- Published: 1 December 2020

- ISBN: 9781760899196

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $24.99

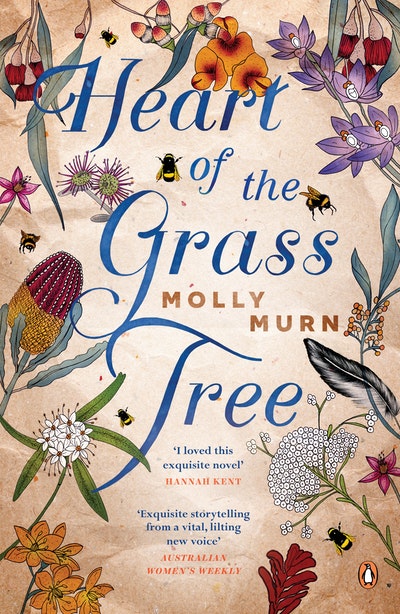

Heart of the Grass Tree

Extract

Because of the island’s isolation from the mainland, it is its own protected entity, and here the Ligurian bees have found a sanctuary in which to build their pristine citadels. My mother used to say that the honey of her bees was the island transmuted, that in its viscous gold you could taste hints of salty coastal heath and white mallee and sugar gum and ti-tree and the very tang of the sharp midnight air, or the midday sun, robust and concentrated. And I liked to think, because of the Italian heritage, a hint of something alpine, windswept, exotic.

Once upon a time I was in love. I was only fifteen, so what did I know of love, except that when it rained it was the fecund smell of our love-making, and when the sun shone it was his warm hand on my breast. And I thought it a private, secret thing, our love. Schoolgirls were not to know what men and women really did together. But I knew. I knew, and I didn’t want it taken away from me. I also knew what the terrible consequences would be if we were to be discovered. Not just for me, but for him, too. In his family, there were complex laws that governed who belonged to whom, which were far beyond my naïve understanding. Yet we were beautiful together; we fitted. I remember our fingers entwined—mine luminous pale, his velvet dark—a perfect chiaroscuro.

I was only a girl. I didn’t realise then that when two people make love together, impassioned concentrated love, there is a contract made. Call it a spiritual vow. What I mean to say is that one can only truly give of themselves to another if they are willing to bear the fruit of that union. And I don’t just mean in the biological sense (although I learnt about that only too well); I mean that something is made by and between lovers so precious that they are rendered vulnerable, completely vulnerable, to that precious thing breaking. I knew nothing of this when I loved Sol. I was just being carried on the wings of something much larger than myself. Loving Sol felt right. Now that my body is softer—like worn velvet—more slow, less mine, more mine, I look back and know that we were only learning. We were novices—at sex, at love, at being ourselves—

but we were gentle and kind and reverent with each other. And we laughed. We were innocent to the consequences of our being together, of being drawn to each other’s honey.

Mother started beekeeping when Father got ill—a bout of influenza that left him so depleted it was months before he could get through a day’s work without shaking, without stopping to sit down every half hour—so Sol and I must’ve been about thirteen years old. For a good while, Mother’s honey was in high demand, and it helped tide things over while Father was recovering. Her Hog Bay Honey was not sold in the Hog Bay Store; our neighbours would come to the house directly to buy honey. Soon enough, Mother was also selling honey biscuits, honey cake and honey apple tarts from the kitchen door, just about as soon as they came out of the oven. She became known simply as ‘the honey lady’.

In my memory of the honey harvest of late summer, Sol is always there. He’d wander over from his family’s farm, which neighboured ours, but was a good hour’s walk away, in his bare feet, and with his skinny yellow dog, Gem-Gem, in tow. I remember Sol as a streak of blue. I don’t know why. Perhaps because his shirt was always blue. Or perhaps I have gazed out at this ocean for so many years that somehow the glinting blue out there and Sol, dear Sol, have become one and the same. He is always moving, always mercurial, always on the edge of things, and blue blue blue.

It is the later beekeeping years that I remember most clearly. I would find Sol waiting on the back doorstep in the shade of morning, drawing in the dirt with a piece of fencing wire which had a small loop at one end and was bent into a curve so that when he wasn’t using it, he could hang it around his neck for safekeeping. I would bring him a steaming cup of tea, which he gulped down in three big slurps before springing to his feet, and saying something like, Thank ya, gorgeous, while winking at me in my long sleeves and baggy trousers, and then smoothing over his inscriptions on the ground with his heel. Sol never wore anything but his regular clothes when bee-handling, his frayed straw hat pulled down so low as to almost cover his eyes. And I only saw him get stung once. It was right on the chest, under his shirt, and I remember that all morning

before the sting, Sol had been in a particularly bad mood. The bees were cross that day, too—butting against us angrily, their drone a higher pitch than I was used to, and Sol frowning and cursing. I wish I could remember more clearly what he told me later that afternoon, but all I can recall is holding a cool flannel against his left chest, and his agitation, and his eyes of a darker colour than I was used to. But that was a harvesting day out of the ordinary.

Mother thought Sol made the bees calm, which is why he became known as Smoky in our house. She thought he didn’t need to use the smoking canister to subdue the bees, but of course he did need it. I’m not that crazy, he would say. He was fearless, and the bees knew it, but he was also sensible. I never called him Smoky; to me he was always Sol. Sol of the bees. Sol of my heart. And of course, he has another name too. It is time to write of him. Time to write of us. But how? I’m afraid. I’m afraid of words. And what unloosing them will bring. Once written, they are so set down, so finite. I’d sooner paint. I know how to speak in pictures. When I paint it is heart to brush to canvas. Nothing in between. Beyond thought; beyond feeling. Beyond words. But now, I’m afraid. I’m afraid that if I don’t utter these words they will be lost. And I want them released. I want them found.

The house is swept, dusted, mopped, scrubbed. I’ve started another sculpture. A thing of bones. I’ve walked and swum and scraped a new supply of salt from the rocks for the pantry. I’ve been in to Kingscote for groceries, and I’ve phoned my granddaughter, Pearl. I heard something in her voice—a catch, a holding back. We must talk again soon. She thinks my cough sounds serious. From paint fumes and smoking, she says. She worries too much. I’ve been to the doctor about my chest, but she just says that I need to rest. Stress. It’s more than that, though. If I don’t set these words down, this tightness around my heart will only get worse. The stuck words will stop me from breathing. Please help me. Today the sea is glassy flat. A blank page. So bright it throws the sun right back at your eyes.

I take down Sol’s story-wire from its place on the ledge above the window. I haven’t touched it in years. The wire is thick, heavy, slightly rusted. I place it in the centre of the kitchen table (my mother’s oak table) that has seen so much. I walk tentatively to my bedroom. Slow, like I’m performing a Japanese tea ceremony. I find the pale-green shoebox, stashed away at the back of the wardrobe, and carry it carefully back to my writing place. I am uncertain. When I paint, I fly. When I write, I might break.

A white-bellied sea eagle skims the water, dipping into a mirror. I think of my daughter, Diana. I don’t want to be angry with her anymore. She is too much like me. A mirror. And Pearl’s turned out fine. More than fine. Stronger than all of us. I arrange the contents of the box in a semicircle around my notepad, with Sol’s wire at the centre. The periwinkle necklaces spread out on one side, and the black glass scraper and woollen caps on the other. The smell of the patchouli leaves I’ve scattered through the box is pungent, grounding, overpowering. And I have a jar of Ligurian honey beside me. The island transmuted. I will eat spoonfuls as I write. I take up my pen—fine-tipped, felt—and I smooth my hand along the page. I begin with trepidation because I am afraid of what it is I have to say. Until this very moment, the words were taken from me,

fossilised, so that now as I turn them in my palm or line them up beneath the glass (my own exhibition), I am forced to see again, but worse, to feel again that long-ago moment frozen in time. I carry this fossil of memory.

Heart of the Grass Tree Molly Murn

Shortlisted for the Indies and MUD literary fiction prizes. Heart of the Grass Tree is an exquisite, searing and hope-filled debut about mothers, daughters, family stories, about country and its living history.

Buy now