- Published: 30 March 2021

- ISBN: 9781529112160

- Imprint: Vintage

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 240

- RRP: $24.99

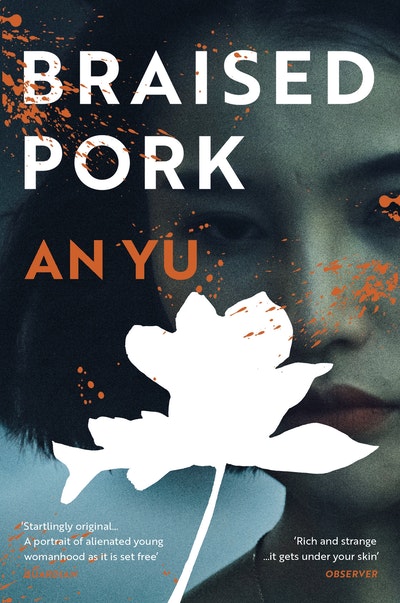

Braised Pork

Extract

1

The orange scarf slid from Jia Jia’s shoulder and dropped into the bath. It sank and turned darker in colour, hovering by Chen Hang’s head, like a goldfish. A few minutes earlier, Jia Jia had walked into the bathroom, a scarf draped on each shoulder, to ask for her husband’s preference. Instead she had found him crouching, face down in the half-filled tub, his rump sticking out from the water.

‘Oh! Lovely, are you trying to wash your hair?’ was what she had asked him.

She knew well that he would not pull such a joke on her. But was it even possible for a grown man to drown in this tub? She checked his wrist for a pulse and bent to see whether there were bubbles coming out of his nose. She called his name, stepped into the bath and grabbed him by his torso to lift him, so that at least he could be the right way up. But he refused to budge, rigid like a broken robot.

The ambulance was on its way, or so they said. Jia Jia sank to her knees on the beige-tiled floor. She pulled the plug so the water could drain. It was the only thing she could think of doing now; maybe, without the water, Chen Hang would be able to breathe again. Crossing her arms on the rim of the bath, Jia Jia observed her husband’s body as if he were a sculpture in a museum. She had never seen such stillness. She was certain that this was the first moment of silence she had spent with him in their four years of marriage: even when they slept, there were always sounds – his snoring, the air conditioning, cars on the streets. But she could not hear anything now. His crouching body appeared to be growing greyer and thinner, like dried and unglazed clay that was going to fall apart. Jia Jia felt suddenly like vomiting, realising that she had not been breathing either. She covered her mouth with her palm and tried to think about something else. She thought about how long it took for a body to grow cold after death. A few minutes? An hour? A few hours? She did not know. The humidity pressed down like hands on her throat, and the marble bathroom that had always been far too large seemed too small in this moment, suffocating for the two of them. It became clear to Jia Jia that Chen Hang must not have considered, not even for a moment, that such a place was improper for a death. He had not thought about his wife, who was going to be the first to find him, who was going to be alone when she did, and who would certainly be forced to wait before anyone else would join her in that bathroom. He had not pictured her in those few minutes after discovering him there, naked and dead, because if he had, he would surely have chosen another way.

During their breakfast that morning, Chen Hang had muttered, with a sigh and a mouthful of pickled cucumber, that perhaps it would be a good idea to resume their annual trip to Sanya. This was the first time anything encouraging had come out of his mouth for weeks. He had called off their holiday the previous year for unspecified reasons – presentiments, Jia Jia had feared, of his increasing lack of interest in her, and their marriage. He had never loved her, no, she knew that much. She was not a fool. But they had promised each other a lifelong partnership, held together if not by love, then by their declared intention to have a family. And so as long as he had assured her that he intended to remain married to her, everything else had been forgivable.

‘When will we go?’ Jia Jia had responded immediately, Chen Hang still chewing on the cucumber. ‘I’ll start packing after breakfast.’

‘Whenever you like. I’m going to have a bath.’

‘A bath?’

Jia Jia knew that Chen Hang had never been a man to have baths: he found no pleasure in soaking himself in hot water and preferred to shower, believing it led to cleaner results. She wanted to enquire further – she quickly swallowed her food, drank some water, and opened her mouth to speak – but decided to keep her silence for fear of irritating him with her questions and forcing him into a bad mood so early in the day.

‘Don’t pack too much,’ he warned her, bringing the bowl of congee to his mouth and eating what was left in one gulp.

Jia Jia heard him put in the plug and start the water. It was November and she had just finished organising their wardrobes for winter. She opened his suitcase, mounted a chair, and reached into the upper compartment of the wardrobe for his summer clothes, refusing to let herself be distracted for fear of forgetting something of his. She was not going to let that ruin their trip. Let him have his bath, she decided, let him have his time alone.

By this point in their marriage, packing for Chen Hang could not have been simpler. The first time Jia Jia had prepared his suitcase for him, for their honeymoon, it had been a disaster. She had taken too many pairs of socks and forgotten his chess set. After that trip, she had quickly learned to arrange his suitcase to his liking: to roll the underwear and fold the polo shirts, arrange the chess set so that it would be nestled safely even after the suitcase was checked in, and leave a small space in the upper right-hand corner for his cigars, which he would pick out himself.

Packing her own belongings was more challenging this time. She had not been able to shop for new clothes – something Chen Hang always told her to do before they travelled.

‘Go shopping,’ he would say. ‘Get some of that new stuff in the windows. You’ll look nice for the beach. And you’ll be happy.’

Maybe she should go shopping tomorrow. But Chen Hang had explicitly told her not to pack too much. Was there a financial issue? Was something going wrong with his business? Again she wanted to interrupt his bath and ask him. Why are you having a bath? You never have baths. Is something wrong at work? She was his wife, not his mistress, she had the right to know. But she felt afraid, as she often was with him, to dig up something that he would rather have kept buried.

Ultimately she decided to check on him anyway, to see if the bath had soothed him. Perhaps he might even open up to her naturally. So she picked out the two scarves, one orange and one floral, waited a few more minutes, rehearsed her smile, and gently pushed open the bathroom door.

She should have asked him at the very beginning, at the breakfast table. Now, her questions had to be swallowed back into her stomach. In fact, in that way, nothing had really changed, and this thought made Jia Jia feel insuppressible resentment and disgust towards the man she had let herself be married to. She ran to the toilet and vomited, unable to hold it in any more, her eyes tightly shut. He had betrayed her. Abandoned her. Failed to honour the one thing he had promised her. Everything about him became pitifully repellent; his brows contracted even in death, belly hanging like a pouch, head balding.

When she lifted her head, she noticed a piece of paper resting on a pile of towels near the sink. The paper was folded down the middle, opening and closing slightly in the stillness of the bathroom. It was as if the paper were alive. Jia Jia reached for it, revealing a drawing of a figure – a fish’s body with a man’s head. It was sketched by Chen Hang – she knew his crude style well enough.

The body of the creature had a curved spine through its centre and scales across the surface. Even from a rough sketch, it was evident that the large tail was powerful. The picture had been drawn in a rush, but the human part of it, unlike the rest, was handled with a great deal of precision. The head seemed to be a detailed portrait, everything was there: the wrinkles, the nose hair that stuck out a little, the swollen bags under its eyes. It was the head of a man whose eyes looked straight through the viewer towards a distant horizon. It resembled an ID photograph, neither laughing nor frowning. Nothing about the face was special except perhaps for the overly large and bare forehead. It showed no signs of a curious past or an exciting future.

Jia Jia remembered a dream that Chen Hang had told her about. He had been in Tibet, alone, for what he had called ‘a spiritual escape from all this crap’. Though Chen Hang was not a religious man, beyond tossing money into donation boxes whenever he was in a temple or a church, he would go, periodically, on these trips by himself. Jia Jia knew that he needed them, but for what, she would rather not consider. She often reassured herself that she was his wife, the woman of his home, and he was a man who had selected his life partner with much consideration, a man who would never desert the woman he had chosen, even if at times his heart rested in someone else’s bed. So for every one of his trips, Jia Jia had packed for him, sent him out the door, and waited for him to return.

This recent trip, perhaps a month ago, had been Chen Hang’s first time in Tibet. One night while he was there, he had called Jia Jia and described a man who had appeared in his dream.

‘He was barely a man,’ he said. ‘In fact, he was a small fish served on a plate, and everybody was eating it. We ate it all, every last piece of meat. Even the bones. But just when we started digging into the head, it began to talk. Boy, was I scared! I’m surprised that didn’t wake me up. When it began to speak, I noticed that it wasn’t a fish. It was a man. The man was talking, laughing, and telling us that he was late and we should not wait for him to begin our meals. I can still hear his roaring laugh.’

He had not remembered the rest of the dream and he had not known who the man was. Jia Jia did not give it too much thought at the time. The only thing she did remember thinking was that Chen Hang must have been alone for him to call her in the middle of the night, that at least on this trip there had not been another woman in his bed. In fact, she had forgotten entirely about his dream until now, because after Chen Hang returned from Tibet, he had not spoken about the fish or the man again.