Paul Kennedy answers our questions about writing Fifteen Young Men.

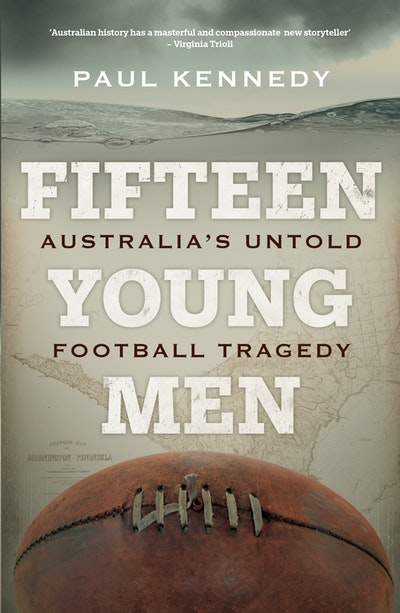

In Fifteen Young Men, journalist Paul Kennedy tells the story of an 1892 maritime tragedy that saw fifteen young men of the Mornington Football Club perish in rough Victorian seas. Revealing the stories behind the tragedy, Kennedy captures the trauma of families and friends suffering almost unbearable loss, but he also evokes a snapshot of Australian life at the time. Here Kennedy answers our questions about the research, writing and emotion behind the book’s creation.

The story of doomed adventure has a compelling narrative and a cast of colourful characters – what about it captured your imagination?

The relationships between the players and their families in such a small town are the most powerful aspects of the story. Also, the concept of fate versus bad luck. The Caldwell brothers – Jim, Willie and Hugh – for example, were all athletic but had never played a game of football together until that day. Jim decided on the morning of the game he was going to play! How long they may have talked to each other after the accident, while slowly dying (or did they die quickly?), was at first a shocking thought. But after researching their family history I became more interested in their lives than their deaths. And, of course, all the other players were related in some way, either biologically or through friendship, work, school or community activities.

How did you come to the realisation that you’d write this book?

I think I have always wanted to write about the story. I was looking for a story to write about for my fourth book and I didn’t have to look far. I have close ties to the area, having lived nearby most of my life. The men in the story played for the Mornington Peninsula premiership (although far more unofficial in those days). In 2007 I was a playing coach of the premiership-winning team (Seaford) in the same competition, and I have been senior coach of the Mornington Peninsula representative team in Victorian state-wide carnivals. I also know what it feels like to lose a teammate to accidental death. In 2010 my good friend Donny Epa was hit by a train. I have dedicated the book to his memory.

Can you give an idea of the level of research involved, and to what lengths you went to ensure you got the story straight?

The book written and published in 1909 by Alice Caldwell (sister of Jim, Willie and Hugh) was important to the research. Letters from the Allchin family descendants were also critical. For a few years I nibbled on the copy of old newspapers by scrolling through archives at the State Library – reading every edition of the South Bourke and Mornington Journal and Mornington Standard from 1885 to 1893. And for the last year I have lived on Trove – a brilliant resource. The snippets from those newspapers gave the story colour and truth. And through the old print I discovered previously unknown facts about the characters in the book.

Did you ever feel like you’d gotten in over your head (pardon the pun)?

I never felt overwhelmed by the story but I did cry while writing some parts of it. This is not a bad thing for a journalist. It is evidence the story is important.

Beyond the facts, the book offers a snapshot of the time, and gets deep into the emotional reactions of the people involved. How do you know you’re hitting (or missing) the ‘emotional truth’ of the different parts of the story?

I will be interested to know what readers think of the storytelling. Only they can decide if I hit on the emotional truth. I know the reporting is strong and without sensationalism. I resisted natural urges to imagine and speculate. Editor Patrick Mangan was brilliant to work with. He helped me stay focused on the boys and their families’ stories.

What was something you discovered during your research that surprised you?

I was surprised and interested by everything from that period in our history. The Depression of the 1890s was starting to really bite in 1892. Football was not only popular, it was necessary! A serial killer (Deeming) was hanged on the same long weekend the accident happened. And Collingwood was in its first season. Actually, the story of the dress-up fund-raising match staged at Victoria Park in the winter of 1892 still gives me a laugh. Also, the death of the Caldwell brothers’ mother surprised and saddened me, to say the least.

You live on Port Phillip – how did your personal experiences of the places visited in the book feed into the writing?

I have lived and played and coached football in the district since I was eight, so I know the game well. Also, I know this stretch of coast intimately. I am familiar with the tide’s movements and the weather’s moods. Throughout the heavy research phase of the book I ran daily along the beaches and looked at the water, imagining what the players went through that night. I am not by nature a spiritual person but I was regularly moved by the experience. When I went boating with local couta sailor Peter Sydes we were joined by a pod of dolphins, shooting through our wake. It was another humbling moment.

What challenges did you face in balancing historical information with flourishes of movement and colour?

I tried to control those urges to provide too much flourish. The story is gripping enough. I have tried to tell it simply, with genuine warmth.

In your opinion why is this story important in terms of Australian/Victorian history?

All history is important because it gives our lives context and meaning, and local history is as vital as national and international events. Among other things, this story is about the significance of sport to communities, particularly through dark times. It explains as well as any other story why Victorians are forever faithful to our native sport.

How would you describe your level of AFL fandom?

In my humble opinion, Australian rules is the best game in the world. After family, my two great devotions are football and writing; this book gave me a chance to combine them. I barrack for Seaford (my local team) and Collingwood, and always will.