- Published: 10 January 2023

- ISBN: 9781761046551

- Imprint: Hamish Hamilton

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $32.99

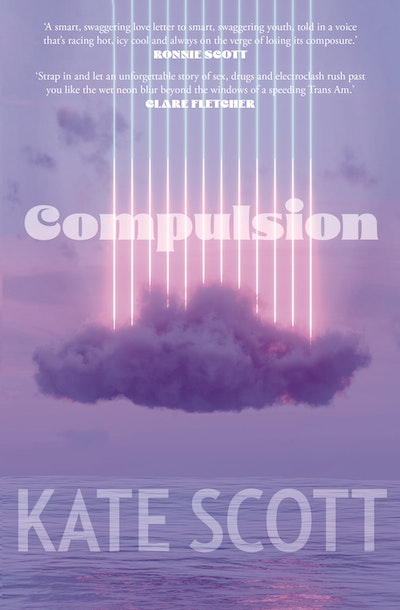

Compulsion

Extract

She slows and waits for him one day at the bridge, an unofficial marker between the national park and unclaimed craggy headland. She stands on her left leg, clasping her right foot behind her in a gesture of overstated awkwardness. Her nose is peeling. ‘Nice T-shirt,’ she says, gesturing at the faded Einstürzende Neubauten print. ‘I gather you’re not from around here.’

Robin laughs. ‘Nope. You?’

‘Ha! Actually, yes. I was born here,’ she points vaguely south. ‘I left Abergele at 14, but I’ve come back to take the cure.’

Chalk cliffs stripe the electric-blue sky. The ocean has a dry-ice shiver. It’s a coastline of staggering beauty on a clear, chiming day. ‘You’ve chosen a good place for it,’ he says.

She falls unselfconsciously into step with him as they walk along the bluff. Rangy limbs and dead-straight hair to her shoulders, lightest around her face. An odd, sideways-skipping step, an odd looseness at the joints. They map the points where their lives intersect: she went to school with Meg, who Robin is dating, for a few years in the mid-’90s. They’re the same age, save three weeks, and both studied English lit, but in different cities. They both love the new Ariel Pink record.

She tells him she’s burning through an advance to expand a long-form article into a book titled I Abject: Existentialism and Electronic Music. He tells her he’s staying with his sister to be near his grandmother in palliative care. It turns out they live on the same street, Lucy atop the hill, Robin a few blocks below. She has nicotine stains on her fingers.

They’re both sweating as they pause outside her house, sun claret with 4pm fury.

‘Care to come in for a glass of cold tomato juice?’ asks Lucy.

Robin, who knows just one person in this town outside the handful he’s related to by blood or marriage, says sure.

The house is split-level modernist. Her grandfather, her mother’s father, built it in the late ’50s. The front yard is a tangle of succulents, flushed with obscene flowers. There’s an outdoor spiral staircase leading to a rooftop terrace. Hammered urns hold jades and agaves, the front steps are gritty with salt.

Inside it’s much cooler, gnarled house plants swinging from cedar beams. The walls are the colour of mushroom bisque, the carpet the colour of peach sorbet, the kitchen the colour of avocado mousse.

Lucy builds their tomato drinks: tall glasses salted and peppered lavishly; the juice mixed to a froth with an oyster fork. ‘The best thing after a walk,’ she says. She motions for Robin to follow her back to the living room, a sunken nest of books and magazines. Copies of The Face and Select and Melody Maker and Record Mirror and ZigZag and Flexipop! and Ongaku Senka and Careless Talk Costs Lives are piled at the walls. A vast, misted window faces the sea. The coffee table is covered in crystal ashtrays, chewed pens, blister packs of painkillers, nail polish, more books, and apricot stones still bearing the fibrous tear of their fruit. Beneath the table is a scatter of ballet flats.

‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘I hadn’t realised how disgusting it’s become in here.’

The floor is slate, smoky grey and marmalade. There’s an old upright piano, a wingback chair of orange corduroy piled with dresses, and more plants: a bleeding heart that’s colonised one window, a Boston fern in a water-swollen basket, a fleshy purple thing in an oxidised copper pot.

‘You said this is your grandfather’s house, Lucy?’

‘Yes.’ Her legs are curled beneath her, glass pressed to her forehead.

‘His plants?’

‘His everything, except the records and magazines and clothes. And some books.’

‘When did he die?’

‘Oh, he’s not dead. He’s in India for a year, meditating. He found Buddhism in his 50s.’

‘As you do. How long have you been here?’

‘A month. But I grew up in this house if I grew up anywhere. We moved habitually with my dad’s job – every city on the east coast, the Mojave Desert, some other weird satellite towns: anywhere with an air force base, basically – so Abergele is the only fixed point in a chaotic universe. What about you?’

‘I’ve been here four months.’ Robin is self-conscious, having run out of things to ask or things that are polite to ask. He reaches for a Jenga-stack of books on the coffee table: powdery old editions of Either/Or and The Ambiguity of Being, a tea-ringed copy of Atomised.

‘Are you an existentialist?’

‘That’s an asshole thing to go around declaring. But if you define it as Sartre does, of creating oneself constantly through passionate action, then yes. Someone I call The Unspoiled Monster calls me a weaponised existentialist.’

‘What does that mean?’ He doesn’t ask who The Unspoiled Monster is.

‘That I use it as an excuse to behave badly, or used to. This year I’m channelling Camus: Happiness, too, is inevitable.’ She gives Robin a diffident look. ‘I’m sorry, I had a Dexie this morning to write, and I’m quite talkative. I don’t believe I’ve spoken to anyone else in days. Your sister – is she you doubled? Usually strapped beneath a baby?’

‘Um, yes. That’s Isabella.’

‘I’ve seen her around. Older, younger or the same?’

‘She’s older, five years older.’

They are quiet.

‘Well, I should let you get back to work,’ says Robin. ‘It was nice to meet you.’

Lucy stands, bounding towards the kitchen. ‘Wait there,’ she calls. When she returns, it’s with a crumpled piece of card. ‘I’m having a party this Saturday,’ she says, pushing an invitation into his hand. ‘You should come. Bring Meg. Bring Isabella. We’re starting at four.’

Compulsion Kate Scott

Set against the backdrop of the new millennium, a seductive summer read about obsession, sex, friendship and music from an exciting new talent. 'The cleverness is what's compulsive.' COURIER MAIL

Buy now