Ten authors discuss what To Kill A Mockingbird means to them.

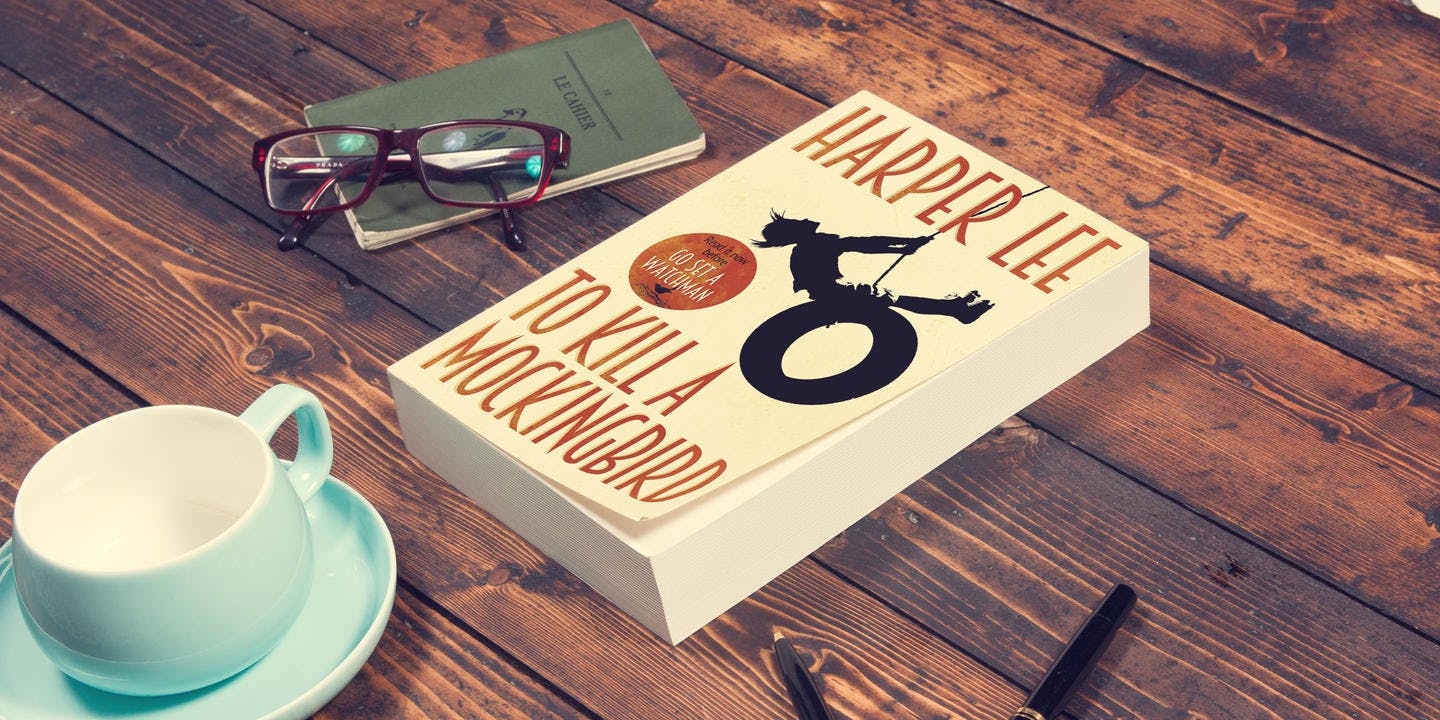

Go Set A Watchman was Harper Lee’s first novel since To Kill A Mockingbird, which was published in 1960 and has been an enduring favourite ever since – an esteemed literary classic that also consistently tops popular votes for the best novel of all time. Go Set A Watchman returned us to the same world, as a now-adult Scout Finch made her return to Maycomb County.

In the final days of the countdown to the novel’s worldwide release in July 2015, we asked ten top authors for their personal stories about To Kill A Mockingbird and that unique book’s place in their lives.

Deborah O’Brien – author of The Trivia Man

Ever since I first discovered To Kill A Mockingbird as a teenager, I’ve returned to it every few years and always found something new and wonderful within its pages. For me, this novel is as near to perfect as a book can be. Its powerful themes are expressed in lucid yet lyrical prose, and its cast of characters is so well-drawn that you live every moment alongside them. And where would you find a better fictional father than Atticus Finch, or a more mysterious, misunderstood figure than Boo Radley?

Annie Barrows – author of The Truth According to Us

Some books change the world, and I think To Kill A Mockingbird is one of them. Its innovations have become our archetypes: we understand small-town America in the thirties because of this book, we understand the inheritance of racism because of this book, we understand the painfully incremental progress of justice because of this book. But To Kill A Mockingbird was made, and when I think of its construction, I’m awed most of all by the rendering of Scout, Jem, and Dill – the first truly respectful portrayal of children in a book for adults.

Candice Fox – author of Eden

I encountered To Kill A Mockingbird the way that most people do; in high school. And I think you can see what the book meant to be by examining the attitudes that I brought to the reading of it. I was eager as the book was being handed around the room, and when I got the tattered, yellowed copy that would be mine for two months I felt my heart sink.

There was a tree on the front cover, and nothing else. Oh, thrilling start. The author and the characters had names I'd never heard of. Atticus? Sounds like some old-school Roman philosopher dude who probably drones on too much about stuff I won't understand. Scout? She's a girl? The main character is a little girl. Oh this is just fabulous. I hurled the book to the bottom of my bag and spent the first three weeks of the unit pretending I'd read it. My mother made me read it.

And it's funny now, realising that those prejudices that I brought to the book, my own angry certainty and its slow and wonderful wearing away, are exactly the themes that the book deals with. I think it was the last time I picked up a book and thought I knew it before I'd opened it. The same trust, courage and wonder that Scout demonstrates in the book are things I had to learn by being surprised at how much I cared for Lee's characters and their world.

Debra Oswald – author of Useful

I first loved To Kill A Mockingbird with all the intensity of my teenage self, grateful to find such a passionate, vivid and sometimes distressing book. And now it’s always there in my mind as an example of a novel that manages to combine a muscular story, heartbreak, humour, outrage, delight, moral doubt and love with such compassion and generosity.

Kate Forsyth – author of The Beast’s Garden

To Kill A Mockingbird is a touchstone book for me, a novel I return to again and again with love and wonderment. It always feels like a perfect novel – so simple, so effortless and yet so powerful and true. Each time I read it, I am humbled by just how good it is – in all senses of the word – and hope that one day I might be able to write something halfway as brilliant.

Martin Flanagan – author of The Short Long Book

In recent years, I have been involved with the half-Israeli, half-Palestinian AFL Peace Team. The head of this quixotic adventure was a Melbourne lawyer, a Jewish Australian named Henry Jolson. Henry was tall and good-looking and intrinsically modest. He had been a talented footballer in his youth; good enough, I am told, to play AFL. Perhaps because he was tall and handsome and strong, Henry didn’t have a lot of the fears that other people have. He believed there could be an honourable resolution to the conflict in the Middle East. I told Henry’s daughter one day that he reminded me of Atticus Finch. She didn’t know who Atticus Finch was. I said, ‘You’ve got to read To Kill A Mockingbird.’

Tegan Bennett Daylight – author of Six Bedrooms

To Kill A Mockingbird was for me the first thread in the lovely weave of literature between Harper Lee and Truman Capote. Knowing that the character of Dill was a portrait of the young Truman led me to his writing, and his writing in turn led me back, again and again, to Mockingbird. It’s amazing that two people who were childhood friends could have made some of America’s greatest literature between them. I like to think of them playing together in the streets of Monroeville, beginning the storytelling that would result in the books that we’re still reading and loving today.

Fiona McIntosh – author of The Last Dance

Dragging myself back to the late sixties in Britain . . . To Kill A Mockingbird was read to us school, and while the understanding of civil rights went over my head I remember imagining myself to be Scout. I too was living in an era when kids were left to themselves to make their own fun, and I too was a girl who was being required to grow out of her tomboyish ways. I could picture Scout’s life because of the vivid storytelling and I loved her freedom, her courage and especially her father, who became a hero for me.

Georgina Penney – author of Fly In, Fly Out

Casual racism was more abundant than water in the local dams when I was a kid in country Australia. When I was eight I overheard the town mayor calling an aboriginal kid the ‘N’ word in public. It felt incredibly wrong but as a child myself, I couldn’t articulate why. Then I read To Kill A Mockingbird. Suddenly I had an adult, Atticus, and two children like me confirming my suspicion something was broken. It gave me the words and the strength to speak up. Today it sits in my bookcase, representing a rock solid foundation of my social conscience.

Nicole Alexander – author of Wild Lands

Ultimately a story about the loss of childhood innocence, everyone who reads To Kill A Mockingbird will take something different and undoubtedly inspirational from it – the innate goodness of Atticus Finch, the mind of a nine-year-old girl, the depression years in America’s south. Transporting us to the origins of human behaviour, for me, Harper Lee shows us what a moral society actually means.