, because I grew up there. I understand the geography and the people. Being able to speak Arabic has helped enormously too. In situations where I’ve seen white reporters ignored or turned away, the same interviewees have shown ease and comfort towards me because I’m a more familiar face. It really isn’t rocket science, it’s just social science.

This was also explored in an article discussing a 2016 United States study on how journalists cover race-related stories. The study found that ‘many of the [white] reporters had trouble getting Black sources on the record and turned to personal connections, fell back on existing contacts with Black leaders, or turned to Black sources who had contacted their newsrooms’.

The white journalist who thought Australia wouldn’t understand the United States’ ‘history of police killings and things’ demonstrated her position on the ledge in her interview with the Black Lives Matter protester. Her reality was elevated so far up from the most disadvantaged Australians – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – that she could no longer see them. So while she was reporting on years of trauma and angst over racialised policing at the Black Lives Matter rally in an American context, her omission, or even dismissal, of Australia’s shameful treatment of Indigenous people was not surprising.

How to Lose Friends and Influence White People Antoinette Lattouf

A guide through the balancing act of activist, advocate and ally, remembering that just because others are learning you don't need to be the teacher, from the dynamic and sharp co-founder of Media Diversity Australia, Antoinette Lattouf.

Buy now