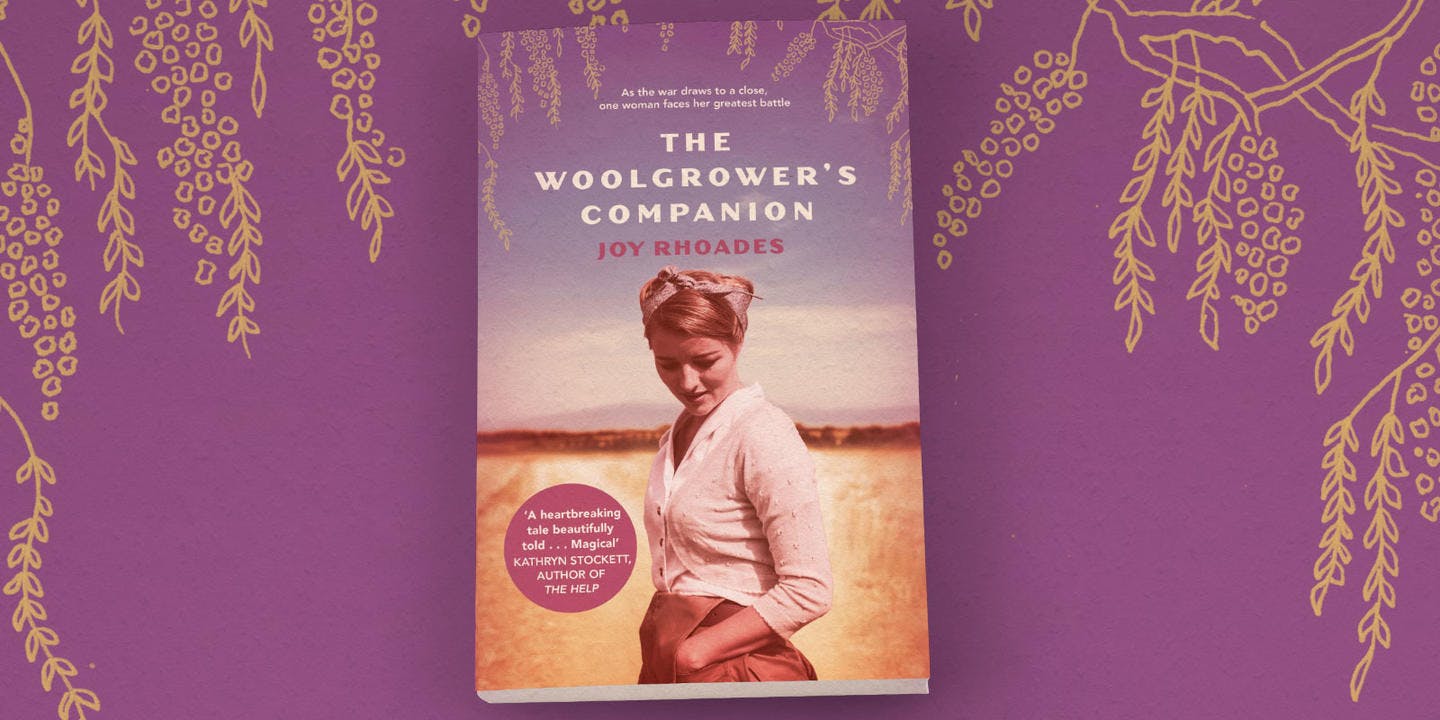

Joy Rhoades on the research behind The Woolgrower’s Companion.

The story that would become The Woolgrower’s Companion started not where it is set, on a remote Australian sheep property, but on the other side of the world in New York City. I was living in New York, and loving its noisy energy: taxi horns and buskers, garbage trucks and shouting. But when I sat down to write, what came into my head and what came out on the page, was the bush, the Australian bush of my childhood.

Growing up, I often heard family stories from my grandmother. She was a fifth generation grazier and had lived almost all of her life on her family’s sheep place in northern NSW, including through WWII. She was a wonderful storyteller and she loved the land. She’d speak of people, of droughts, and the occasional flood, of bushfires and snakes, of her love of birds and wallabies.

And in New York as I began to write, I found a story emerging, not my grandmother’s story but one inspired by her. Set in the Australian bush, it would be about a young woman, struggling to save her family’s sheep farm during the drought that lasted throughout WWII.

I wanted the story to be one that could well have happened. And while I had grown up in the bush, in a small town in western Queensland, I knew much less about sheep, grazing and the history of the war. I sought guidance from graziers, and other sheep experts, along with veterinarian and medical advice, and input from family and from friends. And I started to read the history. I contacted historians, seeking out academics who were experts in their particular fields, whether on soldier settlers, the military history of WWII, Italian POWs, the Stolen Generations and domestic servitude, or the wartime Red Cross, to talk through the relevant pieces of my story. I’d ask: does this hold up? I stand in awe of these wonderful historians, of their careful research and analysis, and their generous willingness to help make the story sound.

The area where I learned the most is the history of Aboriginal people. The more I read, the more I was ashamed at how little I knew. So I read and read, all sorts of wonderful books, like Donna Meehan’s It Is No Secret: The Story of a Stolen Child, Victoria Haskins’ One Bright Spot, Quentin Beresford’s Rob Riley story, and Rodney Harrison’s Shared Landscapes. I spent time on the Stolen Generations website, listening to testimony after testimony. It was heart-rending. Slowly a vision, sometimes terrible, of this part of history began to come into focus for me.

It was essential that I speak with and listen to the people of the land that I was writing about. I worked to be ready, prepared before I did so, to show my respect. I am so grateful and I salute the people who spoke to me or guided me. First among them are Catherine Faulkner, a woman of the Anaiwan Nation, who provided expert guidance on birthing practices, and help in ensuring respect for traditional knowledge and cultural practices; and activist and poet Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert, a woman of the Wiradjuri Nation – her keen eye on my manuscript and her gentle suggestions have taught me more than I could ever imagine.

I am grateful for what I learned during the writing of The Woolgrower’s Companion, about so many different things, and researching this book has changed the way I see things. I very much hope that that learning is a quiet presence in the book, an artery that carries a story of resilience and hope.