- Published: 1 December 2020

- ISBN: 9781761040405

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 256

- RRP: $29.99

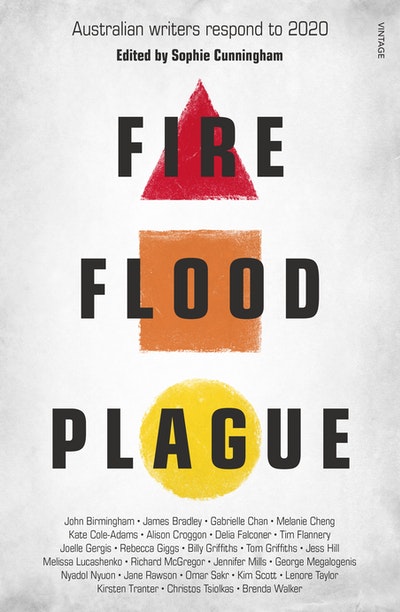

Fire Flood Plague

Australian writers respond to 2020

Extract

I’d wanted to do other things with my car this year. Specifically, I’d wanted to drive it to Bermagui on New South Wales’s South Coast, to spend time with family over the new year. But as the new year dawned – violent, smoky – there were bushfires to contend with, then air quality so dangerous my Canberran loved ones were trapped in their house. Soon enough there were hailstorms smashing into their workplaces. More fires, floods, then the plague. On it went. We understood that summer fires followed by late summer floods were considered to be part of the cascading effect of climate change. We understood that deforestation led to an increased likelihood of pandemics, but frankly, people can’t look every which way all at once and anyway it seemed that the genie was out of the bottle, the cat was out of the bag, the tipping point had tipped and now we were in the territory of the unprecedented, the territory of pivoting, the territory of grief and loss.

However, as a writer who has spent much of the last couple of years making gloomy pronouncements about the state of the world, there is one particular thing I didn’t see coming: the collapse of the federation and the dissolution of the State into its component states and territories. The impossibility of driving to Bermagui. I tried to get there once, twice, thrice, but first the Alpine Way was on fire, then the Princes Highway. For two months after that, various sections of road were closed between Victoria and New South Wales. At the end of March the roads were opened but Stage Three lockdown restrictions came into play. I planned to go in mid-July but by then, even if I’d been allowed to travel, the border had been closed.

I’m worried it might be years before I can spend time with my family again. Years before I get to see the forest of spotted gums lining the road that sweeps into Bermagui; or the sleepy town’s pelicans; or the pale-blue armies of soldier crabs pouring out onto the mudflats when the tide is low; or have the chance to walk the piece of old highway that has been turned into a nature reserve and left to fall into the sea. The Road, I liked to call it, in homage to Cormac McCarthy.

Many years are described as the year everything changed and perhaps that framing of 2020 is not ultimately useful. But it’s fair to say that the year 2020 will be remembered, at least by those who lived through it, as the year the human race fell off a cliff. It’s unclear how long that descent will take, how deadly it will be, and what shape we’ll be in when we land.

I am spectacularly privileged to have been spared – because of class, time of life, accidents of fate – from everything other than the existential crisis posed by the COVID-19 crisis at this point. My main experience is one of extreme claustrophobia. And if I had to pick the moment when I felt the most personal distress in a year which offered a cornucopia of anxieties I’d say that it was during the bushfires. I continue to reserve my greatest fears for what will happen when global temperatures rise 2, 3, 4 degrees. Which is all by way of saying I didn’t pay enough attention when I was sitting in a campground over New Year’s and a fellow camper read out the headline. ‘CHINESE AUTHORITIES TREAT DOZENS OF CASES OF PNEUMONIA OF UNKNOWN CAUSE,’ then commented, ‘Sounds like a worry.’ I was trying to find enough reception to track what was happening in Mallacoota, where 4000 people stood on the beach under blood-red skies as fires roared through East Gippsland.

The thing about change is that it makes no difference what we think we know, or don’t know; how many events we can take in at once, or respond to; how we might imagine we can keep safe. Jane Rawson speaks eloquently to this notion of safety. Is it achievable? Is it the point? And while we can entertain fantasies of self-sufficiency and national agency and whether we’re talking about carbon credits or COVID-19, we all breathe the same air, as Jennifer Mills points out, and we’re all ‘bit players in a complex ecology’. Borders and bluster meant nothing to the weather, or to the virus.

So, four months after I’d been camping, there I was, sitting in my car, working on this book, talking about what global economic collapse might look like. Wondering what would happen with China. Wondering how many lives would be lost in the United States before Trump (I refuse to use his honorifics) was managed (or thrown) out of office. Wondering how realistic a vaccine seemed. Not very, I thought, but at the same time I found it impossible to imagine quite what that looked like: a world where there was no vaccine. And to be honest, while I’ve often spoken and written about what environmental collapse might feel like, what I was quickly learning was that while much that has happened this year was predicted, the experience was continually surprising. Tom Griffiths describes the time between the fires and the pandemic as one during which, ‘people spoke courageously of “the new normal”, but did not yet understand that “normal” was gone . . . their masks were still in their pockets’ and soon enough they’d need them again. There is no returning to normal, and, as Alison Croggon writes, that can only be a good thing. Normal was not going well.

It is impossible to comprehensively document a year as profound as 2020 has been, but the writers herein have all charted different aspects of the terrain. Some essays are deeply personal, others have chosen to step back and offer us some perspective. Some of the difficulties and traumas that have erupted are too all-encompassing to be simultaneously lived through and documented, so there are some notable absences (homeschooling, working in a hospital, having a parent with COVID-19 in aged care, being shut into public housing with very little warning and no access to food or medical supplies).

I, like many of the writers in this collection, have found myself writing essays once, twice, thrice as we’ve progressed from bushfire and smoke-choked skies to the early days of the pandemic to where I sit now: working from my bedroom, in Stage Four lockdown, past the anxiety of the first stage and into the exhaustion of what is becoming a marathon. James Bradley writes bravely of the experience of his mother dying in the early days of the pandemic. Delia Falconer and her family fall through time as the year unfolds. Brenda Walker listens to a sonic version of the virus, Rebecca Giggs asks if our senses are changing, heightened, by the experience of plague. Kate Cole-Adams embraces new ways of relating as we’re kept at a distance from each other, reaching across borders and through time zones using technology. Kirsten Tranter mourns as she watches the ashes of our great forests rain down upon us.

The timeline we’ve included reminds us all how much has happened in the first nine months of a year in which a global pandemic has met environmental unravelling – confronted here by Joëlle Gergis – and fuelled an increasingly unhinged political scene. In this year of political chaos Lenore Taylor gives us some good news: fact-based reporting may be making a comeback, and if we follow the facts wherever they lead, the media will be strengthened at a time it is most needed.

Revisions have been required. Just before publication, Gergis reworked her devastating essay to reflect that the estimated number of Australian animals lost in the bushfire was not one billion but an unimaginable three. Omar Sakr finished a draft of his essay before the explosions tore through Beirut in August, then had to consider if words could do any justice to that horrendous event. George Megalogenis had to make a call on the potential impact of a cut in immigration, both as a result of COVID-19 and rising xenophobia in an increasingly unstable environment. He, like Richard McGregor, looked to the past to make his case, McGregor using history to help us understand what we might expect of our relationship with China in the months and years to come. Tim Flannery asks if there isn’t something to be learnt from our government’s response to the coronavirus. What can be achieved if we move from a place of denial to political will and action? Gabrielle Chan shows us the ways that rural communities are coming together to form new supply chains in a contribution that provides some welcome news, giving us a glimpse of the possibilities present in times of upheaval. Her exploration of economic models based on community suggests a return to a more collegial, hierarchical infrastructure, a possibility embraced in many of the essays. To do this, we need to push through what Kim Scott describes as neo-liberalism’s dog-eat-dog mentality to an understanding and an embracing of our Aboriginal heritage, an essential part of which is that we both listen to and adopt the Uluru Statement from the Heart. I write of the ways in which rural Australia is disenfranchised by the failing management of its lifeblood: water. This connection between our current economic and social structures and the problems we are facing recurs. Jess Hill traces the links between patriarchy, colonialism, the bushfires and the pandemic. Melissa Lucashenko reminds us that the idea of a safe Australia is an illusion the country’s First Nations have never enjoyed. The physical and economic constraints imposed by the pandemic on the population have been imposed on Indigenous Australians from the year 1788. White settlers brought pandemic with them and the colonial (and patriarchal) project unleashed both cultural and environmental damage we are all having to live with today. When Australians rallied in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, when they tried to make explicit the relationship between the murder of African-Americans at the hands of police and the appalling record of deaths in custody for Indigenous Australians, they were told that street marches were not safe. But being a person of colour is never safe in this nation and the responses to both the rallies and to those the media chooses to humiliate as the virus has spread is colour coded. These links between our past and present are delicately, movingly, described and explored by Billy Griffiths. John Birmingham vividly steps us through the othering of not just a people but of our entire nation, as fire engulfed our forests and the eastern seaboard. We were rendered to the rest of the world as TV news footage. Two dimensional. A nation in crisis. A nation to be pitied.

Christos Tsiolkas is bracing. He reminds us that those of us who imagined that our lives of travel and privilege, of relative ease, might last were dreaming. But, as I’m sure all who pick up this anthology will attest, few of us have slept well this year. As Melanie Cheng enunciates, the language of horror movies, the language of nightmares, is what is haunting us. Dreaming and hope don’t come easily. Nyadol Nyuon shares her hard-won knowledge: we need to resurrect our inner lives if we are to survive in this new world. Optimism sometimes seems impossible but finding hope and transforming it, constructively, into our lived reality is the only work worth doing right now. The question then becomes, what do we want to happen next? What is it that we are hoping for?

Fire Flood Plague Sophie Cunningham

Leading Australian writers respond to the challenges of 2020, to create a vital cultural record of these extraordinary times.

Buy now