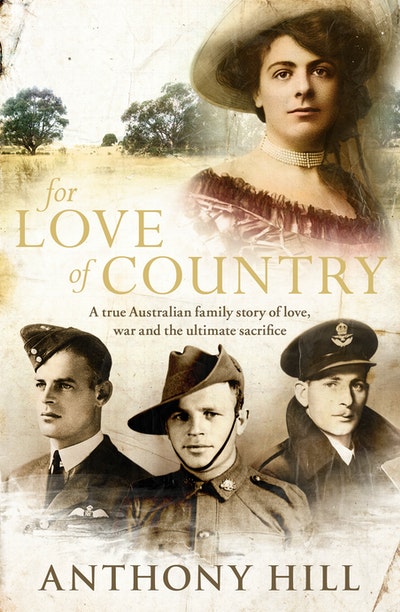

Behind the unforgettable scenes of For Love of Country.

In his brilliant new biographical novel, For Love of Country, Anthony Hill tells the story of one resilient, funny and charmingly ambitious Australian family torn apart and bound together by the two World Wars. Here he answers our questions about unearthing the Eddison family’s story of life during wartime, and offers insights into his processes.

Let’s start with Captain Walter Eddison – tell us a little more about his war service, and the long-term ramifications on his personal life and that of his family?

Walter Eddison was indeed fortunate that the gas he inhaled was not lethal, and that the dose seems to have been relatively small. It was enough, however, to put him in hospital for three months. He didn’t return to the front but had a desk job as quartermaster for the rest of the war. As his strength returned he went back to farming, migrating to Australia with his family in 1919. The aftereffects lasted for the rest of this life: he would become breathless and tired easily, increasingly so as he aged. I’ve necessarily had to reimagine the exact circumstances of the gas attack, based on the battalion’s war diary which records the event. I was struck how, when the gas masks were inspected a few days later only ‘very few were found to be defective!’ Unlucky for the men wearing those few. Still, there were many points at which the masks could become frayed in the stress of active service. I also used the gas mask as a metaphor for Walter’s internal distress as each of his sons died in the Second World War. He didn’t express his emotions in words – he usually left the room when his sons were mentioned – but his feelings ran very deep.

Can you explain what these soldier-settlement packages offered by the Government were, and their rate of success?

Soldier-settlement schemes were established towards the end of the First World War (and also the Second) to provide acreage on which returned servicemen and their families could (hopefully) establish a living for themselves. It was part of State and Commonwealth pledges to create a ‘land fit for heroes’ for those who’d sacrificed so much in the Great War. The trouble was that many of the blocks were too small or the soil too poor to sustain a proper living. Many of the settlers lacked sufficient capital or farming skills to make a go of it. Many city-dwellers were unable to adjust to rural life. The farms began to fail in increasing numbers – in many cases the settlers just walked off the land, shutting the gate behind them. Soldier-settlers in the Capital Territory also struggled with high rents and economic recession, but they were fortunate the Territory government was sometimes able to offer more land to make the farms viable. Rent rebates and more favourable leases eventually made it easier to survive the Great Depression. Even so, people like the Eddisons struggled until the wool boom of the early 1950s.

While her husband Walter, and her three sons, all fought for the British Empire, Marion made sacrifices of her own as a ‘bush wife’, and developed a small supportive network of women. Can you tell us a bit more about these women, their contribution to the war effort and the developing nation?

Marion Eddison was quite an anomaly as an Australian ‘bush wife’. Her neighbours’ wives almost all had either been born to the land or grew up in rural districts. Marion, however, came Southampton in Hampshire, from a well-to-do upper middle class family. Through her mother she had connections with the aristocracy and even the royal family. At finishing school Marion had been taught to make dainty cakes and sandwiches for the afternoon tea table – not how to cook stews and roasts for a hungry farming family. She knew how to embroider lace doilies, but not how to darn socks and sew buttonholes. All these things had to be learned when she went onto the land, and for a long time, she wrote, she had ‘a big hate on’. Yet she eventually came to accept it and to acquire all those skills a mother needs to be the anchor of a large family. She always retained her ladylike manners and bearing – seeming somewhat queenly to the neighbours who always called her Mrs Eddie to her face, never Marion.

The Eddisons became a very a well-known family in Canberra. When did you first learn the full extent of their story?

I first heard of the Eddison family and the sacrifice of their three sons in 1994–5, when I was writing the libretto for a choral work ‘Spirit of Place’ to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the pioneer church of St John in Canberra. The Eddisons worshipped there and a memorial plaque to Tom, Keith and Jack is on the wall of the church. When I was casting around for a story that might encapsulate the experience of the returned soldiers after the First World War, my cousins John and Esther Davies suggested the Eddison family. I immediately took it up: the story of the Great War, the soldier-settlement schemes, the Depression of the 1930s and the outbreak of the Second World War – with all the tragedy that meant for the individual and the country – says much about the experience of the generations in Australia in the years before and after the two World Wars of the twentieth century.

In For Love of Country the whole narrative is rich with the sights and sounds – and indeed smells – of the places and times you are writing about. How did you manage to achieve this?

This is not a question that I can properly answer. All my life – as a child, a journalist and an author – I have been fascinated by history and also by story. In my recent books I seem to have found a way to combine the two interests. I call them ‘biographical novels’, in which the external facts are as accurate as I can make them through detailed research, travel to locations and interviews with living witnesses. That’s the journalist at work. But the most important parts of any story are the internals of thought, speech and emotion – the inner journey which brings the characters to life on the page – and that can only come from myself and my own reimagining of the story as a novelist. Traditional historians may be aghast; but I can only say that, when I begin to write, if Captain Cook is not talking within a paragraph or so of meeting him there is – for me and my story – something terribly wrong.

Can you describe your daily routine as an author and researcher and what else you have to fit into your routines – apart from writing?

I’m what they call ‘a morning person’, which means that most of my creative work is done by lunchtime. Afternoons are for revision, reading-in for the next stage of the project, gardening, swimming and playing the piano. Much of my research and notetaking is done at the National Library of Australia, close to where I live in Canberra, with its unrivalled online facilities and collections of books, maps, manuscripts and photographs. Even when composing and the need is paramount to escape telephones and other interruptions, I’ll often take the iPad to a desk at the Library to complete the work started earlier that morning. Original composition is generally done in the early hours – anytime from 5 o’clock onwards when I wake, tap away in bed on the little iPad and send the work to myself by email for later editing and revision. I don’t write for any set length of time but have a minimum target of 200 words a day: it is often more, but never less. It means each day one more page gets added to the pile. The other part is that I always stop – always, invariably – when I know what the next sentence is to be. The rest of the day is letting it roll around in the unconscious, building on what has gone before and laying the course for what is to come next. Frequently I’ll dream it, so that when I wake the following morning the next words are usually in the mind ready to be tapped out and emailed to myself. Certainly the technique helps me to avoid the horror of the black hole of writers’ block, from which neither light nor words can escape.