- Published: 15 September 2013

- ISBN: 9781590177068

- Imprint: NY Review Books

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $35.00

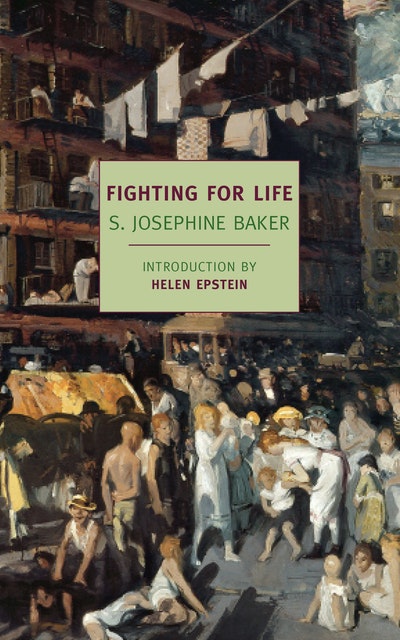

Fighting for Life

Buy from…

- Published: 15 September 2013

- ISBN: 9781590177068

- Imprint: NY Review Books

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 304

- RRP: $35.00

“Dr. Baker shines not only for her contributions to public health and social policy, but also for her work as a woman in government administration, supervising a staff that included many male physicians skeptical of women in medicine. She devised wardrobe strategies to minimize her femininity—man-tailored suits and shirts, stiff collars and ties—joking that her colleagues didn’t think of her as a woman and often disparaged women physicians in conversation with her. Her work made her a leading figure in public health and the New York City Bureau of Child Hygiene became a model for similar programs in other cities, as well as for the United States Children’s Bureau, established in 1912.” —U.S. National Library of Medicine