- Published: 3 September 2018

- ISBN: 9781405930956

- Imprint: Michael Joseph

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 368

- RRP: $24.99

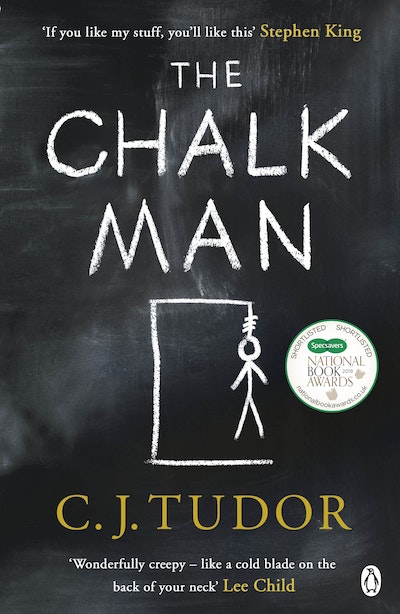

The Chalk Man

The chilling and spine-tingling Sunday Times bestseller

Extract

They knelt down beside the unseeing girl. Their hands gently caressed her hair and stroked her cold cheek, fingers trembling with anticipation. Then they lifted up her head, dusted off a few leaves that clung to the ragged edges of her neck, and placed it carefully in a bag, where it nestled among a few broken stubs of chalk.

After a moment’s consideration, they reached in and closed her eyes. Then they zipped the bag shut, stood up and carried it away.

Some hours later, police officers and the forensic team arrived. They numbered, photographed, examined and eventually took the girl’s body to the morgue, where it lay for several weeks, as if awaiting completion.

It never came. There were extensive searches, questions and appeals but, despite the best efforts of all the detectives and all the town’s men, her head was never found, and the girl in the woods was never put together again.

2016

Start at the beginning.

The problem was, none of us ever agreed on the exact beginning. Was it when Fat Gav got the bucket of chalks for his birthday? Was it when we started drawing the chalk figures or when they started to appear on their own? Was it the terrible accident? Or when they found the first body?

Any number of beginnings. Any of them, I guess, you could call the start. But really, I think it all began on the day of the fair. That’s the day I remember most. Because of Waltzer Girl, obviously, but also because it was the day that everything stopped being normal.

If our world was a snow globe, it was the day some casual god came along, shook it hard and set it back down again. Even when the foam and flakes had settled, things weren’t the way they were before. Not exactly. They might have looked the same through the glass but, on the inside, everything was different.

That was also the day I first met Mr Halloran, so, as beginnings go, I suppose it’s as good as any.

1986

‘Going to be a storm today, Eddie.’

My dad was fond of forecasting the weather in a deep, authoritative voice, like the people on the telly. He always said it with absolute certainty, even though he was usually wrong.

I glanced out of the window at the perfect blue sky, so bright blue you had to squint a little to look at it.

‘Doesn’t look like there’ll be a storm, Dad,’ I said through a mouthful of cheese sandwich.

‘That’s because there isn’t going to be one,’ Mum said, having entered the kitchen suddenly and silently, like some kind of ninja warrior. ‘The BBC says it’s going to be hot and sunny all weekend . . . and don’t speak with your mouth full, Eddie,’ she added.

‘Hmmmm,’ Dad said, which was what he always said when he disagreed with Mum but didn’t dare say she was wrong.

No one dared disagree with Mum. Mum was ‒ and actually still is ‒ kind of scary. She was tall, with short dark hair, and brown eyes that could bubble with fun or blaze almost black when she was angry (and, a bit like the Incredible Hulk, you didn’t want to make her angry).

Mum was a doctor, but not a normal doctor who sewed on people’s legs and gave you injections for stuff. Dad once told me she ‘helped women who were in trouble’. He didn’t say what kind of trouble, but I supposed it had to be pretty bad if you needed a doctor.

Dad worked, too, but from home. He was a writer for magazines and newspapers. Not all of the time. Sometimes he would moan that no one wanted to give him any work or say, with a bitter laugh, ‘Just not my audience this month, Eddie.’

As a kid, it didn’t feel like he had a ‘proper job’. Not for a dad. A dad should wear a suit and tie and go off to work in the mornings and come home in the evenings for tea. My dad went to work in the spare room and sat at a computer in his pyjamas and a T‑shirt, sometimes without even brushing his hair.

My dad didn’t look much like other dads either. He had a big, bushy beard and long hair he tied back in a ponytail. He wore cut-off jeans with holes in, even in winter, and faded T‑shirts with the names of ancient bands on, like Led Zeppelin and The Who. Sometimes he wore sandals, too.

Fat Gav said my dad was a ‘frigging hippie’. He was probably right. But back then, I took it as an insult, and I pushed him and he body-slammed me, and I staggered off home with some new bruises and a bloody nose.

We made up later, of course. Fat Gav could be a right penis-head ‒ he was one of those fat kids who always have to be the loudest and most obnoxious, so as to put off the real bullies ‒ but he was also one of my best friends and the most loyal and generous person I knew.

‘You look after your friends, Eddie Munster,’ he once said to me solemnly. ‘Friends are everything.’

Eddie Munster was my nickname. That was because my surname was Adams, like in The Addams Family. Of course, the kid in The Addams Family was called Pugsley, and Eddie Munster was out of The Munsters, but it made sense at the time and, in the way that nicknames do, it stuck.

Eddie Munster, Fat Gav, Metal Mickey (on account of the huge braces on his teeth), Hoppo (David Hopkins) and Nicky. That was our gang. Nicky didn’t have a nickname because she was a girl, even though she tried her best to pretend she wasn’t. She swore like a boy, climbed trees like a boy and could fight almost as well as most boys. But she still looked like a girl. A really pretty girl, with long red hair and pale skin, sprinkled with lots of tiny brown freckles. Not that I had really noticed or anything.

We were all due to meet up that Saturday. We met most Saturdays and went round to each other’s houses, or to the playground, or sometimes the woods. This Saturday was special, though, because of the fair. It came every year and set up on the park, near the river. This year was the first year we were being allowed to go on our own, without an adult to supervise.

We’d been looking forward to it for weeks, ever since the posters went up around town. There were going to be Dodgems and a Meteorite and a Pirate Ship and an Orbiter. It looked ace.

‘So,’ I said, finishing my cheese sandwich as quickly as I could, ‘I said I’d meet the others outside the park at two?’

‘Well, stick to the main roads walking down there,’ Mum said. ‘Don’t go taking any shortcuts or talking to anybody you don’t know.’

‘I won’t.’

I slid from my seat and headed to the door.

‘And take your bumbag.’

‘Oh, Muuuuum.’

‘You’ll be going on rides. Your wallet could fall out of your pocket. Bumbag. No arguments.’

I opened my mouth and shut it again. I could feel my cheeks burning. I hated the stupid bumbag. Fat tourists wore bumbags. It would not look cool in front of everyone, especially Nicky. But when Mum was like this, there really was no arguing.

‘Fine.’

It wasn’t, but I could see the kitchen clock edging closer towards two and I needed to get going. I ran up the stairs, grabbed the stupid bumbag and put my money inside. A whole £5. A fortune. Then I charged back down again.

‘See you later.’

‘Have fun.’

There was no doubt in my mind I would. The sun was shining. I had on my favourite T‑shirt and my Converse. I could already hear the faint thump, thump of the fairground music, and smell the burgers and candyfloss. Today was going to be perfect.

The Chalk Man C. J. Tudor

Children aren't always so innocent in this Stephen King-style thriller, backed by MJ's biggest marketing campaign for a debut this year

Buy now