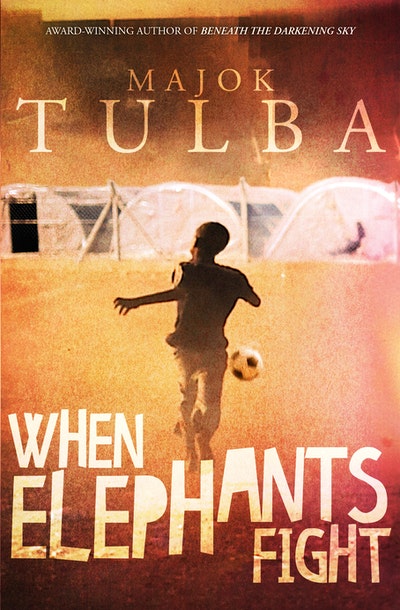

The Sudanese–Australian author reflects on the inspiration behind When Elephants Fight.

When Elephants Fight is based on Majok Tulba’s own experience of war in southern Sudan and his escape to a refugee camp. Here, we ask him about the importance of storytelling and the creation of a book that closely mirrors harrowing events of his life in Sudan.

Why do you write?

I am a storyteller from a long line of storytellers. When I write I am calm and in my Zen place.

What role did books play in your upbringing?

My background was in oral storytelling. The first time I saw a printed story was in the refugee camp and I was excited by the concept. Since coming to Australia I devour books and enjoy discussing and interacting with fellow writers and readers.

Can you tell us about the first story you remember writing, and reading?

I wrote a film script with lots of dialogue. It was set in Darfur and Nepean Hospital and was about a woman dealing with her traumatic memories of Sudan after arriving in Australia. I was a filmmaker–storyteller first and the novel writing came later. After learning basic English here in Australia, I enjoyed delving into The Power of One.

What compelled you to write When Elephants Fight?

The story of Juba and his plight is the story of so many young people in Sudan. I wanted people to hear about their situation and perhaps then to act to help.

In a creative sense, how did you come to know Juba?

Juba is a compilation of multiple friends I have known and young men I met in the camps and as refugees here in Australia.

Juba’s experiences are harrowing – almost impossible to comprehend from here in Australia. To what degree are the events in his life indicative of what was occurring during the latest civil war in Sudan?

The events were very accurate and if anything under-told. The reality is so harsh and shocking I could never reveal the depth of the senseless violence and degradation without having an ‘R’ rating.

When Elephants Fight is an intriguing statement as the title of your book. How did you settle on this title?

In Africa there is a saying that when elephants fight the grass suffers. Juba and his community are the grass to the elephant powers fighting for power in Sudan. Metaphorically, Juba and his family are the grass who suffer greatly as the great beasts rage across the country.

There is a moment in the book where Juba is robbed by a Dinka man, and he comments that in the refugee camp this man’s pride has departed him. Can you talk about this notion of pride being stripped from people, and how this affects them?

The people who make their way to refugee camps have been stripped of not only all their possessions but also their self-identity and self-value. They are often traumatised and often reduced to basic primal survival instincts. All the social niceties of civilised and dignified social interactions have been removed and behaviour returns to jungle-level interactions.

At the funeral of one of Juba’s friends, Juba laments that the earth doesn’t care: ‘It doesn’t say, I don’t want more. It doesn’t say, I’ve already taken enough. It just keeps swallowing.’ It’s a powerful sentiment, that after decades of war the earth remains indifferent to the suffering of people. Can you talk about your relationship with the land, the importance of the landscapes, the natural environment growing up in central Africa?

Not unlike the Aboriginal connection to the earth, I have a spiritual link to my homeland. I can wax lyrical about African sunsets and specific settings from my childhood that even memories of take me to a higher plane. I have to travel back because of the call of the land to renew my spiritual connection. It calls me back.

How has your perception of your homeland changed, now that you view it from a distance?

I still travel back for other reasons besides the land. I have family and friends there as well as my role in charity work. I run a program which enables women to become self-sufficient. We give them loans to purchase what they need to set themselves up. We also help girls with school fees, financial support for the needy and maternity services and clinics. I have a particular interest in the welfare of the young and the women as I saw my sisters, aunties and women in my community suffer so much. My perception of my homeland is that it is still a place that needs so much support.

Thankfully, among the horrors, the hunger, the disease and the ever-present dangers in Juba’s story, at moments he finds moments of intense joy, even love, throughout his journey. This brings us hope. What hopes do you have for those who remain in South Sudan?

If the fighting can be stopped the Sudanese people will rise capably and reclaim their land, and the wonderful promise that they are capable of in building a strong and fair society.