- Published: 31 August 2021

- ISBN: 9781760893224

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $32.99

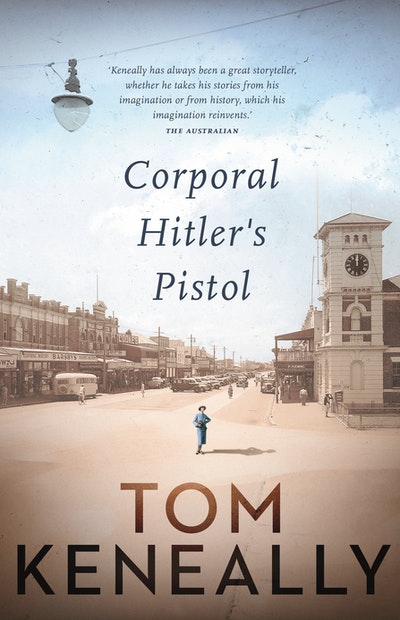

Corporal Hitler’s Pistol

Winner of the 2022 ARA Historical Novel Prize

Extract

1

Kempsey, New South Wales, 1933

On Friday afternoons Flo Honeywood, wife of the eminent master builder Burley Honeywood, was required to go forth, her body bathed, her face powdered and rouged, her figure, which was not that of an old lady, enhanced by a corset ordered from Sydney, a secret not shared with the women who sold such things in Barsby’s store in Smith Street. She wore, too, a best umber cloche hat bought at Anthony Hordern’s in Sydney, and she went out in her innocence as a woman ordained to meet and talk with the august of the river, the big people from the big acres from Toorooka northwards – the wife of Dr McVicar, the wife of the solicitor Sherry, the aged spouse of the other lawyer, Cattleford, the wife and eldest daughter of Collopy, the Shire president.

It was essential that Flo be on Smith and Belgrave streets pausing to speak, to discuss the Sydney schools to which they would send and had sent their children, the forthcoming tennis weekends at the homesteads up along the river, how their husbands were, and whether the frock salons along Belgrave Street had anything worth buying before each of them made their twice-yearly raid on Sydney.

Mrs Dunster had a daughter in Paris learning to be an artist! If she had a daughter on the moon it could not be more astonishing. Mrs Dunster must be heard from. There was much talking to do with that. Mrs Dunster admitted she did not understand what her daughter was learning – it was all described in letters, but in terms which evaded the limits of a town like this. ‘Half the time I don’t know what she’s telling me,’ Mrs Dunster very happily admitted.

But what a thing for a girl from here! A Macleay girl! Paris. Men had been sent, of course, to France in the Great War. But for someone to experience it with an artist’s eye – that was exceptional and, indeed, without precedent.

Kempsey had suited Flo – till she saw the boy. She had had a sense until then that it was her appointed place in the dispensations and empires of man.

The blot on Friday afternoons these days was the number of travelling men in old fragments of suits who had been able to pick up food ration tickets at the police station as long as the previous stamp in their ration books showed they had travelled more than fifty miles since the last week. They looked battered, dispirited, and carried a swag wrapped up in a blanket. But Friday was a day they could rest before moving on to the next town, to be replaced next week by another tribe of the poor who lacked jobs.

Flo had no malice against them, and in fact felt for them, but they were unsightly in their misery and detracted from the spirit of shopping day. Today, though, her progress possessed a torment that exceeded theirs, as she looked for, and feared seeing, the boy’s face.Did they know, she wondered. Had the townspeople even noticed the boy wearing Burley’s features? Did they know, from that boy’s face, seen in passing, what Burley had been up to? Some years back, but when he was already married to her! Was what Burley had been up to noteworthy to some, or condemned as sin, or barely spoken of, or long forgiven as a venial matter? Did some of the other women ever see half-caste boys whose faces came from their husbands? Or did they all have some easy power, as she had had till now, not to notice in the first place? She had noticed only last Friday. How many other Fridays had she seen the boy without knowing she had? But what if they had seen, as she had just seen now? Could their power to deny seeing their husband’s features undeniably in a kid from the blacks’ camp remain intact? If it could, what a gift that would be!

If you went on appointed rounds, though, as regular as the moon visiting the oceans, it made you feel as if you were fixed and permanent and necessary to the world. Well, now, after seeing the boy, she felt fixed to Belgrave Street by a thread, and she feared the thread would break very soon and commit her into a chaos of clouds. All solidity within the valley and the town was gone now. She felt she was a mere whisper. She dressed her bathed body well; she used the hatpin, better designed for a heart, perhaps her husband’s, than for a cloche hat, to tether hers in place.

After her encounter last week with what had to be her husband’s Aboriginal son, she had continued on up Belgrave, smiled and smiled to the point of aching, let her eyes glitter and glitter again, like a woman happy but, most importantly, safe from shame, and she knew herself that her laughter was strangely ardent and belonged to someone else. The wives of poorer people, the labourers, the carpenters, the timber-getters, slid by her with deference, and the sort of implicit envy she had until now enjoyed being the quiet object of.

After a conversation with some ladies on the corner of Belgrave and Verge streets, she progressed as far as the Commercial Hotel, at the back of which Mrs McIntyre kept reserved for the ladies of the town a lavatory, attached to the hotel by a covered way. There Flo went, after her perambulation of the town, and voided her bladder and then the contents of her stomach into the creosoted smell of the lavatory hole, and howled and swallowed again and again, and wiped her mouth.

The anguish of what had happened and a sense of the unexpected, vague demands it made on her had not gone away, nor been reduced to size by the passage of a week. She could not forget what had been seen. She could not fall back on any other men who looked like Burley and ascribe the kid to one of them. Time magnified the matter, in fact, the longer she stayed silent. She knew that she must now come out into the bitter and relentless light of the afternoon, to force herself back onto the street, and that she was ready to break her silence in ways Burley would certainly not like.

In Smith Street she ran into pretty Mrs Anna Webber – wife of Bert Webber, owner of a number of dairy farms and a hero of the Great War – and her daughter. They had to be spoken to for normality’s sake; it was not that she thought times normal, but they did. The Webbers were prosperous and owned dairy and cattle farms, as well as timber leases up and down the valley. The daughter had finished at the Presbyterian Ladies’ College in Sydney, and her complexion and eyes had a wonderful clarity, but today there seemed to be a few grave secrets clouding pretty Mrs Webber’s eyes, this child of German farmers, that were somehow and sadly comforting to Flo Honeywood to see, that made her feel less lonely – and all the more so since, as Flo and Mrs Webber and the clever daughter named Gertie walked up Smith Street, Anna Webber proposed tea at Tsiros’s Refreshment Rooms.

The effeminate and stylish Chicken Dalton, the straw-boater-ed pianist at the Victoria Cinema, passed by and bowed too theatrically to them. He might be as young as thirty-five or so, but she thought he had that look lilies get of going off, of crimpling and browning at the immaculate edges. The fact his cheeks were rouged – he did rouge his cheeks and, when he was performing, used lipstick – seemed designed to give him the look of someone suffering from TB, which he was not. Everyone knew he liked to see the new clothes from Sydney on the mannequins in the window of the dress salon owned by the Quinlan sisters, who had somewhat more fashionable clothing than that purveyed in Barsby’s department store.

Chicken was a town favourite in his way. Boys whistled at him and mocked him, but his answers were always so determinedly cheerful and unresenting, and he raised his boater in the manner of a vaudeville artist. Even Mrs Webber and Flo automatically smiled at each other as he passed, and Gertie sang, ‘Chicken Dalton!’ The town’s musician and licensed pansy – and you had to admit he could play the piano. On top of that, a number of men had testified that he had done great service in the war as a hospital orderly in Sydney.

To Flo, he seemed blithe. That might be why they called his type fairies, she surmised. Despite her dead feeling, she called, ‘We’ll be visiting you tomorrow evening, Mr Dalton.’

‘So are we,’ cried Anna, rejoicing in the minor coincidence.

Gertie addressed Flo: ‘My father, if you can believe it, Mrs Honeywood, is going to the pictures for the first time since he left the army. That’s fourteen years!’

Flo made the appropriate noises and found herself rewarded with the proximity of the great timber bridge over the Macleay, at the corner of Smith and Belgrave. She had got this far and not seen the boy.

She had, since she first noticed the boy, done nothing to break the routine of the household. She answered Burley functionally. Her elder son, Jerry, was holidaying on the south coast with a school friend’s family and was chary of spending too much time at home because Burley wanted him on one of the worksites about town, and currently that meant a new timber mill (and very welcome it was, said Burley, since there was not a lot else on the horizon) on the Crescent Head Road. Jerry had no ambition to learn the craft of hewing wood, and Burley did not have much time for a son who did not.

Jerry had been sullen with Flo and Burley during his time at home before Christmas, but had given Christian Webber, a young university student, driving lessons, and said he would do the same for Gertie if she ever got her head out of the film magazines. Flo’s two younger children went to school in Kempsey for now, and were minded by a girl named Bonnie, daughter of a large clan, happy for the work and very affable, and employed as an indulgence of Burley’s towards Flo.

So who was she as yet to say she would not parade the streets as his wife, and though a contrary intention was forming in her, there was no reason to resist the Saturday night routine of the pictures. Reserved seats at the Victoria. There, Chicken Dalton, wearing his tails, played the piano and musical contraption in the well beneath the stage.

Corporal Hitler’s Pistol Tom Keneally

<h3>Winner of the 2022 ARA Historical Novel Prize.</h3>

Buy now