- Published: 11 February 2025

- ISBN: 9781761344558

- Imprint: Penguin

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $34.99

Half Truth

Extract

ONE

Hobart

7 April 1999

My grave is open. For forty days it sits, ready, waiting. I might avoid the fall. I might not. Will someone close my bones when this is over? Feed me soup? Steam my skin, anoint me with herbs and oil?

I breathe deep as I crest a wave of pain, fists clenched.

Focus. I’m serious, Zahra. Keep. Your. Shit. Together.

And it’s over.

I collapse, arms falling against the plastic lining of the makeshift pool in our living room. Monks drone Gregorian chants from the CD player on the shelf, and the acrid scent of clary sage hangs heavy in the air. My naked belly emerges from the water, mountainous, volcanic. Outside, afternoon light filters through the leaves of the walnut tree, just now beginning to turn autumnal reds and yellows. As stillness descends, a ringing phone ricochets through my momentary zen.

‘Hi. You’ve called Zahra and Jacob. We can’t get to the phone right now. Leave a message and we’ll call you back.’ My voice sounds weirdly perky

‘Zahra, it’s me.’ My mother’s words are thick with fear. ‘Just seeing how you’re going. Umm, anyway, thinking of you. Call us when you have any news.’

And it’s back. I set my jaw, steel myself. I’m surfing a monstrous ocean, black whirlpools swirling beneath me. All I can do is not fall in, fight the urge to let it consume me.

Stay up, Zahra. Stay up.

Jacob touches my arm, whispers, ‘Good work.’ My senses are electric, his touch excruciating, breath rank. What the fuck has he been eating? It comes to me. Pickles. But I can’t talk. Not now, because I can’t lose my balance. Stay up, Zahra. Stay up, stay up, stay up . . .

It’s over.

I let out a mangled sob, feel my heartbeat slow.

Hiss the words, ‘No. More. Fucking. Pickles.’

It’s back again, and off again, and back again and off again until the waves crash, relentless against my body, and I can no longer come up for air. I remember that when there are no more breaks, it’s almost over, and sure enough, in ten minutes time, I’m on my hands and knees beside the pool, bearing down.

‘Can you see? It’s your baby’s head!’ The midwife holds a mirror between my legs, and Jacob makes a strange sucking noise. Horror or wonder, I can’t tell.

‘Stop. I can’t. I just want this to be over. Ugh.’ My words finish in a stream of vomit. With each retch, fluid gushes from my vagina, breasts dripping, snot streaming from my nose; liquid from every orifice. ‘I’m leaking!’ I am hysterical, out of control. Ridiculous.

And then, I am pushing, my body expanding beyond itself, beyond the edges of the world. I open my mouth, and as if called forth by my screams, my son’s head is born. And then, once more, the earth of my body ruptures and I am a mother. Sobbing, broken, euphoric.

Dark curls are plastered against his wet, pink head.

A wrinkled, old-man, alien version of my face stares up at me.

I begin to cry.

He looks like me.

I’ve never met anyone who looks like me before.

TWO

Cloudy Bay, Bruny Island

1 May 1999

In the last of the evening light, I stumble as I collect an armload of rough-hewn logs, my hand brushing against the pouch of loose brown skin that hangs over the top of my trackies. I smell of sweat, rancid milk, and the dark earthiness of my maternity pad. I disgust myself. From inside, a wail, imperceptible to all but a new mother. My cracked nipples pierce with pain as the milk begins to flow.

Shit. He’s awake. It’s scary how pissed off it makes me.

Hurrying, I dump the wood next to the fire, and rush down the hall, pausing to turn the kettle on for tea I already know will be drunk cold. Breasts dripping, I bend over the bassinet where my baby shrieks.

Pink and spotted, he is animal-like: fragile, breakable but somehow wild, like nothing I can do could ever contain him. I know I love him, but the jumbled mix of ferocious anger and bone-crushing love shocks me. I live in the whitewash, constantly knocked by waves of rage and helplessness. What have I done?

The autumn wind howls up the hill from the ocean, and the tips of my fingers are numb as I reach for him. I carry him to the lounge, sit on the torn velvet couch and try to breastfeed, flinching as he latches on to the broken skin of my nipple. I yelp, and Jacob looks up from the page where he’s scrawling garden plans in black pen. His shaggy blonde hair is greasy, and he’s giving me Kurt Cobain vibes. A few years ago, I would have found it hot, but now he just looks second-hand, spent.

‘Everything okay?’ he asks.

I blink back tears. The question is ridiculous. Of course nothing is okay.

But I don’t say anything. There’s no point. He’s struggling too. There’s so much to do.

‘I’m fine. We need to get unpacked, though,’ I say, looking around. There are boxes everywhere. Like fools, we have upended everything, moving last week from our rental in town to our first real home, a fibro shack at the end of a dirt road, overlooking the windswept Southern Ocean. Isolated, alone, with a three-week-old baby. No wonder I’m wrecked.

‘Yeah, okay. I’ll get to it.’ Jacob is oblivious to the disaster of our home and gives zero shits that neither of us know where the good coffee pot is. ‘What do you think?’ he says, turning around his paper. Circles and lines map out his vision for the garden. Raspberries, apple trees, chickens. A herb garden, a potato patch. Other stuff. Maybe goats? Fuck knows.

I shrug. ‘Looks good. I guess.’

Jacob’s mind pinballs between obsessions; music, painting, boats, psychedelics. Gardening is his latest thing. A few months ago, he did a permaculture course and now all he thinks about is self-sufficiency. Mainly because he’s preparing for the collapse of civilisation at the end of the year, when the millennium bug hits. Apparently, he tells me, heat flushing his pale cheeks, food systems will mess up and we’ll all have to live on potatoes and silver beet or whatever else he’s planning to grow here. Y2K.

Sometimes I think he’s hoping for it, to be proven right, like he’s outsmarted the mob. That all he wants is to prove he can survive here, with nothing, just him and his garden and the hydroponic crop in the back shed.

But I don’t want to be here forever. Turns out I’m not the earth mother I imagined I would be when I first saw the house two months ago, pregnant and dreamy. Naive. Stupid.

It’s hard to believe just six weeks ago the late summer sun was still hanging in the sky, the last of the raspberries still on the cane, the apricots squishy at the bottom of the tree in our rental in the city. I was taut, round and full, happily babysitting the girl from down the street. Learning, I thought, how to mother.

We thought babysitting was practising, but really it was pretending, I know that now. We thought borrowing a child was like having your own, in the same way some say having dogs is like having babies covered in fur, just because you love them and clean up their crap. But that’s bullshit. Being a mother rips you apart. It takes the world as you know it and fucks it up, squeezes it, tears at the fabric of your existence and leaves you thinking, Where the hell am I? And what the hell just happened?

My thoughts must be all over my face because Jacob’s forehead screws up, concern furrowing his thick brows. ‘Why don’t you call Mel?’ he says. He’s outsourcing my emotions again. I’m too hard to deal with.

Shooting him a dirty look, I punch her numbers into the phone on the wall, collapsing on the lounge with a petulant sigh.

It only rings once before she picks up. ‘Hey,’ she croaks, husky.

‘Are you hungover?’

‘Just a bit.’ She laughs. ‘Big night, too much fun. What are you up to?’

‘Just more of the same.’ I sigh, pulling a sodden breast pad from my bra and scanning the bucket of shitty nappies soaking in the corner. She tells me about a band she saw last night, the cute boy she kissed at the afterparty, and my cheeks ache. When she hangs up, I feel worse than ever. I’m twenty-two. Why am I here, living this life? This was a mistake. I should never have had this baby. The dream is unravelling. I am unravelling.

It’s not like it was an accident. I wanted this baby. My body was hungry for this child. The longing was a heavy ache of wanting in my soft caramel belly, even though I knew I was supposed to know better, to want better for myself. After all, my mother told me I could be anything I wanted. But I knew what that meant. Anything impressive, anything successful, anything more interesting than just a mother. A doctor, or an academic, like her. But still the seed grew, month by month, taking root, tendrils working across my body, consuming my thoughts entirely.

The baby bump of a passing stranger made my heart constrict; when I came across a tiny yellow knitted cardigan at an op shop, buttons shaped like flowers, I was compelled to have it. Sheepishly, I offered up my money to the white-haired woman at the counter of St Vinnies, who smiled at me and proclaimed my purchase lovely. Once home, I shoved it deep towards the back of the cupboard, where no one else could see my shameful, reckless desire.

I wanted a child, a family, a home. But I didn’t know, not like I know now. Tears prick at my eyes. I didn’t know.

I push the thought away, cover it with positivity. At least I got pregnant. The doctor told me I’d most likely be infertile, so it was literally a miracle.

The conversation was not so long before the seed took root. I sat on the hard plastic seat in the doctor’s office, wearing a long blue velvet skirt and cut-off singlet top, pimples still angry on my post-adolescent skin. I was trying to understand my cycles, asking if the rage I felt in the week leading up to my period was normal. My gut told me it wasn’t, that I wasn’t; there was something profoundly wrong with me. Once a month I was untethered, out of control. I frightened myself, and then, just when I deeply believed I was broken beyond repair, I would begin to bleed, and the anger would drain away, leaving me embarrassed, ashamed. The doctor sent me for an ultrasound on my pelvis and diagnosed me with polycystic ovaries; quite common, she told me, no big deal. Only thing is it can cause infertility in some women.

Just a throwaway line, just something she had to mention. No big deal. The word stuck in my chest like a knife.

Infertility.

I never knew what to do with my life, never had any passion or direction besides a general, often overwhelming, sense of justice, right and wrong. But I always, without question, knew I wanted to be a mother. At least, I thought I did.

Because now I am.

And I suck at it.

My regrets have lodged themselves in my throat, and I’m struggling to breathe.

I call Mum. She’s the perfect choice – she’ll remind me of everything I should be grateful for. Relentlessly optimistic, my mother has never let me feel sorry for myself – negativity, sadness or self-pity was not allowed in my childhood home. Think positive, focus on the good is always my mother’s approach.

‘Hi, darling, how are you? How’s my beautiful baby boy?’

‘Still not sleeping. He feeds all night. I’m exhausted.’ My voice is whiny. I hate how I get with her, all childish and pathetic. Desperate.

‘Oh, dear. Still, sounds normal for a healthy little one. At least you don’t have a sickly child, like Jennifer from across the road. Her baby screams all day long, poor thing. You’re so lucky he never cries!’

‘Yeah, you’re right. He’s always happy.’ I bend over and kiss his fuzzy head, guilty for my complaints.

‘I wish I lived closer. I’d take him so you could sleep. Still, at least it’s beautiful where you are. How’s that view looking today? Is it very windy? Can you believe you can see the ocean from your balcony? Incredible.’

She’s right of course, it is beautiful here, especially in the early morning, the slate-grey clouds rolling over the vast Southern Ocean, the cold buttery sand littered with bull kelp and shells, shattered by waves which crash at least a hundred metres deep. A couple of times, while Jacob and Amir are asleep, I’ve walked down the hill, through the bracken-lined pathway to the beach, watched the bruised sky turn the mist-covered ocean from silver to deepest blue. Alone, barefoot, I walk across the wet sand, breathing in rotting kelp and sea birds, stumbling over rocks slippery with dew and seaweed. There, by the water, I can pretend there’s a chance one day I’ll wake up and the feeling I’m all out of place will be gone.

I say goodnight to Mum, hand the sleeping baby to Jacob and head to the bathroom.

This is my favourite room in the house. The walls are a rich blood red and a huge claw-foot bath sits in front of a giant window that looks towards the ocean. Tonight is a frame for millions of stars and a sliver of crescent moon.

I turn the cool silver taps, peel off my grubby, milk-stained clothes, averting my gaze from the flesh beneath. My stomach repulses me. It shouldn’t matter, but it does. Before, it was smooth and taut, a soft curve of brown flesh, peeping out between the low rise of my floor-length skirt and the crop of my black tank. But now, lined with angry red stretch marks, separated in the middle, it hangs in two deflated wrinkled sacks, disappointed and empty.

Like me.

THREE

Marrakech

7 May 1999

Khadija looked around at the golden walls, the arched blue doorway, the cave-like salon with the turquoise divan, the grapevines she planted long ago, now grown thick and lush across the lattice at the top of the courtyard. Fifty years she had lived in this small riad inside the walls of the medina of Marrakech, fifty years since she arrived from the village a new bride, still a child. And yet soon it would be time to leave. Above, the last load of washing was hanging across the rooftop terrace, the last pot of couscous steaming on the burner in the small, tiled kitchen.

Her back ached; it rarely stopped these days, but she still had weeks’ worth of work to do, and only five days to do it. Not that she would do the heavy work, no, her son, Abdul Karim, would handle that, but since her husband died, there was no one else to do the sorting. And so, cupboard by cupboard, she picked over her life, all the bits and pieces of ordinary stuff that had stuck it together.

On either side of her was a pile. One to keep, the other to throw away. In the ‘keep’ pile so far was a birthday card from her neighbour, Laila, a report card of her youngest daughter, Nour, from her final year at lycée (mainly Bs) and an unused bottle of cough syrup that might still be good. In the ‘throw away’ pile: an envelope labelled ‘Factory 1979’, a birthday card she forgot to send, and a letter whose words had faded so much she no longer knew who it was from.

She sighed. She was too old to be packing all her things into boxes, making neat arrangements from the scattered pieces of her life. Maybe it was a mistake, moving after so long in the one place? But still, she went on, picking through the stuff of every day, occasionally finding amongst it something special, something ethereal.

Of course, in truth it was all just stuff. But some things, Khadija felt, were imprinted with their history, her history. These things, a few special things plucked from the ‘keep’ pile, she set apart and placed in a large thuja wood box, the Hand of Fatima carved into its chocolate-toned lid, the centre of the palm inlaid with green stone. Khadija knew she was collecting her box of moments, or at the very least, as close to them as she could get, given how hard they were to hold on to.

For as long as she could remember, Khadija had noticed moments that other people missed. Slippery and impossible to catch, they crept up on her, endlessly arriving and passing by. As a child, she tried to capture them, lock them away like a bird in a cage, staring, wide green eyes unflinching, breath held, ready. 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. Aha! She would blink hard.

But every time, just as soon as her eyes were open, they were gone. And then there were those that crept up on her, the ones she didn’t see coming, but once they had her, were impossible to cast off. The moments that split her life into now and then, the ones that followed her and jumped out from tiny details like the scent of amber or the light on a summer afternoon. The ones that showed up uninvited to her dreams, both awake and asleep, shaking her each time with the same violent force as they did the first.

Khadija knew already this box wouldn’t be packed with all the other things, when the time came to travel from her tiny home inside the warmth and noise of busy Berrima to the new concrete home, four stories high around a central courtyard in Douar Dlam, on the outskirts of Marrakech. Instead, she planned to hold it in her lap, cradling it gently as she had once cradled each of her four children, each now grown and married with their own children. Except perhaps for Ahmed. She still didn’t know about Ahmed.

Douar Dlam was a new suburb. The city sprawled out into what were once rocky desert fields where nomad tribes would camp when they arrived to sell their wares in the narrow souks of the city. Hamid had always dreamed of a home this big, one where all the family could gather for Eid under the same roof, the sound of laughter echoing against the coloured tiles. Khadija remembered their conversations all those years ago, and it gave her comfort to imagine his joy if he knew the factory he worked in every day for fifty years, even as it ceased to produce the rope that fed and clothed their children, had nevertheless left her with money to build this home.

Hamid’s factory, while only two metres wide, had stretched over four hundred dark metres inside the orange walls of the medina of Marrakech. And so, when she heard the King was intending to buy back the walls surrounding the old city, she knew this would be the way she built the big house, the family house. The settlement was generous, allowing her, with Abdul Karim’s help, to commission the home she would soon move into, alone – until, inshallah, her firstborn son came back, and they held the family gathering she’d dreamed of all these years.

Khadija opened the thuja wood box, looking once more at the collection of items she had found. A necklace left by her mother; smooth chunks of amber, strung on leather; a silver Hirz pendant, the three coins hanging from it rubbed smooth. Wrapped in an old piece of her sister’s scarf was the bracelet Hamid gave her when Ahmed was born, and the last photo she had of Youssef and Ahmed together. In there too were the papers she had copied when searching, and cuttings from the newspapers: one neatly folded, and the other crumpled into a small ball many years ago.

Slowly, breathing deep, she smoothed out the newsprint, slightly yellowing at the edges. Her heart sank again, just as it had in that awful moment. The moment she knew her son was gone. Gently, she flattened the wrinkled paper, running the tips of her fingers across the story she wished more than anything she could rewrite.

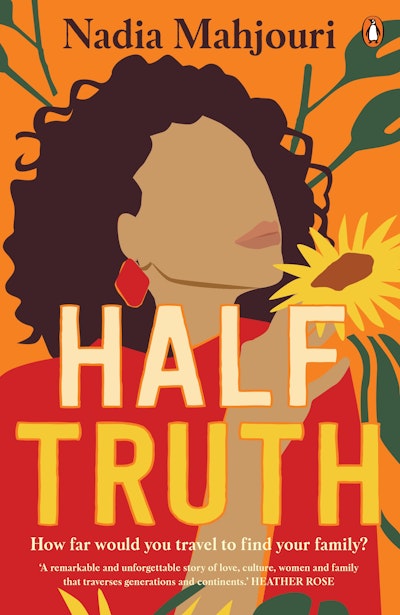

Half Truth Nadia Mahjouri

A daughter searches for her father; a mother for her son. From isolated Tasmania to vibrant Morocco, two women seek the truth about what happened to the same man.

Buy now