- Published: 3 April 2024

- ISBN: 9780143777403

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 384

- RRP: $19.99

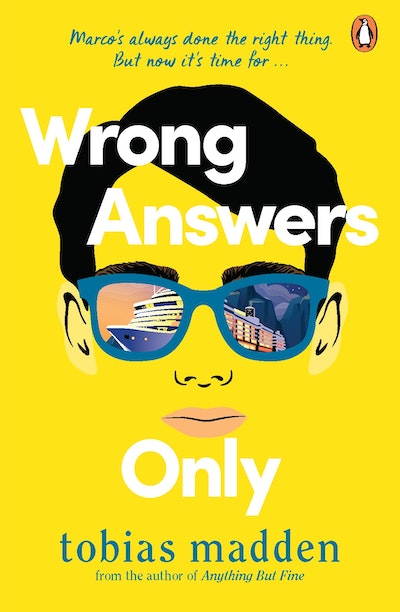

Wrong Answers Only

Extract

Nonna huffs, turning back to the orange laminate bench under the kitchen window. Her house is only a few blocks from the hospital, so we came straight here when the doctor discharged me, rather than driving all the way home. The second we arrived, she started crumbing chicken schnitzels.

‘He works too hard,’ she says, hunched over plates of chicken fillets, flour, beaten egg, and breadcrumbs.

The ‘he’ she’s referring to is, of course, me. And I don’t work too hard. I work exactly as hard as I need to.

My eyes land on the newspaper sitting on the floral tablecloth amongst plates of biscuits and fruit and a mountainous pile of zucchini slice. The paper is from the eighteenth of December – just over two months ago – but Nonna refuses to move it, most likely to streamline her bragging process when her church friends pay her a visit. The headline on the front page reads: St Peter’s High Achiever Tops the State.

Something hard hits me in the shin, and I swear. I whip around to glare at Leo, who’s plonked himself at the head of the table in Dad’s absence. He grins back at me, braces gleaming in the noon light streaming through the lacy kitchen curtains. ‘Just trying to distract you from your feelings,’ he says.

‘You’re such a little shit,’ I reply, reaching out to mess up his curly ginger hair. He bats my arm away and I slap him – softly – on the cheek with my other hand.

‘Leo,’ Mum snaps. ‘Not now.’

‘Marco started it!’

I scoff, folding my arms over my chest. I love my younger brother, I really do, but the constant presence of a twelve-year-old boy can test your patience sometimes. Especially when –

I reach out to open the passenger-side door and freeze. My heart stutters. The driveway sways beneath me.

I blink the memory away.

‘Hun,’ Mum says, leaning across the table to place her hand on my elbow, ‘are you sure you’re all right?’

My gaze drops to the newspaper again, and I frown down at the photo. The photographer used this weird wide-angle lens that I’m pretty sure is only meant for landscapes, so my head is kind of stretched on one side, and my hands look disproportionately long and alien-like. I’m usually quite photogenic – okay, fine, I’m very photogenic – but this is the worst photo of me in history.

‘Michelle?’ a deep voice calls from the hallway. ‘Mamma?’

‘In cucina!’ Nonna says over her shoulder.

Seconds later, the kitchen door swings open, revealing my dad in grimy blue overalls, panting like he ran the whole way here. His Central Highlands Ford name badge is still pinned to his chest pocket.

‘What happened?’ he asks the room, eyes wide. He leans on the doorframe to catch his breath. ‘I was in the middle of a wheel alignment and that shit of a kid Bill hired last week forgot to pass on the message and – Marco . . .’ He frowns down at me. ‘What the hell happened?’

‘I’m fine, Dad. I just –’

Heat flashes up my spine as I strain to reach for the doorhandle. I can’t move. My pulse thunders behind my ears. Why can’t I move?

‘Sit,’ Mum says to Dad, shooing Leo from his seat.

With a groan, Leo slides off the wooden chair and climbs onto the one beside me, managing to kick me in the shin again in the process.

‘Stop it, dickhead,’ I whisper, and he pokes his tongue out. Twelve going on seven, clearly.

Dad takes his seat at the head of the table, facing the bench where Nonna is preparing lunch.

‘Well?’ he asks, glancing from Mum to me and back again. ‘What happened?’

When neither of us replies, Leo says, ‘Marco’s afraid of university.’

‘Leo,’ Mum chides at the exact same time as I say, ‘I am not, you little –’

‘Leonardo.’ Nonna turns around to point a gnarled finger at my brother. ‘Silenzio.’

Nonna may be almost eighty-five, and she may be wearing an apron with a singing tomato on the front, and she may have shrunk at least six inches in the past year, but Sofia Di Mario is not a woman you want to mess with. Especially not in her kitchen.

Leo bites his lip and looks down at the table.

‘Come help Nonna with the chicken.’ She beckons him over to the bench, and Mum lets out an audible sigh of relief.

I glance back down at the newspaper. I unintentionally memorised the article when it was first printed. (It was impossible not to – it was all anyone spoke about for weeks.) It’s just the principal of St Peter’s gloating about my results and claiming a disproportionate stake in my achievements, followed by a short paragraph from the Dean of Science at Melbourne University, saying how excited she is to welcome me as an undergrad in the new year. Plus a cringeworthy – but painfully accurate – quote from me that says, It’s everything I’ve ever wanted.

‘Why isn’t Leo at school?’ Dad asks Mum, a hint of reproach in his voice.

‘I was going to drop him off on my way to the train station with Marco, but then . . .’ She purses her lips and looks over at me, her eyes brimming with concern.

‘I had a . . .’ (I refuse to call it what everyone else is calling it, but I don’t how else to describe it) ‘. . . thing.’

Mum jumps out of the driver’s seat and skirts the bonnet. My chest cramps. I can’t breathe. I can’t –

‘What kind of thing?’ Dad asks.

‘A panic attack,’ Mum says gently, placing her hand on mine. I pull it away and clasp my hands under the table.

Dad’s bushy eyebrows furrow. ‘A panic attack?’

‘It was nothing,’ I say, desperate to minimise this conversation. ‘I’m perfectly fine.’

My ribs are in a vice. I’m going to vomit. The driveway tilts again and I stumble into the car door.

Dad’s frown deepens. He’s giving me the exact same look he gave me when my cousin and I simultaneously came out to our entire family in Nonna’s backyard one Christmas: Concerned. Caring. Completely confused.

‘Are you nervous about O-Week?’ he asks. ‘About uni?’

Mum clicks her tongue. ‘It’s not nerves, Andrea –’ (that’s Dad’s name, like Andrea Bocelli, the opera singer. Just don’t ask him if he got picked on at school for having a ‘girl’s name’ unless you’ve got a solid four hours to spare) ‘– it’s anxiety. They’re very different things.’

Dad doesn’t believe in anxiety. Everyone has worries, he always says. I don’t know why people need to make such a big deal out of them! And in this case, I have to agree with him. It wasn’t a panic attack. And I do not have anxiety.

‘He was under an enormous amount of pressure last year,’ Mum goes on. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s dealing with some sort of anxiety hangover from his exams or something.’

She worked full-time as a nurse until she had my older brother, Dante, and she went back to doing a couple of shifts a week at a maternal health clinic when Leo started school, so she takes this kind of thing (her son being rushed to the hospital in an ambulance) pretty seriously.

‘Or maybe,’ she says, shifting her gaze to me, ‘the combined stress of always having to be the best at every single thing you’ve ever done has finally got the best of you.’

I roll my eyes and look away, watching Leo as he dangles a piece of raw chicken over a bowl of beaten egg.

Nonna gives his hand a little slap and says, ‘Nella farina. In the flour first, bello.’

I turn back to Mum and Dad. ‘I probably just had too much coffee this morning.’ I run one hand along the perfectly straight side-part in my hair. ‘I’m not nervous. At all. I’m excited, honestly.’

And I am. Honestly. I woke up this morning already thinking about my new timetable. Meeting my lecturers. Being surrounded by people who want to learn, instead of a bunch of boob-obsessed jocks like the St Peter’s boys. And I’m not a nervous person. If anything, I’m the opposite. But then . . .

I drop to the gravel at my feet. Pain lances through my chest. I grip my heart with both hands.

‘Well,’ Dad says, rubbing at a grease stain on his hand, ‘if you feel fine, you can get the train down this afternoon.’

‘Or . . .’ Mum adds, giving him a look.

He clears his throat. ‘Or . . . we can drive you down to the dorms tomorrow if it’ll help with the nerves?’

‘It’s not nerves, Andrea,’ Mum says.

‘Anxiety, then. Whatever.’

‘It’s not anxiety,’ I press, and Mum gives me a look this time.

‘What do you think, hun?’ she says. ‘We’ll drive you down tomorrow?’

Sweat pricks my palms. Why does it suddenly feel like it’s a hundred degrees in here?

‘Marco?’

I swallow. ‘I’ll get the train down this afternoon. You guys don’t need to come. I’ll be fine.’

And I will be. I’ve been working towards this moment for thirteen years. Longer, if you count from when I started playing (and winning) Operation at age three, or in kindergarten, when I surgically removed the stuffing from all of Dante’s teddy bears in the name of science. I’m not about to let . . . whatever happened this morning stop me now.

Mum inhales loudly, and I can feel her frowning at me.

‘I’m seriously okay,’ I say, keeping my eyes on Dad. ‘Better than okay. I’m great. Can we just go?’

I push my chair back from the table and stand up, my head spinning a little as I do.

Dad stands with a grunt. ‘Let’s get you to the station, then.’

‘We’ll all go,’ Mum says. ‘Give you a proper send-off.’

My stomach tumbles. My ribs clench.

‘But the chicken,’ Nonna laments. ‘We haven’t eaten.’

‘Please, Mum,’ Leo groans, his hands covered in breadcrumbs, ‘I’m starving.’

‘Wash your hands,’ she says to him. ‘Quickly. I’ll drop you at school on the way to the station.’

‘But –’

‘Now.’

To the less-than-soothing soundtrack of Leo whinging about school and Nonna protesting about sending me on the train without lunch, we eventually make our way out the front. Dad opens the white, wrought-iron gate as Mum herds Leo and Nonna into the back seat of her station wagon.

‘I’ll meet you at Wendouree Station?’ Dad asks, climbing into his ute.

‘You don’t have to come,’ I reply. ‘Everyone is being exceedingly dramatic.’

‘We’ll see you there,’ Mum says to Dad, ignoring me.

He shuts his car door and turns on the ignition. Mum gets in her car, leaving me standing on Nonna’s concrete driveway, alone. I push down the strange mix of emotions rising from my belly and reach for the passenger-side door. As my fingertips brush the metal handle, my breath catches and I freeze. My fingers tremble. My feet turn to lead, and I –

Oh, no . . .

No, no, no. This can’t be happening. Not again.

‘I – I can’t . . .’

Nonna’s front yard sways.

The cypress trees beside the driveway fold in on me.

I look down at my shoes, my heart clattering against my ribs.

‘Bello?’ Nonna says, winding down her car window. ‘Stai bene?’

Mum jumps out of the car. ‘Hun? Are you okay?’

‘Marco,’ Dad says, already beside me, but somehow far away at the same time. ‘What’s wrong?’

My lungs are burning. My pulse is deafening.

‘I think you should lie down.’

‘What’s happening?’

‘Bevi un po’ d’acqua!’

‘Take him inside.’

The four voices sound like they’re calling from the end of a tunnel.

‘Is he having another one?’

‘I don’t know, hun.’

‘Get a paper bag!’

‘Ha bisogno di acqua!’

Frantic hands guide me back into the house. Every step is an effort. Every breath hurts.

‘Leo, fan his face with this.’

‘Marco, are you all right?’

The world tips and I land on something soft. My vision is all fuzzy at the edges.

‘Breathe.’

‘Deep breaths.’

‘Relax, bello.’

‘Mum, is he okay?’

‘I’m –’

‘Don’t try to talk, hun. Just breathe.’

I go to inhale, but my lungs are being crushed. It hurts so much I can barely even think.

Someone passes me a brown paper bag. ‘Here, breathe into this.’

‘Vai tranquillo. Slowly, slowly.’

I breathe into the bag. It smells like mushrooms.

‘It’s okay,’ someone says. ‘You’re okay.’

I stare up at the four blurry faces. Mum, her auburn hair falling in curtains around her face. Dad, his dark eyes peering down at me. Leo, lips pulled to one side. Nonna, frowning, shaking her head.

‘Just breathe.’

At first, breathing into the mushroom bag only makes my pulse race faster, but eventually – eventually – the blood stops pounding past my ears. The muscles in my chest relax. My vision sharpens, and the room expands around me. I feel exhausted, like I’ve run Lake Wendouree on a forty-degree day (which, for the record, I have done, and will never be doing again).

‘Marco,’ Mum says, kneeling down beside me. Dad, Leo, and Nonna all huddle around my feet at the end of the brown leather couch. ‘Are you –’

‘I can’t go,’ I cut in, still out of breath.

‘We don’t have to go yet,’ Dad says. ‘The trains run all afternoon.’

‘I don’t mean the train,’ I say, trying – and failing – to push myself up to sitting. I’m all woozy, like I’ve just stepped off a roller-coaster at Movie World. ‘I mean Melbourne. Uni. I can’t go.’

Dad frowns. ‘But –’

‘Andrea,’ Mum snaps, then cups my hand in hers. ‘Let’s talk about it later, hun. You need to rest.’

‘Do I get to miss school?’ Leo asks, and Nonna slaps him on the shoulder.

Dad pulls his phone from the front pocket of his overalls and heads into the hallway. ‘I’ll tell Bill I need the afternoon off.’

‘Lavora troppo,’ Nonna mutters, shaking her head. ‘He works too hard.’

‘You should have a nap,’ Mum says to me, stroking my hair. ‘We’ll give you some space.’

I nod, forcing a smile as she ushers Nonna and Leo out of the room.

I don’t know what the hell is going on here, but it’s clear that I’m going to need a lot more than a nap to fix whatever this is.

Wrong Answers Only Tobias Madden

Marco's always done the right thing. But now it's time for wrong answers only.

Buy now