- Published: 3 July 2017

- ISBN: 9780143770299

- Imprint: RHNZ Vintage

- Format: Hardback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $34.99

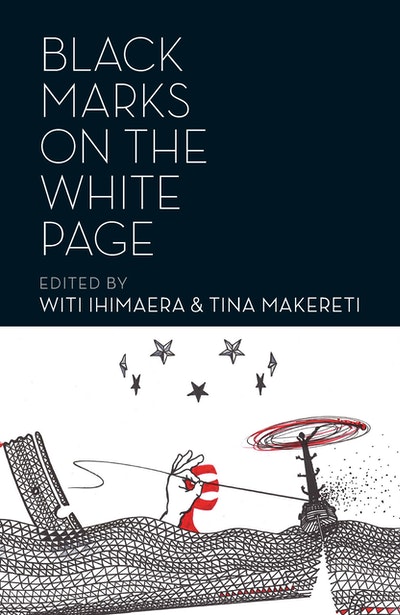

Black Marks on the White Page

Extract

Make noise like the tarakihi instead, girl; train your ear to their clacking applause, singing with voices like the roaring rain, we say, calling for mates from between the leaves.

We see the dog. We see him come round the back of the house. We see him. Lolling panting hound wolf. Hound of god. Nah that old kuri been here for donkeys, we say. Mangy beast. Bloody dog animal. We don’t like your dog, girl. Dangerous teeth. Hazard. Bloody hazard. Our kotiro chooses tane like dogs. Wild boy men. Pretend heart. Savage.

Our girl loves church. That Jesus. Her best tane, all the kuia say. Rubbish. Rubbish, say the koro. Rubbish, say the whaea. Leave all those kuri behind. Sing your big song, girl. Listen to the cicada; make your voice loud, girl, loud.

Jesus didn’t put that pepe in there. Get off your knees.

She left him. Kawhena with her rolling gait and massive puku, walked away from her ahi ka and her tane and her kainga. For herself she could do nothing, but for her baby she could raze heaven.

Make noise, Kawhena, whisper the kuia. Patere start small. The drumming? Safe. We say. Safe Pepe. She’s going to change the world, this girl.

She carried us inside, from the flanks of Ruapehu up to Tamaki-makaurau on the overnight flyer. Her phone lit up, over and over, the whole way so that she barely slept. She thought about hiffing it out the window but there was no money for a new one. Her parents, Nick, her friends, all calling and calling. The bus stopped under the Sky Tower and she had nowhere to go. In the toilets she washed her face. She had a month or so before the baby would come and that meant she had to find a place to stay. Her duffel bag was heavy. She put it on to balance out the weight of her stomach, and turned toward K’road. It was going to be a hot one. The few trees she passed were already alive with the tympani of cicadas. At home she used to lie on her bed and listen to them through the open window. Make noise, Kawhena, they’d say.

He had seduced her. Or she had seduced him. Or both. In Korea. Nick was there teaching English too. From her home town. Turned out it was common to go overseas and meet someone from right where you left. K’road reminded her of Itaewon. Dirty streets perfumed with a strange combination of seaweed and steak. Vendors in their dozens, hawking and disdainful because here in the American quarter you were probably associated with GIs, and everyone hates someone.

She would wander like a kite whose string was uncertain and if pulled tight may not hold. She could hide here but still make noise, throw her voice like the ventriloquist cicada. Throwing her voice so no one could tell where she was standing, where she rubbed her legs together from, nor her wings. She felt stupidly free.

She walked in the wet heat with a singlet on, and an umbrella. She liked the feeling of a moist tongue on her skin, the way lovers feel from sweating after sex. Like that. Rise up, Kawhena, she heard. Sing. The smell was cos of the heat. Cos of rotting cabbage. And people. And smoke. And the clinging tang of alcohol.

The prostitutes in Itaewon looked like they were straight out of a movie; hanging on the door jambs of their rooms in narrow crooked streets, eyeing each passer-by for the hint of cash and the fuck-eye — music and incense eking out — as if either of those snake charms would entice the lonely. Those things are really for the ashamed and the secretive. The lonely don’t care.

She took Nick’s hands and led him into the night. Everything comes out at night. Creatures from behind their screens, critters, like the roaches that infested her building, come out to eat, to find a glass of soju, and she had come out with them. Twenty-three years she’d been underground. Longer than most. She came out to be with others, to smell their feral smells, to sweat with them. Everyone lost things here: their wallets, their dignity, their hearts.

The leaves underneath them were damp and soft beneath her bare knees and then her naked back. As though she was being massaged. As though she was being loved from the ground up. From the earth up. Even on the driest of summer days she could detect the wet beneath her. She could smell moisture. You are the rain, Kawhena, she heard. They said. When a tree shed a leaf she could smell moisture leaving it. The wind and sun taking its life second by second. Sending it back to te po.

Her rhythm when on top of him was slow and uncomplicated; maybe it was the heat, or the liquor, or love. It can take a year for a single leaf to pass. We keep vigil for our girl, whisper the whaea. Broken tiny. Pieces, tiny bones. We watch. Shhh. Sometimes when she had sex she felt used up like those leaves. Fallen. Threads of memory where the flesh of the plant had disintegrated and nothing but the whispery skeleton remained. Women are low to the ground, her mother had told her. Hine-ahu-one. They hug it and sniff it, beating their chests and letting their blood run out of them in their monthly grief. Better that than babies, she said. Not better than babies, we say.

Afterwards, she lay talking with him. They were both passionate about the Treaty. About poverty. About changing the world. When they got back to New Zealand they would make a difference. They would clatter and clamour. They would smack their wings against the branches of trees. Under that foreign liquid sky, everything was possible; a noiseless, colourless space, so massive it felt like anyone could start again.

The church rose up in front of her as if it were a beacon. That Jesus, we say. She loves him. Years of wooden pews and rosary beads flooded her memory. The stained glass windows of her childhood were repeated here, throwing a kaleidoscope of colours and feelings onto the floor. It had been too long since she’d prayed, to anyone. To anything. She dipped her fingers in the font, crossed herself as she’d been taught, and sat down.

Perhaps if she hadn’t spent the summer singing. Perhaps if she’d kept her legs closed. Impossible, we say. Find your voice. Find your song. He might not have felt trapped. She might not have felt trapped. They didn’t even like each other. There were only odd jobs and no money. She wouldn’t repeat the cycle. She meant what she said in Korea about doing it differently. About change.

She looked up into the blue eyes of the crucified man on the wall. He looked like Nick. Or Nick looked like him. Dangerous, mutter the koro. Put that dog down. His emaciated body and bleeding hands were supposed to give her comfort. She would sleep here at the foot of this white man for as long as she could. She had no choice.

Our girl planned a water birth. Make noise, Kawhena, we say. Karakia, e koro. Even at eight days overdue she was still hoping for that. Her waters broke first. It doesn’t always happen that way. The labour was so long she thought we would never come out. After the first twelve hours she was numb with fighting but still we didn’t come. No drugs she had told everyone. No intervention. Listen, we whisper. Hear the koro chant.

Nick-kuri stood guard like a sentry, his eye immediately drawn to anything that looked medical. It was something for him to do instead of watch our mother cry and call out. Where are her women, the whaea growl. The koro are making drums. Bring forth your tane, Hine-te-iwaiwa. When he came to her she was at a backpackers. Some church set her up. Gave her a food parcel and put her in a box. She rung him and he came.

Kawhena needs to have a caesarean, the doctors said, crowding and measuring and timing. Our kuri father questioned and grilled them. That baby is struggling to come out, they shouted at him. There will be consequences. Come, tane, come, the koro are loud now. He asked what that meant and would the baby die and what about Kawhena. Haere mai, child. Into the light. He made the decision to not have the caesar and to just continue. They threatened him then. Told him that they would do the operation if the baby was not born in the next hour. They said that the baby was in distress. We are in distress. The doctor looked angry. His beard wobbled even when he wasn’t speaking because he was grinding his jaw. They looked similar in that respect — our matua and the doctor — the latter an older whiter version of our father’s anger, the both of them warring while our Kawhena moaned and sweated.

Kuri-Nick decided; the hospital and all the doctors were not for us. Sing koro. A breath, e tane. It was discrimination. He told mum and the midwife they were leaving and even when the midwife protested and told him to calm down he yelled that she could fuck off back to her institution too. Manawa mai, take heart, one breath.

Anxious koro. Loud koro. Make noise, Kawhena, say the kuia. He grabbed mum’s suitcase and walked her out with her arm over his shoulder, rescuing her. Big man, shout the whaea.

They made it down the long corridor, wide enough for all the other patients to stop and watch the spectacle — momentarily relieved from their own concerns — as our loyal kuri urged our mother on. We can do this by ourselves, he half yelled, half cried, almost carrying Kawhena by now. He was sweating as if he were the one having labour pains and then, on the lino before the door, our girl fell to her knees and called out for the midwife who had been trailing along behind talking to the muscled back of Nick. She too was crying and afraid.

Nick-kuri father bared his teeth. Cornered hound. Lost dog. His face contorted and he urged our mother again to get up. I’m sorry, he kept saying, let’s go back. We can go back, babe. You can make it. But we were somewhere else by then. And Kawhena refused to move. Access your life, e tama. Break forth. The koro turn. Change, the koro chant.

Change, we scream to Kawhena. Now we come. Kawhena hears. Kawhena will have her voice. Several of the doctors including the angry bearded man come to tell the midwife that she needs to move my mother out of the hall and our mother stands up. Back, she roars at them. I don’t need any of you. Back. And there on the blue lino, white knuckles holding the perfectly placed handrail, the koro making the blood thrum in her ears, through excruciating push by push, this woman, this whanau, is born.

We were delivered into our girl’s arms and onto her belly and at her breast. We opened our eyes to the horrible brightness, to tears from Kuri-Nick, and to Kawhena’s glazed smile. In the hall they brought blankets and warmed us and gave us a few minutes. Then they brought a wheelchair and wheeled us back into the birthing room before the placenta had even been delivered. And it wasn’t until after the placenta came that they looked and found a girl.

Our father spoke like a different man, a whimper voice we had never heard. Hello, my little one, he said. When the iho stopped pulsing he cut it. Now this child is born, say the koro. Now the voice is found, say the kuia. Our mother laughed and Nick-kuri smiled back not minding because all that anger of before had passed.

When the midwife checked us over she didn’t find anything wrong, we were already suckling like we’d been doing it forever. Everyone in that room was glowing and exhausted. We felt that. It had nothing to do with our death. If they could’ve, they would have sensed our smile too.

The midwife could never have known that there was something wrong with our lungs, and then our heart. In the moment before it stopped our girl had handed us over to Nick-kuri and he was nuzzling us and calling us his little one. He was the most gentle man he had ever been in those minutes as he lifted us up and put our cheek to his chest. The koro began again. The winds of change. So that the sound of our kuri’s heartbeat could carry us back into the dark.

At the gate, the eyes of the tekoteko bore down from atop wide arms. The rain came, slashing and ripping the world apart. Here Kawhena would bury the tiny box. Here she would bury everything. She stood in borrowed blacks with Nick at her side. They would carry this child home. This was his turangawaewae. Would her dead gather behind her, cluster around, watchful and slightly dangerous, taiaha raised, warriors with one foot cocked back, ready? We are here, we say. Would thick-bodied women blockade the path with song that becomes karanga and tears at you, as if the dead they are calling on exist within you and the whaea are pulling them out tendon by tendon? We will, we say. Would her dead walk towards her with heavy ankles, as though shackles dragged behind them, as though they were the slow prisoners of an army, forced forward to take up their own front line, chins high. We do, we are, we have.

The maihi welcome her. Into the bones we go. Into the womb of Papatuanuku where we do what Maui was unable to. We become immortal. We are not crushed between frightened thighs.

She is not crushed. The rain softens the ground for all the noisy creatures to emerge.

Kawhena is angry so that the muscles in her stomach tense into strands of ropey distress. Her rage has thew but she stands with her dead on the verandah, maihi holding the house up above her. She has changed since Korea. She has changed since every single thing that went before this moment. She does not invite you in. She does not welcome your dead to come and mingle with hers. She is no longer the friendly native.

Our girl lines up, we line up, the women and her, along the porch with linked arms. We line up with them, her, our dead. Those who died in birth. Those who died defending us in the world. We stand shoulder to shoulder, adorned in kahu-kuri. Where once the tekoteko kept all at bay, demanded they wait at the gate, commanded respect, now it is just us; the women whose children have died, the men whose children have died, caught with their foot perpetually raised behind. This is the front line. You may no longer come in.

You, our girl wails, you must listen. Hear the roar of the cicada, we say. Sing girl, sing. Her toes are dug into the flesh of Papatuanuku. You, rise up, she calls. Make noise. Get off your knees and make noise.