- Published: 30 August 2022

- ISBN: 9781760899936

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $32.99

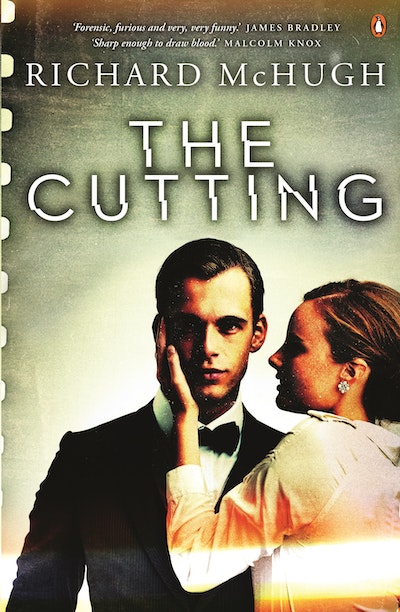

The Cutting

Extract

Will was sitting in the back row of a large dining hall-cum-auditorium in the middle of nowhere. A sea of men in hi-vis gear was lapping against the walls. Something bad was about to happen to them, and to Will, and either they didn’t realise it, or they were too piss-weak to protest. Whichever it was, Will felt his co-workers at Madeleine’s Monster, the world’s freshest iron ore mine, were letting him down.

A man – Justine’s mate, her philanthropist, her benefactor, of all people – was standing on a small stage down the front speaking into a microphone. Around forty, well-dressed, well-groomed, well-tanned, handsome and charismatic – and gesturing hammily with his free arm – he spoke with an irksome, lulling, chocolaty mid-Pacific twang in that American presidential shop-floor style. And they were all buying it. Will glanced around the room, trying not to meet anyone’s eye. He needn’t have worried. All were spellbound to the man with the microphone.

The building they were in was barely nine months old. Will had been part of the team that supervised its erection by a multinational construction giant. They had fitted it out with the soul of a casino: 6.30 am might have been midnight or midday. Outside, he knew, the silent white sun was pinning up a cobalt sky, etching hard shadows in the bloodshot-orange Pilbara earth. Inside, hundreds of strip lights were humming their fluorescent song of hospital green: 50Hz of nowhere to hide. This shadowless space was new but already it stank of curing glue and walked-in diesel, of scrambled eggs and red dust and sweat, of . . . One of the bogans had farted.

The man’s soothing phrases – my grandmother’s legacy and Madeleine’s vision and future prosperity and together and development and share in the wealth of the north-west – had been hovering airily, imperfectly, over Will’s consciousness. Now, in the fart-stench, they resolved themselves into the clamouring, unalterable, terrible present, the present of How am I going to tell my mother? And What can I possibly say to Justine? His girlfriend should have been a dependable source of sympathy at a time like this. But the roiling in his guts said otherwise. After all the bickering lately, he’d started to wonder whether they’d lost their way. He felt the floor falling away beneath him.

For the little piece of theatre that was playing itself out at dawn on the stage in that malodorous space, the thing from which Will had so wished to disconnect himself, was the liquidation of an entire workforce. The man with the microphone was Lance Alcocke, the Executive Chairman of APC Minerals. This megalomaniacal narcissist, champion of incarcerated children everywhere, social entrepreneur and sole heir to one of the country’s great fortunes, was telling Will and his twelve hundred colleagues a story that was going to end with them all unemployed.

In fairness – a fairness Will begrudged him – the Chairman had come a very long way to say all this. He could have instructed an underling to send everyone simultaneous text messages, a now standard means of binning miners. But no. He’d flown overnight (by private jet) all the way from Sydney as soon as the negotiations with his backers collapsed so he could front his employees before they read about the company’s disintegration on social media. Which you’d think would be to his credit. But somehow, despite the calamity his failure of corporate stewardship represented for the workers, he was managing to make it all about himself.

It was plain to Will that none of the people in that room mattered to Lance Alcocke. All that mattered was his self-regard. A gaping neediness had brought him here: a compulsion to justify himself, to explain how it was that the company he directed had lost control of its business through no fault of his. This narrative of personal victimhood had a fine cast of villains: Chinese buyers; Korean backers; the company’s rivals at Rio and BHP and Vale. He could have blamed an asteroid falling from the sky for all Will cared.

Finally, the Chairman spelled it out for anyone with their head still in the sand: their jobs had ceased to exist. He was doing his best to persuade them it was all unavoidable. The logic was impeccable, if you accepted his premise: that the money had run out. Will seemed to be the only one who’d noticed a basic problem here. Lance Alcocke was born rich, and he was going to stay rich. Although he’d always seemed normal enough when he met them in groups of five or ten in the workshops or out at the pit, standing on that stage today he was as remote as the Emperor of Japan. He would not share their fate. Whatever happened to his mine, whatever happened to his company, he would be the same tomorrow as he was today: a rich guy. The man was a kind of celebrity, a playboy, a darling of the social pages, and – most paradoxical of all – a moneyed hero to Justine and her mates. That last part was enough to make a young engineer like Will vomit.

But here in the Pilbara, where a human Krakatoa of loss and grief and fear should have been rising from the deep bogan sea, where the same angry thought should have been forming in twelve hundred hostile minds, that the Bali villa weekends, the hotted-up utes, the women, the men, the booze, the drugs, were all over, there was silence. They owed this fucker nothing, Will thought with disgust, and still the guy had their sympathies. He was charming, and he could talk the talk, and it all sounded like it was coming from the heart, but that couldn’t explain the dull acquiescence with which his audience was downing their Kool-Aid. Will figured it had to be mass shock.

He’d now exhausted the distracting power of his disenchantment with others. He had just enough time to congratulate himself on this insight before a giant pink teddy bear of self-pity plonked itself down on his lap to remind him of what really mattered. He threw his arms around it and made himself one with its plush polyester wretchedness. Will was twenty-five. He hated engineering. He hated being filthy. He was about to lose his income. His artsy lefty girlfriend Justine J’accuse! Jamison had been making noises about getting married or leaving him, or possibly both. And his destiny appeared to be on a collision course with the couch in his mother’s flat in Fairfield.

Comparing himself with his contemporaries wasn’t helping. His schoolmates back in Sydney worked in clean, white-collar jobs in air-conditioned office towers with occasional glimpses of the Harbour – water cameos, the real estate agents called them. They had money; they had normal five-or-six-day weeks and two-or-one-day weekends; they were negatively-gearing Sydney real estate. From what he understood, the ones with (non-accusing) girlfriends were happy enough and the ones without were even happier. No one would understand his plight. How could they?

The solution to the crisis presented itself in the way that, for Will, it generally did these days. He needed a distraction. He needed a hit. But – purely recreational user that Will was – he’d always had the sense not to bring drugs to a mine site. There were just too many things that could go wrong, not to mention the random testing. Alcohol would have given him a socially acceptable holding pattern until he could land his shot-up plane on something more obliterating, but Maddie’s Bar wasn’t open at 6.45 am and they were forbidden to have anything – even beer – in their rooms, on pain of immediate termination. The irony of which smacked him in the forehead, an irritant further corroding his view of the world and himself. Feeling defeated, he realised there was only one course left to him: a major porn binge.

There was no reason to sit through any more of Alcocke’s song-and-dance routine. The financial details of their redundancy packages would be set down in writing and emailed and haggled over. His workmates would tell him all about it later.

This last thought caused Will a pinprick of further unhappiness, of disappointment in himself for not having spared them a thought sooner, tinged with an actual concern for their well-being. Tran and Vish, the two guys he most liked in the whole outfit, worked in IT in the control centre at head office on the outskirts of Perth. It was cheaper to keep people there at the other end of a fibre-optic cable, not having to pay to FIFO them in and out of the Pilbara.

Will wondered if they knew what was going on. Of course they did. They monitored the company’s systems in real time and knew everything before anyone else. They’d probably have jobs with APC for a month or two more at least, maybe longer. The wind-down, the mothballing, the sacking; it all needed IT. The computers were kept on life support longer than the people these days. And after that, with their skill sets, they’d find other jobs. Tran might even take a holiday. Vish couldn’t hang about, wouldn’t wait to get a new job: Will was sure he had mouths to feed back home.

He stood and started making his way along the row. The honeyed flow of words from the stage hiccoughed. He felt Alcocke’s eyes on his back – he was making a show of stopping to take note of this first rat abandoning ship. Will didn’t turn around. He knocked his shins on knee after unmoving knee and headed for the exit. Whatever else fate might have in store for him today, he was sure of this much: he wasn’t going to turn up to work. What were they going to do? Sack him?

No, he was going to plug himself, as directly as he humanly could via the screen on the wall opposite his bed and his earphones, into the glorious, unfettered aggregation of possibility that was the internet. He’d discovered in the last few months he had a thing for MILFs: Mothers He’d Like to Fuck. He wasn’t sure why this genre held such a spell over him, and he didn’t want to know. Although his girlfriend was herself three years his senior, older women did seem to take his mind off Justine. And he had had about as much as he could cope with of longing for her absent body, of his guilt for wanting someone else and indulging that want with the scabbiness of porn and, lately, of the fear of losing her.

The Cutting Richard McHugh

A darkly humorous novel about modern Australia and what it means to be a good person.

Buy now