- Published: 5 July 2022

- ISBN: 9781760899554

- Imprint: Puffin

- Format: Paperback

- Pages: 336

- RRP: $16.99

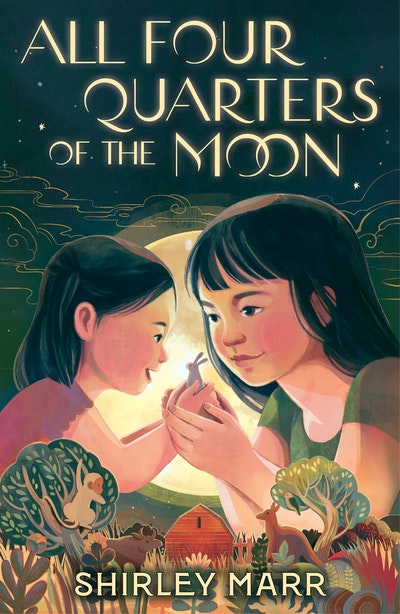

All Four Quarters of the Moon

From the CBCA award-winning author of A Glasshouse of Stars

Extract

First Quarter of the Moon

‘Ah Ma told me that in the beginning there was nothing. Then there was an egg,’ said Biju dramatically. ‘A giant hatched out of the egg and started to push the heavens and the earth apart. That’s how the universe was created.’

‘Is that so?’ said Peijing, thinking carefully. ‘If there was nothing, then what created the egg?’

‘Shhh,’ said Biju. ‘You’re ruining the story. Anyway, that’s not how the story really goes.’

‘Well, how then?’

‘In the beginning there was an egg and out of it hatched two sisters.’

Chapter One

Ah Ma said she could tell if the mooncakes she was making that year for the Mid-Autumn Festival would be perfect or not just by the feel of the yolk. She had peeled the salted duck egg and weighed it with her hand. It was a good egg. She passed the golden middle to her granddaughter.

‘Oh no,’ said Peijing. Eager not to drop it into the sink, she had held on too tight. Now the yolk lay misshapen in her palm, no longer a miniature full moon.

Peijing looked out the kitchen window at the real full moon, hanging so yellow and round that it almost sat on top of all the apartment buildings surrounding their own. She felt as if the moon would drop out of the sky if she so much as breathed wrong.

The Guo family were very superstitious. There were things forbidden during the festival. Don’t point at the moon or the Goddess living there will cut your ear. Don’t stare at the moon if you have recently given birth, got married, done a bad deal in business or have too much Yang energy in your body.

No one could ever explain properly to Peijing what this Yang energy was.

‘As the old proverb goes,’ replied Ah Ma, ‘There are no mistakes in life, only lessons.’ She smiled mysteriously and passed Peijing another egg yolk.

Ah Ma showed her how to wrap the washed yolks in lotus paste to make the mooncake filling. Peijing let out a breath she didn’t even know she was holding. Ah Ma gently touched her on the shoulder and she felt like they were sharing a secret.

The Guos were also a very traditional Chinese family who didn’t believe in touching or hugging each other because it wasn’t an honourable thing to hug or touch each other. But sometimes, as Peijing discovered, there were cracks in the rules for those who were very young and very old.

Out through the arched doorway that looked into the living room, where all of Peijing’s aunts and uncles had come to play Mah Jong, she could hear the shrill voice of Second Aunty saying that she had to leave already. Second Aunty cleaned the airport for a living and had to wake up at five in the morning.

This was followed by the sound of crying. Peijing peered through the doorway and there was Ma Ma with her face in her hands, looking vibrant in her new green housedress, but sounding as sad as a piece of tinkling jade.

It was definitely forbidden to cry during the Mid-Autumn Festival. Although Peijing was eleven years old now and considered herself far from being a child, she still didn’t understand why adults would tell others not to do a thing and then do it themselves.

But it was no good, Second Aunty still had to wake up at five in the morning. Second Aunty told Ma Ma to stop crying. To think about how Ma Ma and her family were moving to Australia the next day. The move would improve Ma Ma’s Yin energy. It would be a lucky life. Not like Second Aunty waking up at five in the morning, six days a week, to pick up disgusting things travellers left behind on aeroplanes. They didn’t forget to take just their magazines, you know.

Peijing felt the nerves in her stomach. Block 222, Batu Bulan East, Avenue 4 was the only home she had ever known.

She looked out the kitchen window to the playground. It was small and surrounded by the tall apartment blocks on all four sides, and kids would often fight to use the equipment, but Peijing liked how it felt contained and protected against the outside world. Safe. She could see her younger cousins strung out on the climbing frame, lighting up the night with sparklers like a constellation – even though they were definitely not allowed to play with matches. On the highest point of the frame, atop the rocket-ship slide, sat Peijing’s little sister, five-year-old Biju, fearless against the dark.

‘Come and help Ah Ma do the next step,’ said Ah Ma gently.

Peijing was sure ‘help’ was too generous a word for her grandmother to use, as rolling out the sweet mooncake pastry was the hardest part. She was unsure if she could ever get it as thin as Ah Ma did without making a hole. She declined the rolling pin Ah Ma passed to her.

‘How long have you been making mooncakes for?’ asked Peijing, surprised that she had never thought to ask before.

‘The womenfolk have always been making them as long as I’ve known,’ replied Ah Ma. ‘My mother taught me, and her mother taught her. I can even remember my great-great-grandmother making them. It’s the same family recipe.’

Ah Ma leant in closer to Peijing. ‘The secret lies in the homemade golden syrup.’

Peijing marvelled at Ah Ma’s long memory. She felt a strange sensation about being the last on a long chain of these mooncake-making women, little Biju showing no interest in mooncakes other than eating them. Peijing felt anxious that she could only do the easy bits, as if time might just run out before she could learn to do it all.

That’s if anyone made mooncakes in Australia anyway.

She had overheard conversations about how different things were going to be for Ba Ba, Ma Ma, Ah Ma, Biju and her once they arrived. How they would have to learn new ways and new customs. How the stores there might not even sell salted duck eggs.

She wondered what they made for Mid-Autumn Festival in Australia. If they celebrated Mid-Autumn Festival at all.

Ah Ma pressed the pastry and the filling into the wooden moulds and Peijing watched as the mooncakes tumbled out, perfectly shaped and imprinted with mysterious designs on the top.

‘What about these designs? What do they mean?’ Peijing asked, tracing the top of the mooncakes with her finger before hiding her hand behind her back.

‘That I don’t know. These meanings have been lost in time. That symbol is so old that even someone as ancient as me can’t understand it.’ Ah Ma chuckled and dabbed the pastry with an egg wash. ‘It is from before the first written language, when our ancestors used to pass stories from mouth to ear and try to hold them safe inside symbols. Stories would stay for eight thousand years, then stories would fade.’

Peijing had been learning about the universe at school – the big bang, the first stars, the first single-celled life – and she knew, in the scheme of things, eight thousand years was just a blink of an eye. She was worried that this precise moment would disappear and would never come back again.

‘But as the old saying goes,’ continued Ah Ma, ‘The palest ink is better than the best memory.’

A written story could last forever. Peijing wasn’t very good at writing her feelings down and she worried about that.

As the mooncakes baked away, Biju suddenly made her grand entrance into the kitchen, plum sauce from the duck she had eaten for mid-autumn dinner still around her mouth, her clothes smelling like firecrackers.

‘I want one of those,’ she said loudly, peering through the glass into the oven.

She did not say please. Manners were also very important to the Guos. As the eldest daughter, Peijing was a mirror; a reflection of her mother. So she was always careful about how she behaved. As her younger sister, Biju was a reflection of Peijing.

Well, supposed to be, anyway. Pejing pressed her lips together and sighed.

‘Then you’ve arrived just in time.’ Ah Ma smiled. She didn’t mention anything about Biju not saying please. She pulled the hot rack out of the oven with a dishcloth.

Peijing looked at all the perfectly baked mooncakes in wonder and she felt golden and magical. Biju placed her arms around Ah Ma and sank her face into Ah Ma’s apron. Peijing wished she was still small enough to do the same.

‘Let’s see how they turned out.’ Ah Ma placed one on the cutting board and fetched a knife.

Peijing found herself holding her breath again. As if her whole life depended on this moment. Ah Ma sliced down with the knife and pulled the two halves apart.

It was perfectly baked.

The yolk in the middle round and yellow.

Peijing let go and took a breath.

‘Yuck!’ yelled Biju. ‘I hate the ones with the stinky egg!’

As abruptly, the thin webbing that held the magic together, where the middle of a mooncake could be as big as the moon, was destroyed. Peijing knew Biju was only five and couldn’t help it, but she wanted to remember this moment as perfect.

Ah Ma divided the mooncake into four pieces. Peijing picked up a slice and looked at the yolk, now a quarter moon, and felt haunted for reasons she could not explain. A cold, empty feeling like the vacuum of space. She popped the piece into her mouth. It tasted delicious. Salty, sweet and crumbly.

‘Don’t worry. I’m going to make your favourite filling next. Sweet red bean with pumpkin seeds,’ Ah Ma said to Biju.

‘Why didn’t you make my favourite first?’ Biju demanded and scrunched up her face. ‘I might be asleep by the time they finish cooking!’

Peijing sighed again. She always seemed to be sighing at one thing or another, carrying the weight of one responsibility or another on her shoulders. Biju, on the other hand, understood none of these things.

‘My apologies. Ah Ma got it the wrong way around. Ah Ma is forgetful these days.’

Biju suddenly went quiet.

‘I was really looking forward to eating my last mooncake here,’ she said and sucked on her fingers. ‘We don’t know if anyone even makes mooncakes in Australia.’

And with that, it felt like the universe connected the two sisters again. Peijing’s heart softened.

‘Can I help with anything?’ Ma Ma appeared in the kitchen, rubbing her face. Peijing did not want to tell her mother that one set of fake lashes on her perfectly made-up eyes was missing. Ma Ma was holding a Mah Jong tile in her hand. She deposited it absentmindedly on top of the fridge.

Peijing stared up at the symbol for the East Wind.

Ah Ma set Ma Ma to work straight away rolling pastry. While they were busy chatting, Peijing took her sister by the hand. Together they slipped past the adults playing Mah Jong, to their shared bedroom. Their bare feet moved faster as they approached the door.

To a world of their own.

‘In the beginning there was an egg and out of it hatched two sisters,’ declared Biju. ‘They stood on either side and pushed up the sky together. So high up that heaven and earth would never meet again.

‘Their imagination created all the animals, their tears created the rivers, the blackness of their hair the night sky and the twinkle in their eyes all the stars. Oh, and the Big Sister’s flaring temper created fire.’

‘Yes, that is true,’ said Peijing, ‘but you got the wrong sister.’

‘I don’t think so!’ replied Biju in a huff.

All Four Quarters of the Moon Shirley Marr

A big-hearted story of love and resilience from CBCA award-winning author Shirley Marr, starring sisters and storytellers Peijing and Biju, a lost family finding their way, a Little World made of paper, a Jade Rabbit, and the ever-changing but constant moon.

Buy now