- Published: 18 July 2023

- ISBN: 9781761049736

- Imprint: Vintage Australia

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 320

- RRP: $32.99

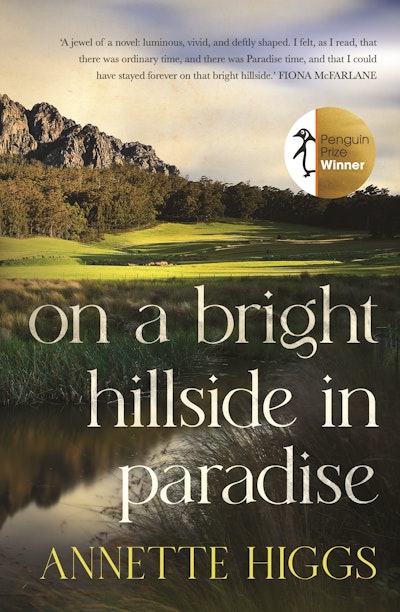

On a Bright Hillside in Paradise

Winner of the 2022 Penguin Literary Prize

Extract

Starlight spilled down the flanks of the mountain. Gradually, lopsidedly, the sphere of a gibbous moon rose above the rocky ridge, casting silver light below. A stage seemed set.

In the moonlight a creaking wagon pulled by lumbering bullocks weighed down by their yokes rolled along a track. Following bush trails, other carts and wagons headed in the same direction. People tramped the tracks too: husbands, wives, some with babies; girls, boys, little running children. Lines of light marked out the course of the crowd. Hurricane lanterns swayed from the wagons while young men held aloft flaming torches of pitch-dipped manfern stumps blazing like captured stars.

The bush soon opened out into Duggan’s paddocks and a brightly lit barn appeared on the hillside. All the trails of light converged upon it. The farm boys brought their flambeaux and stuck them in the ground around the perimeter of the barn, forming an irregular ring of light.

Inside the barn, lanterns flickered in the lofty rectangular structure, the largest in the district. A murmur rose as the crowd pushed their way in. People jostled, found positions. The air glimmered yellow, fading to an indoor twilight in shadowy corners. With the autumn harvest not far off, a store of hay would soon fill the space, but tonight it was empty, ready.

Underfoot, a layer of chaff carried the faint scent of vegetative decay. A row of blue-painted wooden chairs from Mrs Duggan’s kitchen stood ranged along the front of a low, makeshift platform. Duggan himself, short and fat, supervised these chairs, making sure no-one sat on them. He spread his chubby arms wide and asked the women to keep back, keep back, please. The chairs seemed to promise something special, something mysterious.

Wives and mothers wedged themselves onto hay bales set out around the barn walls. They roosted, chattering in low voices, their children sitting cross-legged on the floor at their feet. Nearer to the front, bearded men clustered in groups by the platform with anticipation. It had no decoration, no props, no sense of a stage or an altar. It was a clear, open space of possibility waiting to be filled.

Younger boys, adolescents, lounged against the barn walls, nonchalant. They formed a tight knot close to the doorway and the starlight outside, ready to escape if the show turned out to be a lot of rubbish after all. A skinny boy with a prominent Adam’s apple picked up a straw and chewed the end of it, one ankle crossed over the other. As a rustling in the air suggested proceedings were about to begin, another boy leaned close and urged him towards the front. But the boy with the straw shook his head. The other shrugged and pushed forwards alone, elbowing others out of the way.

A commotion arose. Two figures in black coats and flowered waistcoats entered through a side door near the front of the barn. Anticipation rippled through the hundred-strong crowd; heads craned, pleasurable shivers quivered up the backs of necks. The murmuring increased – then died away at some inaudible cue, as if they had all paused at the edge of a precipice.

The two men, strangers who had arrived in the district unannounced a week ago, stepped up onto the platform. The older man, clutching a Bible against his waistcoat, stooped as he climbed awkwardly, even though the platform stood only about a foot off the ground. His shaggy white beard gave him the look of an elder, a Moses figure, about to impart mysteries. He stood to one side, lifted his shoulders and stared over the crowd with glittering eyes. The other man, spry, trim, with a hint of red in his whiskers, leaped to the front of the platform and like a young commander of troops, raised one arm. The crowd hushed expectantly.

‘Brothers and Sisters,’ he began, ‘may the Lord bless us as we meet together.’

He spoke with a musical Scottish brogue, an attractive deep baritone. The sound of his voice, muffled at first by the smoky air full of chaff dust, the odour of cattle and the gentle anticipatory murmurs of the crowd, gradually grew in volume with a power that cut through the warmth and close fuggy smells.

He raised his chin. ‘Bless the singing of your praise, the reading of your Word!’ The words resolved, became clearer, and took on a sing-song rhythm. ‘Bless our prayers and let them be heard! Bless us as we meet together, dear Lord!’

Shuffling noises filled the barn, the soft sounds of a hundred people breathing. The sharp odours of perspiration and anticipation joined the animal smells of the barn. The mesmerising voice spoke on, words of peace and rest and blessing and promise. The preacher strode up and down, turning now and then with a wide gesture of his arms to encompass everyone.

Echo Hatton, fourteen years old and thin as a stick, sat on a disintegrating hay bale wedged between her grannie Eliza and her mother Susannah. She huddled against her mother’s generous breast as she had done as a little girl and fingered the small treasures she kept in her pinafore pocket: a stone from the creek, a few dried mushroom caps.. It was as if the preacher made her uneasy. Looking up, she saw her mother’s eyes wide and staring, her mouth open, her pink lips damp with a slick of saliva. The baby on her mother’s lap slept, forgotten. Echo stared at the other women, the other mothers and daughters and grandmothers. They all bent like sunflowers towards the front of the barn, attracted by the speaker with the waving arms.

The rhythms changed. The preacher’s sing-song prayers metamorphosed into a hymn. Round, deep notes reverberated through the golden air. Within a few minutes some in the crowd, women with shining faces, joined in. Low murmuring spread among the grandmothers and children, the bearded men and the young girls.

Soon the pull of the hymn had reeled everyone in. ‘What a friend we have in Jesus, all our sins and griefs to bear!’ Those who didn’t know the words hummed. The old hymn lulled with the rhythm of a mother rocking a baby in her arms. ‘O what peace we often forfeit, O what needless pain we bear, all because we do not carry, everything to God in prayer!’

As the last chorus died away, the yellow light of the kerosene lamps flickered in the dusty air.

The young preacher intoned into the quiet, ‘Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light.’

These were the words of Christ from the Book of Matthew, he reminded them, waving his Bible aloft ; words addressed to everyone here tonight as much as they were back in the Biblical days. ‘For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light,’ he repeated. He strode up and down the platform, his patterned waistcoat flashing under his coat. His mesmerising voice, starting low, rose in volume. His tone, gentle and persuasive at first, grew in force and urgency. Throwing both arms wide, he stepped forwards as if he would plunge into the crowd.

‘Come unto me says the Lord!’

Spittle flew from his lips.

‘And I will give you rest!’

An uneasy stir rippled through the crowd at this. Women turned to each other, wiping away tears. Cheeks were flushed, eyes glistened. Some of the young men leaning against the barn walls chewing on straws threw the straws to the ground, lifted their shoulders, and pushed their hats back on their foreheads. One or two widened their stances and crooked their arms akimbo, fists on hips. The women sitting on the hay bales began to rock back and forth to the rhythms of the singing, the preaching, the praying. The air in the barn thickened, warm and stuffy; the dim lights trembled. Female voices began to cry ahs! and ohs! and other noises, strange and guttural.

The girl Echo could no longer make out what the preacher was saying. The pure sound of his voice reverberated around the barn like a rebounding answer, though the question remained mysterious. His words seemed full of promise and rightness and peace and rest, though how these blessings would come upon them wasn’t clear. Perhaps a miracle was about to happen. The girl’s mother, Susannah, began to sway like the other women, moaning a little.

‘You all right, Mother?’ Echo whispered, grabbing her arm above the elbow.

Susannah didn’t answer. She stared at the two preachers, both pacing rhythmically holding their arms out to the crowd, waving their Bibles high. The smaller children hunched their knees to their chins, wide-eyed. In the middle of the crowd a woman stood, stretched out her arms, and swayed as if she might fall. An inarticulate note rose from her, hovered in the air – an entreaty of some kind? – joyful and fearful at the same time. As the younger preacher stepped down from the platform and moved to greet the woman, the crowd parted. She pressed forwards and fell into his arms with a gulping sob. Leading her to the row of blue chairs, he bent over her, spoke low, patted her shoulder. She went on sobbing. As the preachers’ vivid chant – Come unto me, all ye that labour – spread ripple-like through the barn, other women followed. They stumbled to the front, huddled on the chairs and dabbed their eyes. Singing started up again, ‘Blest be the tie that binds, our hearts in Christian love . . .’

Another woman leaped to her feet, an eruption from the sea of people. She sobbed and cried, shook and screamed, struggled against her family who tried to hold her. The crowd around her shrank back, but the younger preacher called reassurance, ‘The Holy Spirit is upon her!’ Faces turned with fascination to watch the weeping woman. Helping hands lowered her to the ground, held her shoulders. She drooled and groaned. ‘Our sister is blessed!’ cried the preacher, and the people turned to him in wonderment at the strange spirit he had brought among them.

Beside Echo on the hay bale, Susannah bent forwards and groaned low. Echo scooped the baby from her mother’s lap so itwouldn’t roll unregarded to the barn floor. Susannah’s eyes, bright with tears, stared at the platform; the flesh of her cheeks quivered. Panicked, Echo looked around for help, for her father or her brothers, but she couldn’t see them anywhere. Susannah continued to groan, as if she were in pain.

The old grannie, who had been intently observing the show, seemed to notice her daughter’s affliction. ‘Ay, what is up with you, Susannah?’ she asked, grabbing her wrist.

People began to stand and move; he barn became a confused crush. When Echo looked towards he young men near the barn walls hoping to spot her brothers, what she saw made her flinch. Shouting and waving their balled fists, the youths seemed drunk, or angry. The hubbub became frightful. An unseen wind had infiltrated the barn, blowing out several lanterns. Susannah’s face wavered in and out of Echo’s sight as if lit by flashes of fire. The girl closed her eyes and screwed up her face.

How long all this went on, no-one afterwards could really remember. At times it seemed brief and events flashed past; at other times it seemed the night stretched on and on. When the people of the district looked back, this evening always seemed like an island in an ocean of days. It seemed to mark a before and an after.

Finally, when supplicants filled all Mrs Duggan’s kitchen chairs, when the hubbub in the barn had resolved into a dazed aftermath, the preachers raised their arms and pronounced a blessing. Boldly upright, open palms outstretched, eyes raised heavenwards, they covered the people in benediction. ‘The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make His face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the Lord turn His face towards you and give you peace!’

Sighs of peace! rippled through the barn. There was more shuffling. Neighbours turned to neighbours and embraced. What a fine thing is a revival! And to think their own district had been touched!

Descending the platform, the two preachers approached the row of women on the blue chairs, sank to their knees, took work-roughened hands in theirs, and spoke in low, intent voices. The women wiped their eyes with dirty handkerchiefs and the edges of their skirts. Husbands moved towards them hesitantly.

Near the barn door, a tall young fellow with an angular face and a battered hat pulled low on his forehead stepped out into the cold starlight and spat. Eddie Hatton followed him, pausing to take a deep breath. Pulling his tobacco pouch from his pocket, he unwrapped his pipe and pressed a pinch of shag into the bowl. ‘Got a light?’ he asked the tall fellow, who obliged by reaching into his britches pocket for a box of matches. Eddie offered his tobacco pouch in return, and the fellow filled his own pipe. Eddie watched closely, but the bloke took only a modest pinch.

‘What d’you reckon about all that?’ Eddie asked.

The tall fellow sucked in a lungful of smoke, then puffed out slowly. ‘Wouldn’t surprise me if they was all drunk. Acted like it, didn’t they?’

Eddie snorted in agreement. He wasn’t sure if the fellow was referring to the preachers or their audience, but he agreed either way.

Eddie’s older brother, Jack, had stayed inside the barn. Moving against the tide of the departing crowd, he pushed towards the platform, as if he wanted to speak to the preachers. But they had their backs to him, bent over the women. Hesitating, Jack turned away to join his father who was making his way towards Susannah and the children. As Noah Hatton came up to his family, his face inscrutable behind his thick beard, Susannah held out her arms.

‘Oh, Noah!’ she whimpered.

She said no more and he stared at her, looking unsure. Echo held onto the baby, her face screwed up in puzzlement. Eventually, Noah patted his wife’s shoulder and said, ‘We’ll go home now.’

Jack leaned close to his father, his face rosy. ‘Did you see, Father? Did you see?’

Noah looked from his shaken wife to the bright visionary eyes of his son. He shook his head, and said again, ‘We’ll go home now.’

On the way home, walking beside the rolling bullocks with his whip on his shoulder, Jack began singing the last hymn. His voice, not long broken, skidded across the notes, sometimes falsetto like a child and sometimes growling like a man. ‘Blest be the tie that binds, our hearts in Christian love . . .’

It sounded tuneless and ugly, but his grannie, surrounded by little children in the back of the wagon, seemed to like it. ‘Bless me heart alive, it’s a lovely one, Jack,’ she called over the creaking of the wheels. ‘A person can really hum along with that one.’ She gave a little cackling laugh.

Echo gazed out into the darkness though she couldn’t see much. One hanging hurricane lamp cast a faint glow on the track ahead. The moon came and went behind greyish clouds. Eddie, walking alongside the wagon, smoking, said nothing until Echo leaned over and asked him, ‘What do you think, Eddie?’

He turned towards her. ‘I reckon they put on a good show, young Eck.’ He nodded once, his lips twisting into a half-smile she couldn’t interpret.

The family drove on, home to their farm in Paradise.

On a Bright Hillside in Paradise Annette Higgs

From the winner of the 2022 Penguin Literary Prize.'A jewel of a novel: luminous, vivid, and deftly shaped.'FIONA McFARLANE

Buy now