- Published: 2 March 2021

- ISBN: 9781760897789

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 416

- RRP: $32.99

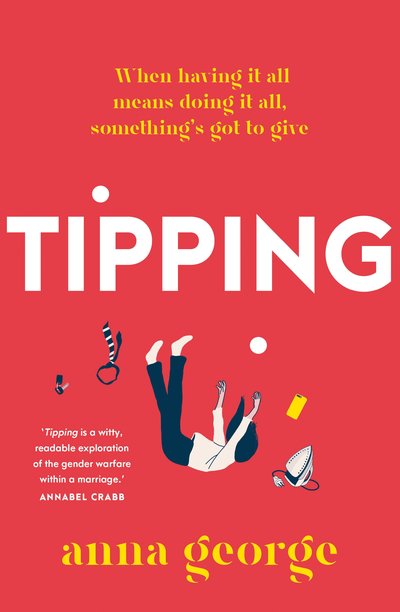

Tipping

Extract

1

Liv

Forty-five, married and healthy, Liv Winsome was increasingly dismayed by her lot. Life wasn’t as she’d imagined it twenty years, two degrees and three children ago. Only moments earlier, her husband of almost two decades had forgotten her. With a jaunty flick of his wrist, Duncan had clicked his keys at their car behind him. Sitting in the car, finishing a call, Liv had taken a second to understand and try the handle. Then she’d clambered across to the driver’s-side window and thumped. She’d called out. This can’t be happening, she’d thought, pushing buttons. But it was. Duncan and Jai, one of her fourteen-year-old sons, were dashing towards the office at Carmichael Grammar, without her.

The morning was getting warmer, and the car park full. Sunlight was pouring across the roof of the recently completed Wellbeing Centre. Other families had already arrived, presumably in their full contingent, to watch their beloveds play sport. Their cars, mostly SUVs, the odd sedan or station wagon, looked in reasonable condition. Probably nothing faulty about any of them – no dodgy latches or hidden defects. Newly bought, the Winsomes’ car was second-hand but luxe for them. Liv had spent the last few weeks of summer researching, avoiding suspect airbags and dud transmissions. Not one review had mentioned this.

Pressed up against the glass, Liv searched beyond the car park to the school’s immaculate sportsgrounds. Though her three sons attended Carmichael, she didn’t recognise a single, sweaty child. She tried Duncan’s phone. She tried Jai’s phone; but, of course, it was still off – and, she remembered, in her handbag. She tried Duncan’s again. Often, when she rang, her husband’s phone was on silent, or in a distant pocket. She peered into the brightening sky. Usually, she didn’t mind Duncan’s not answering. But, this morning, it was getting hot.

Children were locked in cars, she thought. Not adults, not wives.

Duncan did have form, though. When the twins were babies, she and Dunc had gone on a much-needed short break interstate. Taking pity on them, a close friend had set them up with staff travel. Duncan and Liv were separated in the terminal as they waited on their seat allocations, and she and the twins had boarded the aeroplane without him. Liv was breastfeeding the boys then, and in a nonstop state of exhaustion. With a baby at each breast, she’d sat at the rear of the plane, near the toilets. Liv had fretted when she hadn’t seen Duncan board. It was only as the flight attendants performed their final checks that one of them whispered, ‘Are you Liv?’

‘Yes.’ She smiled above the slurping babies.

‘Duncan wants you to know he got a seat.’

‘Thank you.’ Her relief was instant.

‘Up the front.’

‘Oh.’ Liv craned her neck to look far down the aisle.

Polite, with a ready grin, Duncan was the sort of man other men liked, women befriended and old ladies called ‘perfect’. Fifty minutes later, when the flight ran out of food, Liv was offered an apple by the apologetic staff. When the plane landed, Liv learnt that Duncan had enjoyed an egg and bacon roll, a blueberry muffin and an orange juice. For the entire flight, Duncan hadn’t thought to check on her or swap seats. Or nurse a baby. It was as if he was travelling alone, which, to be fair, he usually did. He’d felt terribly bad afterwards, when he heard about the apple.

A corkscrew of panic twisted in Liv’s chest. Though autumn had begun weeks ago, it was expected to reach an unseasonably warm thirty-two degrees today. When they’d left home, it’d been twenty-six. For their short, tense trip, Duncan had set the air conditioning on high, but the air in the car was no longer cool. Liv clambered back into the passenger’s seat for a better view of the oval. Two sets of boys in footy jerseys were deep in a game. Liv thought she recognised one of the pink-cheeked midfielders – someone’s giraffe-like big brother. She waved. But no one was giving her, or the car park, any thought. She reassessed the multi-level buildings, the curving driveway. Past the ovals, the buildings appeared to be empty. Between the buildings was a glimpse of the bay. Usually the water calmed her. Simply looking at a poster of the sea made her feel better. But looking at the water this morning was not helping.

Duncan had only been out of sight for a minute or two, but it seemed like twenty. Already, the car was getting stuffy.

Liv elbowed the horn.

Twelve hours earlier, the Winsome family’s current woes had begun with a phone call. It was 10.40 pm on a Friday, and Liv was driving home from Oscar’s disappointing representative basketball game in Bendigo. The standard of these games could be quite high, as each club chose their best players for the teams. But tonight’s game was a shambles. After giving Oscar a light roasting, Duncan had fallen asleep. Oscar had sung himself to sleep as well by the time the phone rang. Liv assumed it would be Jai, the team’s star point guard, home sick with a sore throat. But the number was unfamiliar. She’d pressed the button on the steering wheel and a woman’s voice had burst into the dark cabin.

‘Is this Jai Winsome’s mother?’

‘Yes.’ The silence gaped like a ravine. ‘Is he okay?’

Liv eyed Oscar snoring, open mouthed, in the back seat.

‘That’s a matter of opinion.’ The woman’s tone, while nasty, didn’t suggest tragedy.

‘Who is this?’

‘Jilly Saffin, Bella’s mother.’

Liv tried to recall either the woman or the girl. Had Bella started in the twins’ year at Carmichael in Year Three, five years ago? The Jilly that Liv could remember was fine-boned, with ironed, yellow hair.

‘What’s this about?’ Liv turned down the volume.

‘Tonight, Jai and that Blake Havelock . . . posted . . . the things they’ve written . . .’ The woman’s voice was breaking up but Liv caught her drift. ‘Bella . . . and Jai’s girlfriend, Grace . . . humiliated . . . and some girls are only twelve!’

‘Jilly, Jai won’t have done any of that,’ said Liv. ‘He’s sick.’

The younger of her twin sons, her secret favourite, was also a decent, sensitive child, who didn’t have a girlfriend.

‘Blake told his mother. They did it together, all right. I just got off the phone with her.’

Liv pictured her son’s best friend: narrow, stooped and wan. Oh, Blake. A complicated kid, he wouldn’t have been her choice for the job. Liv first met Blake Havelock when he was seven years old, and even then he was trying. It was day one of Year Two and, slyly, he’d been kicking balls over fences and up-ending rubbish bins. His chatty mother, Stella, had quaffed coffee while laughing wildly at Liv’s jokes. Hard not to like, despite her crafty son, who, unfortunately, Jai had loved on sight: ‘Mum, he’s so fun!’

Liv could remember the Saffins better, then. Jilly Saffin was a fragile woman with a retired, compliant husband and an odd set of children: Bella (frumpy, kind, reserved), aged fourteen, and a son (sporty, social, popular), aged sixteen, who’d been sent to the Australian Institute of Sport in Canberra.

She tried to follow the threads of the conversation. ‘But Stella’s in the Northern Territory.’

‘That was her excuse. What’s yours?’

Liv swallowed. Was it for her to have an excuse, or simply for her son? And what of her napping husband? ‘Jilly, I’ll look into it.’

She’d ended the call and planted her foot. ‘Duncan?’ she whispered. ‘Wake up. Where’s your phone?’

Not one person was responding to the horn.

Liv watched two boys running for a loose ball, from opposite directions, and she winced. Nearer the car, on the driveway, three girls in Carmichael sports uniforms sashayed past. Four boys propped on a fence took their eyes off the game to yell and gesture at them. The boys were from the opposing school: some inner-city Grammar. One girl tugged at the hem of her netball skirt. The others grew pinker with each step. Laughing, the boys shoved each other until the smallest of them fell.

Like a demented child, Liv continued tooting.

Last night, as paddocks dashed by, it’d seemed to Liv she was constantly rushing. Constantly time-poor. Constantly exhausted. That morning, she’d risen at six to ready the boys for school and herself for work. At eight, once the boys had left, she’d driven across town to interview the former workmates of an injured truck mechanic. Around two, hot and hungry, she’d interviewed their defensive motor-head boss. By six, she was rushing home again to pick up Cody from Harry’s house and make veggie burgers.

She looked to Duncan, who was hunched over his phone.

‘This Grace girl . . .’ he said. ‘Crikey. She really fourteen?’

In the rear-view mirror, she glimpsed Oscar, still asleep. You could just make out his wispy moustache.

‘Put it away,’ she whispered.

She rushed, she supposed, to fit everything in and keep everyone happy. As if her husband’s and children’s happiness were her KPIs. Of course, Duncan’s happiness was ultimately his responsibility, but Liv did what she could, and much of the boys’ happiness fell to her. And her boys were happy – or so she’d thought. Their happiness was measured in activities and grades and goals, friends and haircuts and shoes. Each day, she attended to their breakfasts and school lunches, their clean washing and stainless steel water bottles, their home-baked after-school snacks and healthy, colourful dinners. Each week, she scheduled the boys’ basketball training (for two teams, their local, domestic team and representative team) and their football games, clarinet/trumpet practice and maths tutor, swimming lessons and play dates (for nine-year-old Cody). Until recently, she’d patched their six knees, cut their thirty toenails and sponged their countless stains. She still chased a filthy Cody around the backyard with a hose. Listened to his eternal, illogical stories. Stemmed his bloody noses. She washed the boys’ bed linen, admittedly not often enough, and hung their towels. Nightly, she scrolled through the twins’ messages and monitored their screen time. (She’d never seen anything alarming. Not like this.) To preserve her sanity, and her marriage, she organised annual holidays, dinners with friends and date nights. Twenty-five years ago, she was a high-achieving student, and today she was a high-achieving mother (and wife). A super-doer. Or so she’d thought.

She’d been living, she realised, as if one day someone was going to grade her efforts, and that A-plus would make everything worthwhile.

Arriving home around 11.30 pm, Liv had been relieved to see the house lit up and Jai sprawled on the couch. He was watching the Milwaukee Bucks play the Toronto Raptors, with one hand on his phone, the other in Duncan’s chocolate stash. Stirred by the ceiling fan, shreds of silver foil danced about the orange carpet. The carpet, like the flat-roofed house, was only a few years older than she was. Built in the early 1970s, their house was large and airy and in need of updating. And she loved it. Its unpretentiousness. Its liveability.

She surveyed the rest of her tired home as if on the lookout for a sniper. You can do this, she told herself.

‘Hi Mum, did we win?’

Jai was smiling his usual smile, which involved most of his face. His large white teeth were chocolatey. He seemed better. She shook her head.

‘Did Oscar score?’

‘Nope.’

She studied him for signs of knowing. His eyes, like hers, were oversized, dappled hazel and rarely deceitful. He swept his hair across his forehead. She took in the sprinkling of freckles across his nose. His throat, where his glands were down. Yes, he looked better. He also looked like the sort of boy she would’ve fancied at high school, and therefore avoided. Fortunately, he and Oscar seemed unaware of their looks.

Duncan entered then, carrying Oscar’s basketball backpack. Confusion was scrawled on his face, and something else – horror, or awe? Oscar’s expression, too, was complicated.

‘Why’s everyone looking at me funny?’

Liv abandoned the horn for her phone once more. Dialling, she reminded herself that this school was run by professionals who fell over themselves to help. The teachers at Carmichael, though not perfect, were the best money could buy, which meant highly engaged and terribly responsive. If you emailed them at 7.39 pm on a Sunday with a homework or excursion query, you’d have a response by 7.43 pm. The office staff were similarly efficient.

Twenty seconds later, her call rang out.

No doubt the office was having an especially busy Saturday.

Liv remembered then a study, done in the 1960s, after a woman was murdered outside her apartment in New York City. Thirty-odd people in the surrounding apartments had heard her screams, but no one came to help, apparently. Why? It turned out, because everyone assumed someone else would . . . if it was necessary. The study found that if you wanted to be helped or rescued, it was optimal for fewer than four people to be nearby. One was best.

On and around the ovals, Liv could see more than sixty people.

She was stuffed. She pressed the horn again, long, insistent bleats. Perspiration dotted her cheeks. Eventually, a lonely winger turned in the direction of the car. A breeze lifted his fringe from his eyes. When she tooted again, he took a step towards the car park and she beamed; but then, in the midfield, a boot connected with the ball, sending it high and his way. And he was off.

The TV was black and Jai was perched on the couch when Liv said, ‘You wrote that Grace Charters loves cock.’

‘I did?’

Jai took Duncan’s telephone and flicked through the images. He looked, at most, puzzled. His gaze lingered on the one of Grace, his apparent girlfriend. Then he flipped through the others, while Liv talked. As he listened, his eyes flared, but not with major distress or mortification. Watching over Jai’s shoulder, Oscar’s eyes were wide, yet wounded. This girlfriend caper seemed new to him too.

‘What do you have to say?’

Duncan shot Liv a go easy look as he switched off lights and the fan. For ten whole seconds, they sat in vacuum-sealed silence as Jai seemed to process the night’s developments. Then he returned the phone.

‘They’re not the best of Bella,’ he said softly.

Liv frowned at the photographs of girls in various modes of dress, ranging from school uniforms to barely there bikinis; thankfully, none was topless or explicit. But, beneath each image, foul comments vied for attention, like scrawls on a toilet door. Girls were given ratings of 3 out of 10, called ‘skanky ho’s’ and ‘ugly bitches’ . . . Liv recognised many of the kids’ handles: these were boys from school. Her sons’ friends and acquaintances; the children of friends and acquaintances.

Liv’s stomach roiled.

Jai drew his heavy eyelids down. Sometimes, Liv thought her handsome sons resembled thoughtful lizards. But, tonight, this son’s silence was baffling her. She’d been chatting with her boys for years about respect and equity, since the twins were eleven and Cody was six (and not meant to be listening). She’d been determined to create young men who owned their emotions and articulated them. Men who had friendships with men and women. Men who didn’t touch anyone else’s body parts without clear permission. Long before #MeToo, Liv and the twins had talked about sex and consent, condoms and pregnancy, nudes and dick pics. Often reluctantly and squirming . . . but she’d done it. Liv had talked with the twins and Cody about the number of female characters in the board games they’d played and movies they watched. They’d talked about how the women in music videos wore far less than the men – who were often noticeably plain-looking, pudgy and covered up. Liv was trying to make her sons critical thinkers. Responsible humans. But, somehow, had her son become that boy? Jai, one of their reliable, sensible twins, who’d been nothing but compliant his entire life.

Jai returned to his phone.

‘Jai!’

‘Bedtime,’ Duncan said, flicking off the final light switch.

Wisely, Oscar made for the shower. When Jai looked up, Liv was disconcerted by the intensity of his gaze. It wasn’t malicious or angry. But it was unfamiliar. Like looking through a hole in the wall and finding an eye staring back at you.

‘Chill, Mum,’ he said. ‘It’s not a big deal.’

Tipping Anna George

An Instagram scandal at a grammar school sparks outrage in a bayside suburb and confronts the families involved. It might also be the catalyst for welcome change at the school and its community.

Buy now