- Published: 2 August 2022

- ISBN: 9780143791201

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $32.99

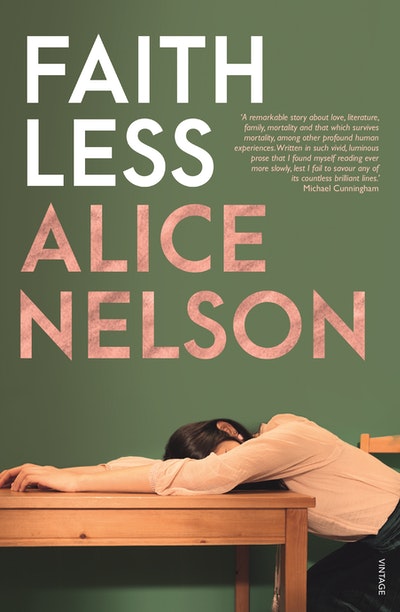

Faithless

Extract

Further up the shore Flora crouches by the water’s edge, her hands full of small stones. Her shoulder blades move under her dress like tiny wings. She is a child who has never seen the sea. If there is fear of it, or wonder, none of this is visible. Only a quiet watchfulness. Sometimes she cries out at night, high, warbling calls that startle her out of sleep. I keep the door between our bedrooms open so that I can listen out for her, but she never calls for me. If I go to her she gazes up as if from a great depth; as if she has been somewhere very far away and it costs her enormous effort to return. There is something unfocused and full of terror in her eyes in those moments and I think perhaps she does not recognise me when I come to sit beside her. She rarely cried when she was a baby. Perhaps she knew, even then, that crying would not get her anywhere.

The small waves creep further up the shoreline and Flora steps hastily back beyond the water’s reach. A lone seabird wheels and calls above her, but she doesn’t turn her face to look up. In the weak sunlight, her pale hair looks almost translucent. It’s so long now, reaching nearly all the way down her back, but I don’t dare to ask her if I can trim it. If I narrow my eyes, she is just a shadow. A small shimmering smear at the sea’s edge. Some ocean sprite. A changeling child. Which she is, in some ways.

Sometimes, Max, I imagine that I see you in her. Not in the sense of any physical inheritance, but a fleeting essence. Something wary and remote. Haunted, you might say. Though her ghosts are not yours.

You wrote once that you did not believe in time, but in spaces that interlocked according to a higher order of stereometry and between which the living and the dead could move back and forth at will. A kind of ghostly curtain, perhaps. It was those of us who were still alive who might appear the more unreal in the eyes of the dead, you said. Only rarely, in certain lights and atmospheric conditions, were mortals visible to those who had slipped to the other side. I look at Flora’s tiny silhouette by the sea’s edge, staring at the horizon in a vacant reverie. Just one step and it seems she might slip quietly beneath the water.

Can you see her from wherever you are now? Can you see me, sitting here on the hard stones of the shingle beach, my arms wrapped around my knees, my linen coat too light for the strange chill of the autumn afternoon? Forty-one this year, almost the same age you were when we first met. Too thin, a few strands of white in my hair, a little greyness creeping into the skin. ‘She remains in possession of her formidable beauty,’ an earnest journalist wrote rather obsequiously in a magazine profile last summer. As if beauty were something that might be carelessly misplaced and I should be commended for holding onto mine, however diminished. Still, a little thrill of satisfaction on reading that line, a little quiver of vanity. Formidable, though. It hardly seems the right word. My shaking hands, my pounding heart.

You gave me a stone from this beach, pale blue and perfectly oval. A parting gift, pressed into my hand like a coin or a key. We are so accustomed to leave-takings, you and I. So many departures and farewells, trains rolling out of station after station. India, London, Suffolk. I can never stand on a railway platform without a pang of remembered desolation, a sharp little stab of abandonment. Your hand on the glass of the window, your figure disappearing into the crowd, hurrying back into your real life. Sometimes it felt that I was always watching you walk away, Max. That even when I held you in my arms you were on the brink of departure, a part of you poised to go. I remember once thinking desperately, as I lay in bed watching you dress to leave, that if you were to die, if you were to no longer be in the world, then perhaps eventually it would be less painful than this. That then I could turn you into a memory, make you become the cleanly grieved past rather than a wound pressed on again and again. Something as simple as sorrow would surely be easier to withstand than this welter of pain and pathos and jealousy and yearning. But now you are gone and I cannot bear it. I cannot bear it. Since I have been in Dunwich, the reverse haunting you wrote of has come to seem entirely possible; our solid earthly lives rendered insubstantial and precarious. Because it is you, Max, dead these last three weeks, who seems the most potent of any of us.

So many times, over the years, in the minutes after you left me, I would imagine that you might return. A door banging or the sound of footsteps in the hall and I would be sure for a moment that, halfway down the stairs, or reaching the corner of the street, you had changed your mind and come back. That you had not been able to leave me.

How pitiful I make myself sound, how passive and lovelorn. A woman waiting. But still, my hopefulness would hang in the air, as potent as the scent of you on my pillow. It was a hopefulness that always had something sickening and desolate about it, because I knew it was false. Even as you sat on the edge of the bed to tie your shoes, you had already left me. Your mind was already on the journey ahead, the journey home. Home. Strange how that one small word, spoken by you, always held the power to turn me queasy with loss. It was a word that slammed a door in my face.

Long ago in Holland, in homes where there had been a death, it was customary for all paintings depicting landscapes or people or the fruits of the field to be covered. This was so that the soul, as it left the body, would not be distracted by a last glimpse of the world it was leaving forever and refuse to depart. The ambush of longing. The stubbornness of desire. Sometimes I think that we never stop wanting what we can’t have. Did you glance back, Max? Did you want to stay? Even for a moment, did you want to stay with me?

Faithless Alice Nelson

SHORTLISTED FOR THE AGE BOOK OF THE YEAR Faithless is a remarkable story about love, literature, family, mortality and that which survives mortality, among other profound human experiences. Michael Cunningham, Pulitzer Prizewinner for The Hours

Buy now