- Published: 5 January 2021

- ISBN: 9781761042089

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 400

- RRP: $22.99

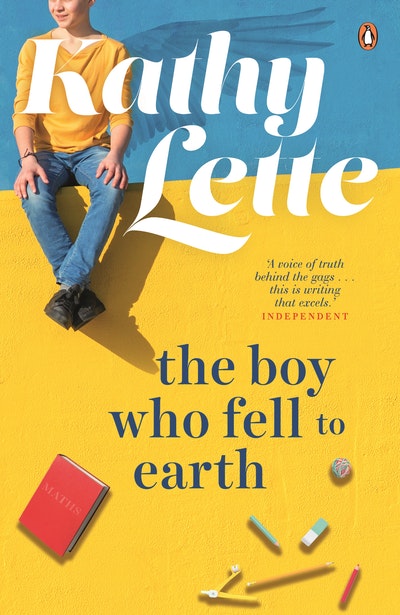

The Boy Who Fell to Earth

Extract

Prologue

The car hits my sixteen-year-old son at 35 miles per hour. His body jack-knifes skywards then falls with a sickening thud on to its bonnet before bouncing down to the bitumen. The last words I’ve said to him just two minutes earlier are ‘You’ve ruined my life. I wish I’d never had you. Why can’t you be normal?!’

I’d tried to claw back these words as we faced each other in the kitchen but they rained down upon my child like blows. He’d stood, silent as a monument for a moment – then he was gone in a wild blur of limbs.

As I heard the door slam, I sat there aghast, helpless, horrified. I then gave chase, calling his name. I could see the pale denim of his legs scissoring towards the busy road. I heard the low rumble of a car cresting the hill. I spasmed with fear and then the world crumpled.

The windscreen winced at the impact, then shattered. The smashing glass tinkles like waves on shingle. The wheels throw up dirt and noisy gravel as the driver brakes in a belch of petrol. The earth moves slowly up towards my son’s golden head. He collapses, like a crushed cigarette packet. I freeze in the tourniqueted silence. The pedestrians are so still they’re like a concert audience hushed in anticipation . . . Then terror detonates inside me. Each ragged breath feels as though I’m inhaling fire. I hear a primal, bloodcurdling scream and realize it’s my own.

I fall to my knees beside him. A thickening, lacquered pool of blood is forming on the road. And then the air is cleaved by my wailing. The world darkens and everything goes black.

I’m in the ambulance now. How much time has elapsed? I replay the impact, over and over. The smell of burning rubber. The full-throated roar of the crash. The terror exploding on to the screen of my eyelids. I feel again the shriek in my blood. The earth and sky merging, imploding, then finally coalescing into fact: my son has been hit by a car. My eyes start to burn and my body trembles. Grief shakes me between its jaws like a lion shakes a half-dead gazelle.

Intensive care. The doctor’s voice seems to shout, as if from far away: ‘Your son’s in a coma.’ And then I’m vomiting in the toilet, dousing my face with water over the sink and shaking myself dry like a wet animal.

So the vigil begins. I watch over my darling. His skin is the colour of a cold roast. I strain my eyes until they sting but see no movement. I stroke a bruise which is erupting with the speed of a Polaroid on his soft cheek. Where is Superman when I need him, to reverse the earth’s rotation so that I can go back in time and not utter those hateful words to my dear, dear boy? Where is Stephen Hawking’s wormhole in space, his gateways linking different parts of the universe so I can quantum-leap backwards and bite my tongue? I whisper into Merlin’s ear about how much I love him. Knowing how uncomfortable he is with emotion, I jokingly promise to eat my own foot so I won’t put it in my mouth ever again. All the time my tears splosh on to the sheet, and a great stalactite of snot hangs from my nose.

‘Is there anyone you want to call?’ a nurse asks, under the glare of naked electricity. ‘His father?’ she suggests, tentatively.

‘His father?’ After Merlin’s diagnosis, Jeremy retreated into work. I used to joke that it was a wonder British Airways hadn’t embroidered his monogram on a business-class seat as he was in the sky more than he was on the ground. The smell of antiseptic cuts pungently through the air. Outside, the night is seeping away, dwindling into dawn. Below the hospital window, I see the cars parked diagonally, like sardines nosing up to a tin can – cars belonging to workers who will soon be going home to happy lives and unhurt children.

The nurse places her hand on my arm and guides me down into a chair. She sits beside me. Still holding my arm and stroking my skin, she repeats in a gentle voice, ‘Is there anyone you’d like me to call, pet?’

‘This is all my fault.’ Raw with weeping, racked with guilt, my voice is seesawing with emotion.

‘I’m sure that’s not true. Why don’t you tell me all about it, love. But first, there must be somebody you’d like me to call?’

‘No. There’s only ever been Merlin and me.’ She takes my hand. ‘Tell me,’ she says.

Part One: Merlin

1

I’ve Just Given Birth to a Baby but I Don’t Think It’s Mine

Like many English teachers, I dreamt of being an author. All through my pregnancy I made cracks to Jeremy, my husband, about naming my firstborn ‘Pulitzer’ – ‘just so I can say I have one’. But I was sure about one thing. I wanted our son to have a name which would make him stand out in a crowd, something out of the ordinary to mark him as different . . . Well, not in my wildest imaginings could I have known how different my son would turn out to be.

My wunderkind started speaking early, then, at eight months, just stopped. No more cat, sat, hat, duck, truck . . . Just a perplexing, deafening silence. By the time he was one year old, his behaviour was repetitive, his moods fractious, his sleep erratic, his only comfort being plugged into my raw breast. I was worried I’d be breastfeeding him until he went to university.

Until I began to wonder if he ever would...

As Merlin was my first child, I wasn’t sure if his behaviour was abnormal and made tentative enquiries to relatives. Since my father’s fatal aneurism while in bed with a Polish masseuse (and part-time druid priestess), my mother had been mending her broken heart by spending his life insurance on a never-ending globetrot. Unable to reach her in the Guatemalan rainforest or halfway up Mount Kilimanjaro, I turned to my in-laws for advice.

Jeremy’s family enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle on the land, just outside Cheltenham – and before you start picturing the kind of family that has a wealthy lifestyle outside Cheltenham, let me assure you that you’re absolutely spot on. When I tried to broach the subject, my father-in-law’s eyebrows took the moral high ground. Jeremy’s father had achieved his life’s ambition of becoming a Tory MP, for Wiltshire North. He had a broad, severe forehead like Beethoven but was completely tone deaf to life’s lyricism. It’s quite a Newton-defying feat, really, to rise by gravity. But that’s what he’d done. The very earnest Derek Beaufort was the coldest, smoothest man I’d ever met. He was remote, chilly, self-absorbed; I’d often glimpse him on news programmes working hard at turning up the corners of his mouth into what could be mistaken for a smile. He didn’t even attempt to simulate friendliness now.

‘The only thing wrong with Merlin is his mother,’ he proclaimed.

I waited for my husband or my mother-in-law to leap to my defence. Jeremy squeezed my hand under the heavy mahogany heirloom dining table but kept wearing his expression of bolted-on politeness. Mrs Beaufort’s (think Barbara Cartland but with more make-up) smile thinned out between twin brackets of condemnation. She had always let me know that her son had married beneath himself. ‘Which is true, as I’m only five foot three,’ I’d joshed to Jeremy at our engagement party. ‘Just think, darling, you can use me as a decoration on our wedding cake.’

Merlin was two when the doctor made his diagnosis. Jeremy and I were sitting side by side in the paediatric wing of the London University College Hospital. ‘Lucy, Jeremy, do sit down.’ The paediatrician’s voice was light and falsely cheery – which was when I knew something was seriously wrong. The word ‘autism’ slid into me like the sharp, cold edge of a knife. Blood pulsed into my head.

‘Autism is a lifelong developmental disability which affects how a person relates to other people. It’s a disorder of neural development chiefly characterized by an inability to communicate effectively, plus in appropriate or obsessive behaviour . . .’ The paediatrician, kind but robust, his white hair floating above him like a cumulus cloud, kept talking, but all I heard were exclamations of protest. Rebuttals clattered through my cranium.

‘Merlin is not autistic,’ I told the doctor emphatically. ‘He’s loving. He’s bright. He’s my perfect, beautiful, adored baby boy.’

For the rest of the consultation, I felt I was buckling with pressure, as if I were trying to close a submarine hatch against the weight of the ocean. I glanced through the glass panel at my son in the waiting-room playpen. His tangled blond curls, ruby-red mouth and aquamarine eyes were so familiar. But this doctor was reducing him to a label. Suddenly Merlin was little more than an envelope with no address.

An ache of love squeezed up from my bone marrow and coagulated around my heart. Dust motes danced in the heavy air. The walls, a bilious yellow, looked how I felt.

‘He will have developmental delays,’ the doctor added parenthetically. This was a diagnosis which pulled you into the riptide and dragged you down into the dark.

‘You can’t be sure it’s autism,’ I rallied. ‘I mean, there could be some mistake. You don’t know Merlin. He’s more than that.’ My darling son had become a plant in a gloomy room and it was my job to pull him into the light. ‘Isn’t he, Jeremy?’

I swivelled towards my husband, who sat, rigid, in the orange bucket chair next to me, gripping the armrests as though trying to squeeze blood from them. Jeremy’s profile was so chiselled it belonged on a coin. He looked dignified but suffering, like a thoroughbred coming in last in a hacking event.

Falling in love with Jeremy Beaufort, I had scraped the top of the barrel. When I first saw him – tall, dark, turquoise-eyed and tousle-haired – if I’d been a dog I would have sat on my hindquarters and hung my tongue out. The first thing he told me when we met on the red-eye from New York – the flight had been a gift from my sister, an airline stewardess, for my twenty-second birthday – was that he loved my laugh. A few weeks later he was telling me on a daily basis how much he loved my ‘succulent quim’.

But it wasn’t just his ‘Quite frankly, my dear’, Rhett Butler good looks that attracted me. The man had a towering intellect to match. The real reason I fell for Jeremy Beaufort was because he’d graduated from the College of Really Erudite Personages. Besides his MBA, fluent Latin and French, and reputation as the Scrabble ninja, he just knew so much. Wagner’s birthplace, the origins of the Westminster system, that the Lampyris noctiluca and the Phosphaenus hemipterus, though commonly known as glowworms, are in fact beetles, that the Bunker Hill Monument is in Massachusetts . . . Hell, he could even spell Massachusetts.

‘Is that an unabridged dictionary in your pocket or are you just pleased to see me?’ I teased him on our first date.

My main claims to fame (apart from a Mastermind know ledge of Jane Austen’s unfinished novel, Sanditon, T. S. Eliot’s pornographic limericks and all the anal-sex references in the novels of Norman Mailer) were knowing how to gatecrash a backstage party at a rock gig, put a condom on a banana using my mouth, and sing all the words to ‘American Pie’. Jeremy, on the other hand, only had Big Talk and no small. While my financial analyst boyfriend found it endearingly funny that the only bank I knew about was the sperm bank, I found it hilariously charming that when I mentioned the Marx brothers, he thought I was referring to Karl and his comrade Lenin.

Jeremy was so good-looking you wouldn’t even consider him as date material unless you worked fulltime as a swimwear model. I was a lowly English teacher with a moth-eaten one-piece Speedo and literary aspirations. So, why did I get to play Lizzie Bennet to his dashing Darcy? To be honest, I think it was mainly because my name wasn’t Candida or Chlamydia; he’d come across too many upper-class females curiously named after a genital infection. These women not only owned horses but looked like them. They could probably count with one foot. If you asked for their hand in marriage, they’d answer ‘Yeah’ or ‘Neigh!’ After years of dating and mating with such mannequins, he told me that he found my spontaneity, mischief, irreverence, sexual appetites and loathing of field sports liberating. And then there was my family.

Jeremy, an only child, rattled around in an alooflooking country mansion, while our Southwark garden flat was crammed with books and musical instruments and paintings waiting to be hung and delicious kitchen smells and too much furniture – a home which was comfortable with its lot in life. As were we. And Jeremy loved it.

Whereas meals at the Beaufort mansion were sober, ‘Pass the mustard’, ‘Drop of sherry with that?’ semisilent affairs, dinner at my house was a riot of heady hilarity, with Dad arabesquing about the place in a tatty silk robe quoting from The Tempest, mother denouncing the Booker Prize shortlist whilst shouting out clues from the cryptic crossword and my sister and I teasing each other mercilessly. Not to forget the various blow-ins. No Sunday lunch was complete without a bevy of poets, writers, painters and actors, all regaling us with richly honed anecdotes. To Jeremy, my family was as exotic as a tribe from the deepest, darkest jungles of Borneo. I wasn’t sure whether he wanted to join in or simply live among us taking anthropological notes and photographs. In his world of strained whispers, my family was a joyful shriek.

While the Beauforts were meat and three veg, Yorkshire pudding people, the only thing my family didn’t eat were our words. Garlic, hummus, Turkish delight, artichokes, truffles, tabbouleh . . . Jeremy devoured it all, along with Miles Davis, Charlie Mingus and other jazz musicians, and foreign films, and performances by banned theatrical groups fleeing from dictatorships like that in Belarus, whom my father was always bringing home to crash on the overcrowded couch.

And, to be honest, an allergy to my father’s excesses is partly why I fell in love with Jeremy. Jeremy was all the things my feckless father wasn’t. Employed, trustworthy, stable, capable, hard-working, as dependable as his expensive Swiss watch. Nor was he the type to come home with a nipple piercing or purple pubic hair, as my pater had been known to do. Whereas my dissolute dad ran up debts like others ran marathons, Jeremy was as reliable as the mathematical formulas he pored over at his investment bank. The man put two and two together to make a living.

My father, a character actor from the Isle of Dogs, had a lemon-squeezer-diamond-geezer accent. My mother, an alabaster-skinned, willowy woman from Taunton, Somerset, boasts a sing-song accent, as though everything she says has been curled by tongs. Her lilt makes other accents, including my own South London twang, sound flat to my ear. Except for my beloved’s. His voice has more timbre than Ikea. Just one word in that dark-chocolate baritone of his could calm all chaos.

But not now . . . Now, in the doctor’s consultation room, he sat mute as sadness flowed down his face from brow to chin.

‘Lucy, it’s clear something is wrong with the boy. Face facts,’ Jeremy finally said, all staccato stoicism. ‘Our son is mentally handicapped.’

I felt the sting of tears in my sinuses. ‘He’s not!’

‘Pull yourself together, Lucy.’ With his emotions now held in check, my husband’s voice was as clipped and precise as that of a wing commander from a Second World War film.

We drove home from the hospital in numbed silence. Jeremy dropped us off and careened straight back to his City office, leaving me alone with Merlin and Merlin’s Diagnosis.

Our tall, anorexic Georgian house in Lambeth, which we’d bought cheaply as a ‘renovator’s delight’ – sales spiel for ‘completely dilapidated’ – leans tipsily into the square. It’s just like all the other houses in the street, identical in style, paintwork, latticing, flower boxes – except for the little boy inside. My son was sitting on the floor rolling a plastic bottle back and forth, rocking slightly, oblivious to the world. I scooped him up and crushed him to me, a hot smudge against my neck. And then I began the agony of self-doubt.

Was it something I ate whilst pregnant? Soft cheese? Sushi? Or wait! Was it something I didn’t eat? Organic tofu, perhaps? Or maybe I ate too much? I hadn’t just been eating for two, I had been eating for Pavarotti and his extended family . . . Was it the glass of wine I shouldn’t have drunk in the final trimester? Was it that one martini at my sister’s wedding-anniversary party? Was it something I should have drunk – like puréed beetroot? Was it the hair dye I’d used to brighten up my bouffant when pregnancy made it lanky and dull? But, oh my God! Wait. Maybe it wasn’t me at all? Did a teenage babysitter drop him on his head? Did the nursery heater leak carbon monoxide? Did we fly with him too early on that holiday to Spain and burst his Eustachian tubes, leading to a seizure and brain damage?

No. It must have been the negativity I’d exuded while carrying him. Merlin wasn’t planned. He’d come along two years into our marriage. Even though we were excited at the prospect of parenthood, I had slightly resented the unexpected intrusion into our extended honeymoon. The only time in my life I wanted to be a year older was when I was pregnant. It’s putting it mildly to say that I didn’t embrace the moment. In fact, I shunned it. I didn’t feng shui my aura in yogalates classes chanting to whale music like Gwyneth Paltrow and Organic Co. Instead, I moaned and complained and railed against the dying of the waist. Especially as I’d recently spent a whole week’s wages on lacy lingerie to celebrate our anniversary. I said to anyone who would listen that ‘Pregnant women don’t need doctors, they need exorcists.’ Birth seemed Sigourney Weaveresque to me. ‘Get this alien out of my abdomen!’ . . . Could too many caustically black-humoured jokes have affected his genes?

But stop. What if it was the difficult birth? Why do they call it a delivery? Letters, you deliver. Pizzas. Good news. This was more like Deliverance. Forceps, suction, the episiotomy . . . Was it telling the doctor that I now knew why so many women die in childbirth – because it’s less painful than going on living? Or perhaps it was the flippant remarks I made in the delivery room to my mother as we peered at the scrunched-up little blue ball I’d just brought into the world? ‘I’ve just given birth to a baby, but I don’t think it’s mine.’

On and on I fretted. I would stop worrying occasionally to change a nappy – usually the baby’s. But for days after The Diagnosis, a San Andreas of fault lines ran through my psyche, coupled with an overwhelmingly protective lioness-type love, waiting, watchful, my claws curled inside me. I kissed my baby boy’s soft, downy head all over. He coiled into the circle of my arms. I held him close and cooed. I looked into his beautiful blue eyes and refused to believe that they led inwards to nothingness. The doctor had reduced him to a black and white term – ‘autism’. But the prism of my love bathed him in bright and captivating colours.

I had to save him. It was Merlin and me against the world.

The Boy Who Fell to Earth Kathy Lette

Told with Kathy Lette's razor-sharp wit, this is a funny, quirky and tender story of a mother's love for her son - and of a love affair that has no chance of running smoothly.

Buy now