- Published: 17 March 2020

- ISBN: 9781760893606

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 288

- RRP: $24.99

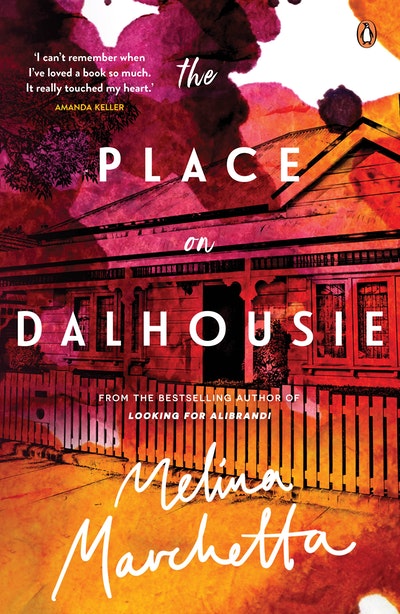

The Place on Dalhousie

Extract

‘Jim,’ he says.

Crazy eyes. A lunatic. Always the lunatics.

‘Rosie.’

‘For Rosemary?’

‘Rosanna.’

There’s a whole lot of shoving around them. On any given night The Royal gets half a dozen patrons, mostly old-timers. But tonight it’s packed, and no one wants to leave because Maeve from the newsagency’s brought along sandwiches and sausage rolls.

SES Jesus’s stare is intense. ‘You’re pretty.’

Rosie wants to hear something more original than that, but she lets him buy her a beer. What else is there to do but hear stories about the last big flood, of ’74, from some of the old blokes who haven’t spoken about anything interesting since?

And that’s all it takes. A couple of drinks and she’s back in some strange guy’s room, upstairs at the pub. His calloused fingers find their way between her legs and she realises that she’s going to spend another night of her life screwing a guy she doesn’t know. Makes her feel as if she can’t climb out of the bat cave, and the bleakness is smothering.

‘You’re going to have to stop doing that,’ she hears him say, and Rosie realises that she’s crying. He mutters something, but she doesn’t catch what it is.

Prickteaser? Bitch? Luke had an arsenal when it came to name-calling.

The guy on top of her – Jim, she remembers – falls back beside her. She can hear his ragged breathing. Wonders how much time she’ll let pass before she climbs out of his bed. The walls are paper-thin and she can hear the muffled sounds of two people having it off next door. She makes her move.

‘Stay,’ he says. It’s with a sigh. One of empathy, and she hasn’t felt anything close to that for a long time. She turns to face him in the dark, feels the tickle of his beard every time he takes a breath.

The lovers next door are at it. Rosie already knows their names because Stace needs to articulate in the third person everything she wants Roger to do to her.

‘Go to sleep,’ Jim murmurs.

‘While that’s going on?’

‘It’ll be over in less than a minute. Tops. I’ve listened to this four nights in a row. Roger takes about ten seconds to come.’

A moment later there’s silence from next door.

‘Told ya.’

Rosie chuckles and he laughs. A warm sound.

He’s gone when she wakes in the morning and she’s relieved they don’t have to do the polite stuff. Outside, it’s drizzling and steamy and her tee-shirt’s pasted onto her with the grime that comes from humidity and sweat. A couple of utes and four-wheel drives pass by, packed with possessions being taken to higher ground. Rosie wonders if she’s left it too late to get out of this town. Wishes Luke was here. Realises she hasn’t missed him at all, but he would have been someone to make a decision with. She’s been in this town for five weeks now. According to the Tidy Towns sign out on the highway, there are 970 people living here: all whingers, in her eyes. Those she’s met, anyway. Rosie hasn’t made a friend the whole time so she has no idea what to do when a flood is on the forecast except for what she heard last night from SES Jesus.

At the cenotaph one of the RSL guys is removing the wreaths, probably as a precaution. She’s never been into the whole Anzac thing so it surprises her that she’s memorised the twenty-six men who have died in wars since 1914. The names that stick out the most are the O’Hallorans. They make up eighteen of the dead and she wonders how many of them are left. She’s the last Gennaro of her family and the second last on her mother’s side. When Rosie and her Nonna Eugenia die, there’ll be none of them left. So much for big Italian families.

She crosses the low-lying bridge that takes her over the river and out to the old Simpson Road that backs onto the gully. There are half a dozen properties out here. It’s where she’s been living since Luke did a runner last week. When they first arrived in town, she found a job looking after someone who’d just had a hip replacement. Rosie hasn’t got any qualifications, but she does the housework, feeds the chooks, cooks and buys the old woman beer. There’s no love lost between her and Joy Fricker, but Luke’s departing gift was also nicking off with the money she had saved, so if Rosie wants to get out of this town sometime soon she doesn’t have much choice.

On the Fricker property she can feel the dampness on the grass. It’s too much water to have come from the morning drizzle, so she wonders if it’s already an overflow from the river. The house is an old two-storey Queenslander on stumps about seventy centimetres above the ground, so Rosie’s hoping it’ll keep them dry.

‘Still in the same clothes from yesterday.’

The ironically named Joy is sitting on the verandah. She wears eighty years of bitterness in a lower lip that hangs down in a constant bag of sourness.

Rosie ignores her and walks into the kitchen to fix breakfast. She whistles for Bruno, but there’s no bark of acknowledgement.

‘Where’s my dog?’ she calls out.

Miss Fricker’s followed her inside.

‘Made a nuisance of himself so I had to tie him up, didn’t I?’

Rosie bristles, but holds her tongue. Wants to tell the old woman that if she’s strong enough to tie up a kelpie border-collie cross then she can clean up after herself.

They eat in silence before she goes to run Miss Fricker’s bath, but nothing comes out. Last night, the head of emergency services was worried the lines would go underwater so she figures they’ve cut the power. Most properties have a generator that kicks in, but no one’s looked in on Miss Fricker since Rosie arrived, so she can’t imagine a flood plan’s in place.

She spends the morning with SES Jesus’s instructions in her head, because he was a talker and didn’t shut up the whole night. Removes anything she can off the floor in the living room and kitchen. The cane armchairs, the rug, baskets and vases. The furniture she’s able to lift, she piles onto the table. In the kitchen, she grabs some of the china that looks sentimental and packs it away in a box with the photos on the mantelpiece before taking it all upstairs into the spare bedroom. Miss Fricker watches the whole time, her eyes suspicious. Once or twice Rosie hears Bruno barking and peers outside, but it’s not until early afternoon that she’s alarmed to see water almost up to the chicken coop, about ten metres from the back steps of the house.

‘We need to get to the evacuation centre in town,’ she tells Miss Fricker.

‘I’m not going anywhere.’

‘We can’t stay here, Joy. We could be cut off for days.’

‘This is just a way of getting me out of my house and sticking me in that nursing home!’

It’s all Rosie’s heard for weeks, because Joy Fricker’s nephews are pricks, dying to get their hands on the property to sell. The problem for the Fricker boys is that their aunt still has her wits and isn’t going to sign anything over to them. But Rosie doesn’t give a shit about the Fricker family problems and she’s not staying if the banks of the Dawson have broken. Once she’s retrieved Bruno, she’s out of here.

Outside, in knee-deep water, she heads to the yard where Miss Fricker’s gone and tied Bruno a couple of metres away from the goat. She’s thrown by how fast the water’s risen. SES Jesus had warned her that when it came, it was full-on. He had seen it down south when he was living in Lismore. He was a city boy, amazed by how everything could change in less than five minutes. It takes Rosie more than one attempt to undo the goat and the moment he’s free, he nicks off. Rosie wades over to where Bruno is barking. The water suddenly hurls her forward, slamming her into the fence, winding her. It’s only Bruno’s whine that has her struggling to her feet to clutch the post and edge towards him, the splinters digging deep into her palm until she feels the wet fur of his coat against her arm. She’s frightened to untie him for fear of him being swept away, but can’t bear the idea of keeping him tethered in case he goes under and drowns in front of her. Because if he does, Rosie knows she’ll let go. Fears she’s been wanting to let go for so long now.

Studying the flow around her, she takes a chance. Carefully unties Bruno and wraps the leash around her wrist, but goes under twice and feels herself being swept away. It’s only the Hills hoist that she latches herself onto that stops them. She’s colder than she’s ever been in her life but she doesn’t move because the water has a rage beyond anything she’s seen, and it wants to snatch them both, wants to fling them against a tree trunk or the side of the house. There’s a vengeance to its force and she can’t fight it because she’s bone-tired. Wants to close her eyes, except Bruno is growling beside her and she knows they have to find their way back up those steps. But as cold and frightened as she is, Rosie feels safe staying put. Because in the backyard of the house in Dalhousie Street, her best memories were of the Hills hoist. Of her mother singing Rosie songs in dialect. Rosie knew them all and she sings them quietly in Bruno’s ear until it’s her mother’s voice she can hear. Clearer than she has for years.

She doesn’t know how long they stay. Doesn’t know how she finds the strength to let go again, but somehow they make it inside. The entire downstairs is flooded and for an awful moment she thinks Joy Fricker has been swept away. Until she sees the old woman sitting waist-deep in water on the stairs, her teeth chattering.

‘Upstairs,’ Rosie manages to say. Miss Fricker shakes her head and Rosie figures that she’s tried to get up those stairs and failed. For once, she feels sorry for her. There’s a vulnerability that Rosie hasn’t seen before, even after the hip replacement when she couldn’t wipe her bum without help.

‘We can’t stay down here, Joy. Let’s go.’

Rosie’s no bigger than Miss Fricker and she buckles under her weight as she helps her step by step, Bruno at their heels shoving them forward. She’s worried that she’ll snap Miss Fricker’s arm, but better a broken arm than being found facedown in rancid water.

In the musty-smelling room that Joy Fricker hasn’t used since her operation, Rosie removes the old woman’s wet clothing and dresses her. In her own room, she strips off and finds a pair of shorts and a tee-shirt, anything that won’t drag her down if she ends up back in the water. The deluge becomes a phantom in her head, and she imagines it creeping its way up, engulfing them, so she drags a chair onto the landing and keeps watch at the top of the stairs. Has no idea what she’ll do if that water slinks towards them, but needs to know what she’s up against.

Later, in the dark, she feels a shudder of the house, picks up the torch and goes to the window, trying to get a glimpse of whatever’s coming downstream to hammer them.

‘My father built this house for me.’

Rosie jumps at the sound of her voice, shines the light towards Miss Fricker, who’s standing at her bedroom door.

‘It’s got good foundations.’

Rosie helps the old woman back into bed and then curls up in the tacky velvet armchair close by. On the wall, the Sacred Heart of Mary clock taunts her, moving at the excruciating speed that punishes those who are praying for time to pass.

‘If my father knew what his grandsons were trying to do, it would have broken his heart,’ Miss Fricker says. For her, there still seems to be a greater malevolence than a flood.

Despite the darkness, Rosie can feel the old woman’s bitter scrutiny.

‘You look the type to break your father’s heart.’

‘Yeah, but he broke mine first.’

A voice wakes them. Bruno is barking at the bedroom door and Rosie untangles herself from the chair, blinded by daylight that snuck up on her while she wasn’t looking. She wipes saliva from her mouth and heads to the landing.

‘Looters,’ Miss Fricker whispers from her bed, because everyone is the enemy in her eyes. Rosie puts a finger to her lips and creeps down a step for a look. SES Jesus is standing thigh-deep in water, wearing only his budgie smugglers and orange SES jacket. Not quite an apparition, but Rosie feels a hysterical laugh bubble up inside her at the sight of him.

‘Told you to get to higher ground,’ he says.

‘Have you got a boat?’

He shakes his head. ‘The CFA have lent us their truck. Outboard motors are too dangerous. Who knows what’s under this water.’

Rosie helps Miss Fricker out of bed and can feel the old woman trembling. On the mantelpiece, she sees a Mary MacKillop brooch and pins it onto Miss Fricker’s dress before walking her to the door. The old woman refuses to take another step at the sight of him coming up the stairs.

‘Now they’re hiring perverts,’ she mutters.

‘You’re going to have to put your arms around my neck,’ Jim tells Miss Fricker, ‘and I’m going to have one arm around your back and the other under your knees.’

And there’s something about the way skinny SES Jesus hitches Miss Fricker up in his arms and wades through the deluge that makes Rosie think that she’d follow him anywhere.

It’s the town butcher who drives the CFA truck through the floodwater. He loses control of the wheel more than once, yelling Christ at the top of his lungs. Rosie feels the perspiration running down her brow, undoes her seatbelt, readying herself for the inevitable. They’ll go under, for sure, trapped in a tomb of water. As if sensing her fear, Jim turns in the front seat, catches her eye.

‘Almost there, mate.’

They pass the cenotaph and Rosie sees shops half submerged, garbage bins bobbing in filthy brown water and an elderly couple sitting on the roof of their car being towed by a ute. The butcher, Mick, she thinks, swears at a couple of kids watching it all, sitting on the awning above the fish and chips shop, laughing their heads off, oblivious to the fear. And it’s only SES Jesus’s calm instructions to Mick, suggesting another route down less dangerous roads, that brings Rosie any comfort.

The evacuation centre is in the cottage owned by the Country Women’s Association, perched high on a hill. Standing at the entrance Rosie sees a familiar face, one she’s locked horns with before. A couple of weeks back she had to pick up medication for Miss Fricker at the hospital pharmacy and was put through the third degree by this woman, a local midwife who had come in to deliver a baby. This morning she looks at Rosie with just as much hostility.

‘No dogs allowed, love,’ she says.

Rosie can’t believe what she’s hearing. ‘I’m not leaving him outside.’

‘I’ll take him someplace safe,’ Jim says.

But Rosie’s shaking her head. ‘I’ll keep him in a corner and he won’t move.’

The midwife holds up a finger of warning at Rosie. ‘No dogs allowed,’ she repeats before leading Miss Fricker away. Rosie feels tears threatening, but she refuses to cry in front of Jim for a second time. The butcher’s honking the horn and Jim holds out a hand to her. She lets him take the leash and he walks away.

Inside the cottage there are three large living spaces, all packed with people, most sleeping on solid-looking mattresses. Rosie notices a couple of the older evacuees are lying on comfy armchairs. She checks on Miss Fricker before searching out the midwife who she finds in the CWA kitchen, boiling water on a portable stove.

‘We need one of those armchairs,’ Rosie says.

‘Be patient,’ the other woman says without looking up. ‘Everyone’s gone through a lot, okay. You’re not the only one.’

‘Miss Fricker’s had a hip replacement,’ Rosie insists. ‘She needs to be comfortable.’

‘Sorry, love, none left for the time being.’

‘Don’t fucking “sorry love” me again,’ Rosie says.

The midwife looks up. Rosie flinches because the woman reminds her too much of her mum. They would have been the same age, both with long black wavy hair and fierce dark eyes, except the midwife’s an Islander. And the owner of the mothership of dirty looks.

‘You need to change your attitude.’

‘I’ll change it when you get Miss Fricker onto something comfortable.’

Soon after, two teenagers carry an armchair to where Miss Fricker is sitting on a fold-up seat beside Maeve from the newsagency, who hasn’t stopped speaking since they arrived. Rosie’s heard Miss Fricker say, ‘Shut up, Maeve,’ more than once.

‘Aunty Min says it’s from the office so you better take care of it,’ the older of the boys says.

Later, Rosie finds Min the midwife watching them from the door. Regrets not looking away before she’s beckoned over by an aggressive hand.

‘What?’ Rosie says.

Another scathing look. ‘Don’t you “what” me, you little bitch. Come and help me with morning tea.’

Handing out tea and biscuits means that people want to talk. Most are worried about their homes. Their pets. Their photos. Their insurance documents. Maeve is in tears.

‘Everything in the shop’s gone,’ she tells Rosie. ‘Everything. What if they won’t cover me?’

Rosie’s grateful that she has nothing to lose.

‘It could be worse, Maeve,’ a woman with a couple of kids hanging off her says from across the room. One of her girls has been crying for their dog all morning because they had to leave him behind.

Later that day, it does get worse. SES Kev and a couple of young guys come in, looking gutted. After that, it’s like the power company’s come in and turned off everyone’s voices. Because down by one of the properties backing onto the river, a baby’s been swept from his father’s arms, and out by the old mill road, two people are missing. Their car went over the embankment.

Min hands Rosie a folder. Tells her to tick off the names from the electoral roll. They need to start working out where everyone is. Most have gone to family and friends on higher ground. Some stayed in their homes and have ended up here. Rosie can’t help thinking that she’s not on the town electoral roll. If she’d got swept away from the Hills hoist yesterday, she wouldn’t have even been considered missing.

Jim comes looking for her later and they just stand around for a while until he says, ‘You want to go somewhere?’

And in his room upstairs at the pub, her legs are wrapped around his hips and there isn’t really that much time for pleasantries or catch-up, but she doesn’t care; for most of it, she’s in her world and he’s in his and it’s fast and she likes the fact that she doesn’t have to pretend with this guy.

Later, she asks where he’s from.

‘Sydney. You?’

She can’t believe it. ‘Same.’

No more questions, she tells herself.

But can’t resist.

‘Where?’

‘Grew up in Waterloo but mainly hang out in the inner west when I’m home. Close to you?’

Closer than she’d care to admit. She doesn’t answer. Rosie doesn’t want to think of Dalhousie Street and who lives there now.

‘What are the chances?’ he says. ‘You and me from the same place.’

Rosie’s dad believed in chances and fate. He believed in signs. Rosie doesn’t believe in anything hopeful.

‘What’s your story?’ he asks.

She shrugs. ‘No story.’ Because exchanging misery isn’t her style, and at the moment even her misery can’t top a baby being swept away.

They talk about Bruno.

‘He’s out on a property off the highway,’ Jim tells her. ‘You know, near the goods-train track. The family’s looking after a few other animals. I don’t think he likes goats.’

He glances at her.

‘History of goat trouble in his past?’

She laughs for the second time in days.

The Place on Dalhousie Melina Marchetta

From the bestselling author of Looking for Alibrandi comes this perfectly crafted novel about families, relationships and the true nature of belonging.

Buy now