- Published: 16 July 2020

- ISBN: 9781473562806

- Imprint: Cornerstone Digital

- Format: EBook

- Pages: 288

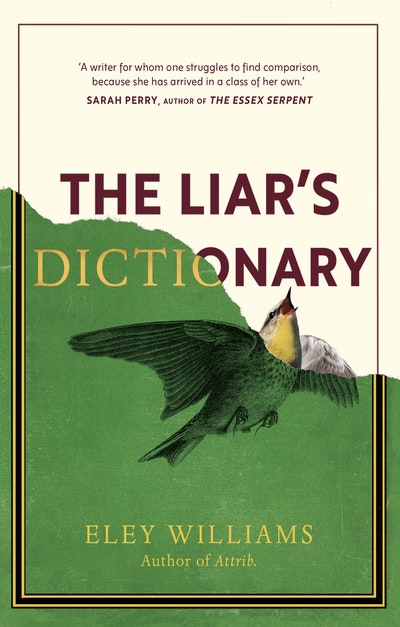

The Liar's Dictionary

A winner of the 2021 Betty Trask Awards

Extract

I admit that I have a less-than-great attention span so my perfect personal dictionary would be concise and only contain words that either I don’t yet know or ones that I frequently forget. My concise, infinite-as-ignorance dictionary would be something of a paradox and possibly printed on a Möbius strip. My impossible perfect dictionary.

Let us dip into a preface and push it open with our thumbs as if we are splitting some kind of ripe fruit. (Opening a book is never anything like that though really, is it, and this simile is a bad one.) My perfect dictionary would open at a particular page because of the silk bookmark already lodged there.

Two thousand five hundred silkworms are required to produce a pound of raw silk.

What is the first word one reads at random on this page?

[I have been sidetracked. Some words have a talent for willo’-the-wispishly leading you from a path that you had set for yourself, deeper and deeper into the parentheses and footnotes, the beckoning SEE ALSO suggestions.]

Exactly how many dictionary covers could one make by peeling a single cow?

Who reads the prefaces to dictionaries, anyway?

fnuck-fnuck-fnuck

To consider a dictionary to be ‘perfect’ requires a reflection upon the aims of such a book. Book is a shorthand here.

The perfect dictionary should not be playful for its own sake, for fear of alienating the reader and undermining its usefulness.

That a perfect dictionary should be right is obvious. It should contain neither spelling nor printing errors, for example, and should not make groundless claims. It should not display any bias in its definitions except those made as the result of meticulous and rigorous research. But already this is far too theoretical – we can be more basic than that: it is crucial that the book covers open, at least, and that the ink is legible upon its pages. Whether a dictionary should register or fix the language is often toted as a qualifier. Register, as if words are like so many delinquent children herded together and counted in a room; fixed, as if only a certain number of children are allowed access to the room, and then the room is filled with cement.

The perfect preface should not require so many mixed metaphors.

The preface of a dictionary, often overlooked as one pushes one’s thumbs into the fruit filled with silkworms and slaughtered cows, sets out the aims of the dictionary and its scope. It is often overlooked because by the time a dictionary is in use its need is obvious.

A dictionary’s preface can act like an introduction to someone you have no interest in meeting. The preface is an introduction to the work, not the people. You do not need to know the gender of the lexicographers who worked away at it. Certainly not their appearance, their favourite sports team nor favoured newspaper, for example. On the day they defined crinkling (n.) as a dialect word for a small type of apple, the fact that their shoes were too tight should be of absolutely no matter to you. That they were hungover and had the beginnings of a cold when they defined this word will not matter, nor that unbeknownst to them an infected hair follicle under their chin caused by ungainly and too-hasty shaving is poised to cause severe medical repercussions for them two months down the line, at one point causing them to fear that they are going to lose their whole lower jaw. You do not need to know that they dreamed of giving it all up and going to live in a remote cottage on the Cornish coast. The only useful thing a preface can say about its lexicographers is that they are qualified to wax unlyrically about what a certain type of silly small apple is called, for example.

The perfect dictionary reader is perhaps a more interesting subject for a dictionary’s preface. One generally consults a dictionary, as opposed to resting it upon lecterned knees and reading it cover to cover. This is not always the case, and there are those who make it their business to read full, huge works of reference purely in order that they can say that the feat has been achieved. If one rummages through the bletted fruit of history or an encyclopaedic biographic dictionary of dictionary readers, one might discover such a person, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, and a short biography dedicated to the same. Upon becoming the [SEE ALSO:—] Shah of Persia in 1797, Fath-Ali Shah Qajar was gifted a third edition of one very famous encyclopaedia. After reading all of its eighteen volumes, the Shah extended his royal title to include ‘Most Formidable Lord and Master of the Encyclopædia Britannica’. What a preface! A small picture of the Shah accompanying an article about his life might be a steel-plate engraving and show him seated, wearing silk robes with fruit piled high next to him. There is a war-elephant in the background of the portrait. So much fruit, so many silkworms, so much implied offstage trumpeting.

If you put your eyes far too close to an engraving all is little dots and dashes, like a fingerprint unspooled.

Perhaps you have encountered someone who browses a dictionary not as a reader but as a grazing animal, and spends hours nose-deep in the grass and forbs of its pages, buried in its meadow while losing sight of the sun. I recommend it. Browsing is good for you. You can grow giddy with the words’ shapes and sounds, their corymbs, their umbels and their panicles. These readers are unearthers, thrilled with their gleaning. The high of surprise at discovering a new word’s delicacy or the strength of its roots is a pretty potent one. Let’s find some now. (Prefaces to dictionaries as faintly patronising in tone.) For example, maybe you know these ones already: psithurism means the rustling of leaves; part of a bee’s thigh is called a corbicula, from the Latin word for basket.

For some, of course, the thrill of browsing a dictionary comes from the fact that arcane or obscure words are discovered and can be brought back, cud-like, and used expressly to impress others in conversation. I admit that I shook out psithurism from the understory of the dictionary there to delight you, but the gesture might be seen as calculated. Get me and my big words; phwoar, hear me roar, obliquely, in the forest; let me tell you about the silent p that you doubtless missed, etc., etc., and that psithurism is likely to come via the Greek ψι′θυρος, whispering, slanderous. How fascinating! says this type of dictionary-reader. I am fascinating because I know the meaning of this word. When used like this, the dictionary becomes fodder for a reader, verbage-verdage. We all know one of these people, whose conversation is no more than expectorate word-dropping. This reader will disturb your nap in the café window just to comment upon the day’s anemotropism. He will admit to leucocholy just in order to use the word in his apology as you drop your napkin and reel back, pushing your chair away. He will pursue you through hedgerows just to alert you to the smeuse of your flight.

Of course, this dictionary reader also celebrates the beauty of a word, its lustre and power, but for him the value of its sillage is turned to silage.

He would use crinkling as a noun correctly, with a flourish. (Preface as over explanation, as metabombast.)

There is no perfect reader of a dictionary.

The perfect dictionary would know the difference between, say, a ‘prologue’ and a ‘preface’. Dictionary as: so, what happens?

Dictionary as about clarity but also honesty.

If one is wont to index these things, another category of reader, submits to the digressiveness of a dictionary, whereby an eyeline is cast from word to word in sweeping jags within from page to page. No regard for the formalities of left-to-right reading, theirs is a reading style that loops and chicanes across columns and pages, and reading is something led by curiosity, or snagged by serendipity.

Should a preface pose more questions than it answers? Should a preface just pose?

A dictionary as an unreliable narrator.

But haven’t we all had private moments of pleasure when reading a dictionary? Just dipping, come on in, the water’s lovely type of pleasure, submerging only if something takes hold of your toe and will not unbite. Private pleasures not to be displayed in public by café windows.

A sense of pleasure or satisfaction with a dictionary is possible. It might arise when finding confirmation of a word’s guessed spelling (i.e. i before e), or upon retrieving from it a word that had momentarily come loose from the tip of your tongue. The pleasure of reading rather than using a dictionary might come when amongst its pages you find a word that is new to you and neatly sums up a sensation, quality or experience that had hitherto gone nameless: a moment of solidarity and recognition – someone else must have had the same sensation as me – I am not alone! Pleasure may come with the sheer glee at the textures of an unfamiliar word, its new taste between your teeth. Glume. Forb. The anatomy of a word strimmed clean or porched in your teeth.

The Liar's Dictionary Eley Williams

The eagerly anticipated, playful, and profound debut novel from an utterly original, award-winning writer.

Buy now