- Published: 27 June 2023

- ISBN: 9781760899639

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $32.99

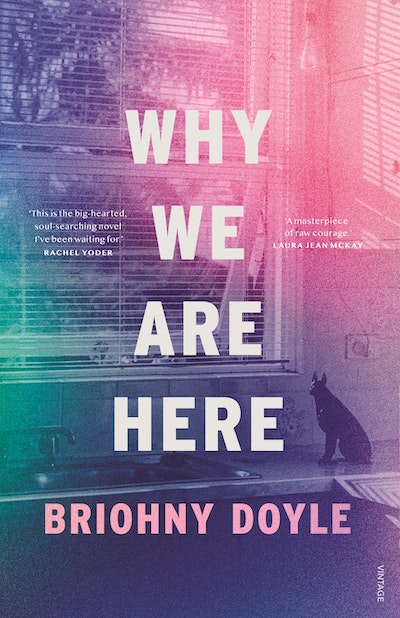

Why We Are Here

Extract

In the aftermath of Him I’d found the outside world’s ongoingness obnoxious, but I was wrong. External reality may have been cruelly incongruous, but it was still generously there. Like the freezer-ful of lasagnes that arrive the week someone dies. No one wants to eat them, but as long as they exist starving is a choice. Life’s ongoingness made retreating a position. I was a Thoreau of grief, committed to condemning all of ‘slimy, beastly life’ as long as sympathetic society and freshly baked cookies were walking distance from my pond of tears.

When Highborne locked down I saw my fear and confusion mirrored in the puffy eyes of friends and colleagues. It did not feel like solidarity but fresh injustice. I returned to bedroom life, inconsolable again.

My housemate and I watched the press conferences. We did impersonations of politicians and journalists. Went for awkward masked walks along the creek. Kept strange hours. We threw ourselves on the floor. My housemate mounted corporate class action suits from his bedroom. I reassured students in the grid of squares that used to be a classroom. I gazed across the screen, past their dejected faces.

At the start of the pandemic Dad—missing the newsroom—called regularly to break each story to an audience of one. Soon, the tenor of these calls shifted from thrill to dread.

I know we’re not phone people but let’s keep in touch, okay? I might go spare if this lasts much longer, Dad said.

An already isolated person needs the banalities of everyday interactions. A chat with a butcher or barfly is the difference between a day that’s worth living and one that’s not.

Soon Dad mostly called when he needed me to arrange an ambulance. In broken syntax and grunts he communicated how he felt safer in hospital now. In hospital there were fluids and vitamin B, oxygen on tap, three square meals delivered by nurses who chatted as they checked charts and changed sheets.

In the immediate aftermath of each hospital discharge, Dad insisted he had it under control, and to some extent this was true. He already knew how to drink. He soon learned to summon his own ambulance when it became clear he couldn’t drink any more.

Some nights, though, at the eloquent peak of a bender, Dad called to tell me that, in fact, he simply wanted to die. Is that okay?

Yes, that’s okay, Dad. I’d rather you live but I’m not forcing you to be alive.

Well, I’ll just die, okay? Is that okay with you?

Okay, I sobbed. I love you and I really hope you don’t die.

On these drunken phone calls Dad was not in a subjunctive mood. When sober, he either denied the conversations had taken place, or implied they’d not been serious.

Ha fucking ha, I said.

I called his doctor. I called aged care services. I called a man about an oxygen tank. I experienced the disconcerting reversal of being the adult who people listen to as the parent becomes a barely tolerated child. I looked at apartments within a five-kilometre radius of my own home. Perhaps I could buy one, put Dad in it for his final years and then move in after. Dad had too much money left over from his redundancy and superannuation to qualify for public housing, but too little for private rent. He was living in Goldtown on my mother’s kindness, in a bungalow in her garden.

I’m perfectly fine here, Bop, Dad slurred.

Ambulances pulled up on the nature strip in front of my mother’s house, flattening the native flowers she’d planted there.

Every time I tell a heterosexual man about my dad in my mother’s bungalow, they go quiet and thoughtful. Which ex-girlfriend would let them move into her backyard if times got tough?The one you have a child with, I insist. But even childless men already have a name in mind.

Every time I tell a woman about these men with designs on our backyards, the response is exactly the same.

No fucking way!

I would have said the same thing once, but He is welcome in my backyard. By the fig tree stump, beneath the vine-choked frangipani, in the garden of weeds. Please please please just show up in my backyard I won’t ask any questions.

Why We Are Here Briohny Doyle

'A masterpiece of raw courage – shot through with the humour, heart and more-than-human understanding that is central to Doyle's work.' Laura Jean McKay 'This novel has no right to be as funny as it is.' Gina Rushton Why We Are Here is a love story revelling in the beauty and solace of the natural world, embracing the bonds between humans and celebrating the empathy and wisdom provided by dogs.

Buy now