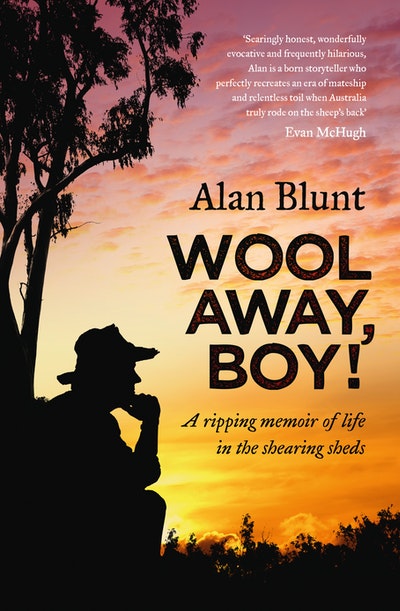

The son of a shearer, Alan Blunt spent his teenage years in the woolsheds of the 1950s and 60s. And for thirty years he continued to work in outback Queensland, starting as a rouseabout and eventually working his way up to wool presser. Always a keen observer of character, in the evenings he recorded portraits of workmates by the light of a pressure lamp, filling one foolscap pad after another.

In his memoir Wool Away, Boy!, Blunt chronicles all the larger-than-life personalities he met: the misfits, romantics, larrikins and psychopaths. With irrepressible wit, he captures the voices of these men and brings to life a golden era of shearing.

As the book meanders through the decades, from his unique perspective he also chronicles a period of enormous social change in Australia. Straight from the pages of Wool Away, Boy!, from the chapter entitled ‘The Times They Are A’Changing’, below Blunt details a confronting return to the shearing sheds in the early 1980s, after several years away.

I found the comforting familiar woolly smell and the pungent stench of the sheep yards remained, but the clickety song of the manual wool press had given way to the noisy, fume-spewing mini-motors powering hydraulic presses. The contract rate of pay was less but the work was considerably easier. I resented the cut in earnings but appreciated the lighter work load, as my muscles and joints were apt to remind me that I was getting a bit long in the tooth for really heavy yakka.

Ten years had seen dramatic social change. While most sheds were still fully unionised, I regretted that workers’ solidarity and team spirit were dissipating. In the 1970s, Gough Whitlam, a progressive Prime Minister, had gone to bat for the workers, dramatically increasing wages. As a result there was a lot more ready cash about, and more shed workers had cars with radios and tapes blasting rock’n’roll at full volume on the roads Slim Dusty used to own.

‘Mary J’ had also come to stay. And in some sheds hostility ensued between young dope-heads, who claimed the right to blast the shearing board with head-banging sound, and older men who found the cacophony stressful and disrupting to their traditional quiet work rhythm.

Most young woolshed workers had abandoned the restful, money-saving weekends in the bush – spent reading, yarning, letter writing to Mum or a girlfriend, listening to the races, playing cards, fishing and hunting wild pigs and roos – for the thrills of getting boozed and stoned and the prospects of a weekend’s shagging. The ACTU, led by Bob Hawke, had won ‘equal pay for work of equal value’, which was funding female independence, and the advent of the Pill had decreased the fear of casual pregnancy and increased sexual adventurism. Some men now ‘shacked up’ in town – short- or long-term – and it could be said that the hit song, ‘I won’t go hunting with you, Jake, but I’ll go chasin’ women’, had become the theme song of a generation of young bush workers.

Although cars, telephones, electricity, diesel engines, radio and air-services had already modernised outback living, it wasn’t until the 1970s that the work practice, mateship, ideals and traditional way of life of the shearing shed intrinsically changed. While female shearers and Kiwi shearers and their women rousies were yet to become a significant part of the industry, I realised mournfully that during my absence most of the elders had been marched to death or retirement by the remorseless drum of the old enemy – Father Time. The traditional shearers’ campfire yarning, joking, chiacking and debating over politics, general news, women, sport and family were morphing from culture to folklore.

My heart was with some old-school shed overseers and shearers who battled to hang on to the quiet values of the way of life they felt comfortable with. Men of my own generation – hardy professional shearers of middle years who might come from as far away as Sydney’s western suburbs or rural Victoria to support and educate a family – could find themselves shearing alongside tattooed, ear-ringed long-haired youths who often only shore enough to pay for their indulgences. Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, backed by the relentless blast of tape recorders, was becoming the mantra of the shearing boards.