- Published: 29 March 2022

- ISBN: 9780143792154

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 352

- RRP: $24.99

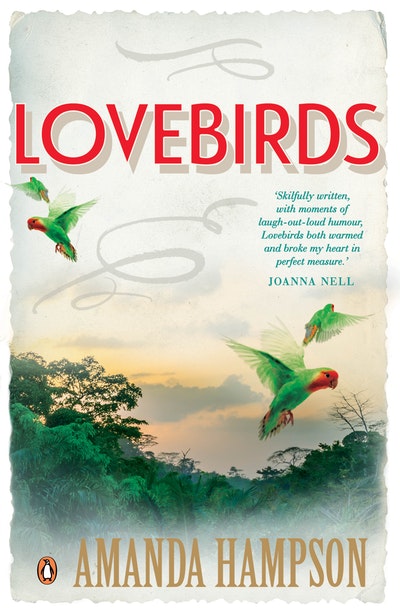

Lovebirds

Extract

Eric made no comment. He’d been subdued for the last couple of days, which was most unlike his usual chatty self. He’d been the only witness to Elizabeth’s gusts of furious tears as she railed against the world and all the dreadful people who survived while beautiful souls like Ginny were taken early. But in his silence, Elizabeth sensed a quiet empathy. He was giving her space to grieve.

She hung the grey linen dress, bought some weeks ago in preparation, on the front door handle. It wouldn’t do to forget that. Everything else she could work around. She added an extra couple of shirts, a pair of loose pants and a jumper to her overnight bag: comfortable clothes to wear around the house. Paul would want to talk, of course, and she would be there to listen and commiserate. Paul and Ginny had been her closest friends for more years than she wanted to calculate, and Ginny had been her best friend for half a century.

Eric perched on the windowsill where he could watch the birds in the garden and admire his own reflection at the same time. He had other favourite spots: the back of the sofa, the picture rail and sometimes on Elizabeth’s shoulder or head while she cooked dinner. He liked to walk over the crossword as she puzzled over it and, even though he was no help with clues, she counted that as participation. It wouldn’t do to forget him either.

She offered him an upturned finger. He looked up and tipped his head to one side, bright-eyed. She thought he looked particularly handsome in the morning light, almost regal with his turquoise breast, stripy head and tiny necklace of black spots circling his white throat. She rubbed his chest gently with her finger and he gave a little shiver of pleasure.

‘Hello, pretty boy,’ she said in her most loving voice. ‘Hello, sweet thing.’

‘Hello sweet thing,’ Eric chirped. ‘Swe-et thing sweet thi-ng.’

Elizabeth found herself smiling for the first time since she’d heard that Ginny had gone. Clever little bird. If it wasn’t for Eric, there would be whole days when she didn’t hear the sound of her own voice. She sometimes joked around with him in different accents. She did a passable Stallone – ‘Hey, wise guy’ – and Bogart – ‘Here’s looking at you, kid.’ It was hard to tell how amusing he found her but she enjoyed hearing him repeat these phrases.

Most people assumed that budgies were barely one up from goldfish in the thinking department, and while Eric was no towering intellect, not given to reciting poetry or expounding his political opinions (both points in his favour), he was intuitive and a quick learner. He wasn’t just a feathered echo chamber; he had excellent recall for phrases as well as tone and nuance, and often added consoling little tuts. Sometimes he would rub his head against Elizabeth’s knuckle in a show of spontaneous affection and she knew that, in his own budgie-ish way, Eric loved her. In the past, she had considered getting a female to keep him company, but was unsure how she would feel about Eric lavishing his attentions on a lady friend.

Now that she had a firm grip on her emotions, she could be strong for Ginny’s family. She would find words of comfort for them, and offer a shoulder to cry on for Ginny’s children, Adam and Polly. She would deliver the eulogy, which she had worked on late into the night, with emotion but without tears. She didn’t want to impose the rawness of her grief on anyone. Privately, she wondered if she would ever get over this loss. After a lifetime of friendship, it was difficult to imagine a world without Ginny.

Eric normally lived in a large palatial cage on a stand and she transferred him to a smaller cage for the trip, fixing the latch carefully. ‘Come on, young man,’ she said. ‘We’re going on a road trip.’ His tiny eyes brightened; there was nothing he loved more than a car trip. It was the closest he came to flying.

‘I can’t bear it I can’t bear it,’ he chirped.

‘That’s all behind us now, sweet thing,’ explained Elizabeth, making a note to teach him a fresh phrase on the road. He had a Siri-like ability to pick up phrases and could be tricky to reprogram. It wouldn’t do for him to repeat this one in Paul’s hearing.

She walked around the house one more time, glancing briefly into each room. She’d lived in this house for more than forty years. Every room held memories of different stages of her life: as a young married woman, as a mother to babies and then two growing boys. With Ray and without Ray. She had once been the central figure here, but her sons had been gone for years. They had families of their own, and she had drifted into the periphery of their lives.

The house was 1950s solid cream brick, unprepossessing from the outside but the rooms were large and the ceilings high. In the living room, glass doors opened onto a paved patio and sunny garden. In the garden was an elm tree that she and Ray had planted as a sapling. Now it had wide generous branches and she often sat on the bench in its dappled shade on summer afternoons. The house had once brimmed with music and life and slamming doors, but these days it was quiet. The only disturbance was Geoffrey next door with his industrial leaf blower that roared like a jet taking off. Around and around his house, up the ladder and on to the roof, then out to the pavement, up and down the grass verge and finally the street and gutter. No leaf left behind.

Until recently, her neighbour on the other side had been Maud McBride, who was very elderly and too frail to go out. By prior arrangement Maud would hang a gaudy souvenir tea towel from Fiji in her front window when she needed Elizabeth to shop for her, change a lightbulb, take out her rubbish or track down a strange smell in the kitchen – of which there were many. She’d recently gone into care and Elizabeth was surprised how much she missed her, or perhaps missed being needed. That house had been empty for a while, but now there was a new resident, a young man with dreadlocks who kept putting his bins out in front of Elizabeth’s house. She hadn’t spoken to him yet but had left a couple of terse notes, spending as much time writing them as debating whether to sign off ‘Elizabeth’ or ‘Mrs O’Reilly’ – settling on the latter to emphasise the seriousness of the matter.

Now it was time to go. She gathered her things and locked the front door carefully. She secured Eric’s cage on a booster in the passenger seat of her car. He babbled companionably as they set off into the thick of the Sydney traffic towards the freeway and, beyond, her old hometown of Nullaburra.

In her late teens, Elizabeth had famously run away from Nullaburra with no plans to ever return. But life was longer than she could have imagined at seventeen and she’d returned countless times over the years to see her parents, while they were alive, and Ginny and Paul. These days, there was a pleasant familiarity as she entered the outskirts. She rarely went into the centre of town, taking the first turn-off and crossing the river as she headed directly to Ginny’s place. She always looked forward to her first glimpse of the white double-storey house on the hill with its generous verandahs and gingerbread trim. She had first visited as a child and it had never lost its sense of wonder.

As she drove up the long curving driveway, she was disappointed to see a couple of cars parked in front of the house. It would have been nice to have Paul to herself for a little while so they could have a proper talk. Paul evidently felt the same because, before she had even switched off the ignition, he appeared on the verandah and came down the front steps to meet her. She got out of the car and almost collapsed weepily into his embrace before remembering she was to be the strong one.

‘Liz, so good to see you.’ Paul held her at arm’s length and looked at her closely. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Of course,’ she said thickly. ‘It’s not like we haven’t been expecting it.’

He nodded. ‘Come on in. We have a full house – the kids are here.’

Elizabeth sensed a discomfort in Paul but it wasn’t the time to question him. She lifted Eric’s cage out of the car and handed it to him. ‘Just let me get my bag out of the back.’

‘Leave it there for the moment, Liz. As I said, we’ve got a full house, so we’ve had to billet a few people out.’

Elizabeth’s face set in the stony expression she knew, from past experience, people often took exception to and she attempted to loosen it, forcing a tight smile. It was appalling to hear herself bundled up with ‘a few people’. Who on earth were these people? Ginny wouldn’t have allowed her to be ‘billeted’. Or perhaps she would, actually. On reflection, Ginny would have told her to pull her head in and not make a fuss.

‘Of course, no problem,’ said Elizabeth. ‘I’ll fit in with you, Paul.’

Paul wrapped an approving arm around her shoulders. He made squeaky kissing sounds at Eric, who lifted his beak in the air disdainfully. After a moment, he gave Paul a cheeky sideways glance and said, ‘Hey wise guy wise guy sweet thing.’

Paul laughed out loud and Elizabeth was pleased that Eric had worked his charms on cue. She took the cage back from Paul and they made their way up the wide steps to the front door. At the top of the stairs, Elizabeth paused to turn and gaze out over the property; the marching rows of vines wreathed in bright green were a sight that always brought her pleasure. It felt like a homecoming just to be here with Ginny’s family.

As they crossed the verandah Paul said, ‘I’m sorry, Liz. I know you’d prefer to stay here, but with the kids and their families, that’s literally every bed in the place taken.’

‘No, no. It’s my fault. I didn’t think. I should have booked into the motel.’

‘No need for that expense. Judith’s more than happy to have you at hers.’

This stopped Elizabeth in her tracks. Ginny’s sister was the last person she wanted to stay with. Surely Paul knew that? Surely Judith knew that?!

‘What’s up?’ asked Paul, pausing to wait for her.

‘Nothing. My knee just locked up,’ she improvised, giving her knee a cursory rub. Her only thought was how to extricate herself from this awkward situation. She didn’t enjoy staying with other people; Ginny and Paul were her only exception. This house was her second home and they always referred to the bedroom off the verandah as ‘Lizzy’s room’ – and why Judith would offer to have her there was anyone’s guess.

As she entered the hallway, with its polished timber floor and familiar smell of beeswax and lavender, Elizabeth felt a crushing pain in her chest at the absence of Ginny. It knocked the breath out of her and put the trivial matter of her own temporary displacement in perspective. It was only for a few days.

Paul led the way to the dining room, a high-ceilinged room dominated by a conservatory table, where Elizabeth had enjoyed countless meals with the family over the years and, before that, with Ginny’s parents and siblings when she was young.

Adam and Polly and their partners sat around the dining table, which was covered in dishes of food in containers of various shapes and sizes, presumably dropped in by well-wishers. By rights, thought Elizabeth, these should have gone into the freezer for Paul to have in coming weeks, instead of being consumed in one decadent feast, and in the middle of the afternoon! There were half-a-dozen bottles of wine open, and everyone looked wrung out. Polly’s two daughters and Adam’s young son lay on the Persian rug beneath the bay window, playing a board game – just as Ginny and Elizabeth had done as children. That, at least, was a wholesome scene.

Adam got up from the table, gave Elizabeth a hug and sat down again, but his wife, Abigail, and Polly and her husband barely acknowledged her. Elizabeth had pictured herself in warm embraces with Adam and Polly, reminding them how much their mother loved them and how special Ginny had been. She’d imagined it like a scene in a sentimental American film where the character of Elizabeth was played by an actress who exuded warmth and empathy, who murmured words of wisdom that were received with tearful gratitude. The real Elizabeth stood marooned halfway across the room holding a birdcage, her arm lifted in an awkward salute that she quickly withdrew as the two couples resumed their conversation.

Elizabeth had known Ginny’s children all their lives. She’d been present at their births and marriages. Over the years, she’d had intimate knowledge of their personal lives: Polly’s struggles with fibroids, Adam’s low sperm count, Abigail’s drink-driving charge. She heard it all, although never from them. But Elizabeth could see that she had already been demoted to someone who had once known their mother.

When the grandchildren noticed Elizabeth, they jumped up and galloped towards her, squeaking with excitement, stretching their hands towards Eric’s cage. Eric fluttered his wings as he retreated backwards into a corner. Elizabeth felt a flush of panic and briefly considered dashing for the safety of her car. Why didn’t someone stop them? The parents thought it was funny, for God’s sake!

‘That’s enough, kids,’ said Paul gently. ‘Budgies are highly strung, so you mustn’t touch him.’

‘Aww.’ His granddaughter pouted. ‘Can’t we just pat him?’

‘No, you can’t,’ said Elizabeth, instantly regretting how abrupt she sounded. The parents stopped laughing. The children stopped jumping. The room went still and silent. Elizabeth softened her tone. ‘Budgies are very sensitive. Stress can kill them.’

Through clenched teeth, the child released a piercing shriek that rang in Elizabeth’s ears for a full minute like a distant train whistle. The girl began to weep and retreated to her mother’s lap. The two boys threw themselves resentfully back on the rug as though their board game had been reduced to second best. Polly stroked her daughter’s hair, perhaps imagining the child had been traumatised by being refused something she wanted.

Elizabeth put Eric’s cage up on the mantelpiece safely out of reach. She took the cover out of her bag and placed it over the cage. As she turned back to the room, she caught sight of Paul shaking his head slightly at Polly, as if to dissuade her from some course of action. He turned to Elizabeth. ‘Come into the kitchen, Liz. I’ll make you a cup of tea.’

‘Tea time,’ confirmed Eric. It was one of his favourite expressions. ‘Tea time.’

Elizabeth followed Paul down the hall to the kitchen at the rear of the house. As she passed the large gilt-framed mirror that hung in the hallway, she caught sight of herself and, as often happened, took a moment to recognise the woman she saw there. The body shapeless in comfortable pants and cotton shirt. The faded hair, short and sensible. The stubborn set of the jaw. As always, she had the urge to dispute this image. Insist that this was not really her, but some trick of the light. Or perhaps it was a trick of life, one that everyone experienced sooner or later. The only part of herself that she recognised was that flicker of uncertainty in her hazel eyes. She often saw it in photographs, even those taken of her as a child, and was never sure if it was visible to other people. Ginny recognised it, of course. And Ray – he could read her eyes.

She gave this imposter in the mirror a kind smile and noted the immediate improvement. But from the dining room, she heard Abigail say, ‘Aye, aye, m’hearties!’

Polly said, ‘Watch out or you’ll find yourself walking the plank.’

Adam suggested they keep their voices down but Abigail just laughed her dirty laugh. She was often rude to Adam, and Ginny too, when she could get away with it, and flirty with Paul. Elizabeth had never liked her and she probably knew it.