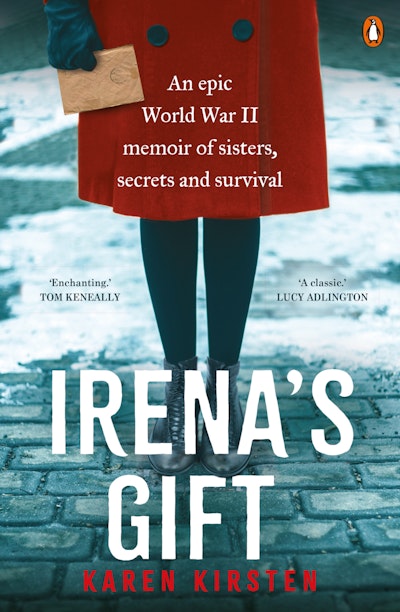

Karen Kirsten shares what it was like writing her family history and the research process behind her new book, Irena’s Gift.

Early in Irena's Gift, it is revealed that your mother’s past was hidden from her – when did she tell you the truth about her childhood?

When I was 13, I learned my Mum’s biological mother, Irena, was killed in Nazi-occupied Poland. I also learned that my Melbourne grandmother, who I adored, was not, in fact, my mother's mother – but rather her aunt.

Still, knowing that, it took me ten years to uncover the truth about Mum’s childhood, how she repeatedly escaped death, and how the woman I knew as my grandmother risked her life for her, as did many non-Jewish Polish people.

When did you decide to write about it?

It started with a promise I made to my grandmother after Schindler’s List. About a week after the movie came out, she asked me to take her out for dinner. For the first time, she talked about Auschwitz, how Dr Mengele would inspect her and other women. He would line them up for hours with his white gloves and whip, and she never knew when it would be her turn to be sent to the gas chambers. She told me things she had never told my mother.

A few years later, she let me interview her. On our last day, she said she worried what happened to her could happen again. She looked at me quizzically and asked, ‘You think someone will want to know all of this?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I do.’

That’s when I promised her I would write her story.

This book is based on your own family’s history. Why did you decide to share it?

Today, it’s easy for us to tune out and become numb to war if it is not affecting us directly or goes on for a long time. The world knew about Auschwitz. It was in the news, but for many seemed too horrible to be true. Others were indifferent.

I wanted to share a story of how war and displacement affected individual members of one family to humanise incomprehensible numbers. 1.1 million exterminated in Auschwitz is almost impossible to grasp, as is the fact that there are more than 35 million refugees in the world today.

But if you read in this book how my grandmother traded her wedding ring in Auschwitz for a scrap of bread to stave off starvation, this might move you. You might not see her as a nameless genocide survivor or refugee. And if you read how decades later, she would squat with me by rockpools along The Great Ocean Road searching for starfish, you might remember similar experiences with your grandmother. You might become more aware of people fleeing war and persecution today.

Was it difficult telling your family you were writing a book about your mother’s story?

It took me ten years to write, so they have had plenty of time to get used to it!

What was your research and writing process like for Irena’s Gift?

I started with my recorded family interviews which I verified. Then, I filled in gaps using deeply researched historical accounts, help from historians, archived documents, photographs, film footage, letters, newspaper articles, artifacts and diaries and recorded testimonies. The biggest challenge was incorporating all the research to build fact-based vivid scenes from pre-war Poland to post-war Germany.

To do this, I devoured and dissected gripping narrative nonfiction including Laura Hillenbrand’s Sea Biscuit, Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, Tracy Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains and Kevin Birmingham’s The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's Ulysses. I was fortunate to have access to wonderful teachers like Kevin Birmingham, and Australian-American Christina Thompson, author of Sea People, The Puzzle of Polynesia at Harvard Extension School in Boston where I live, as well as Alysia Abbott at GrubStreet who taught me about world-building, structure, and how to condense a very complicated story across three generations into a contemporary story of a daughter who wanted to heal her mother’s pain.

What do you hope that others can learn from your story?

I hope people are inspired by the remarkable people who saved my Mum - including my grandmother. If a few people hadn’t shown empathy and kindness towards my mother, I would not have existed to write this story. Despite the dehumanisation and horrible violence toward Jewish people, a few chose not to be indifferent. They chose to be upstanders, not bystanders.

Want more? Read a snippet, here.