Paula Hawkins’ psychological thrillers: several million opinions and counting.

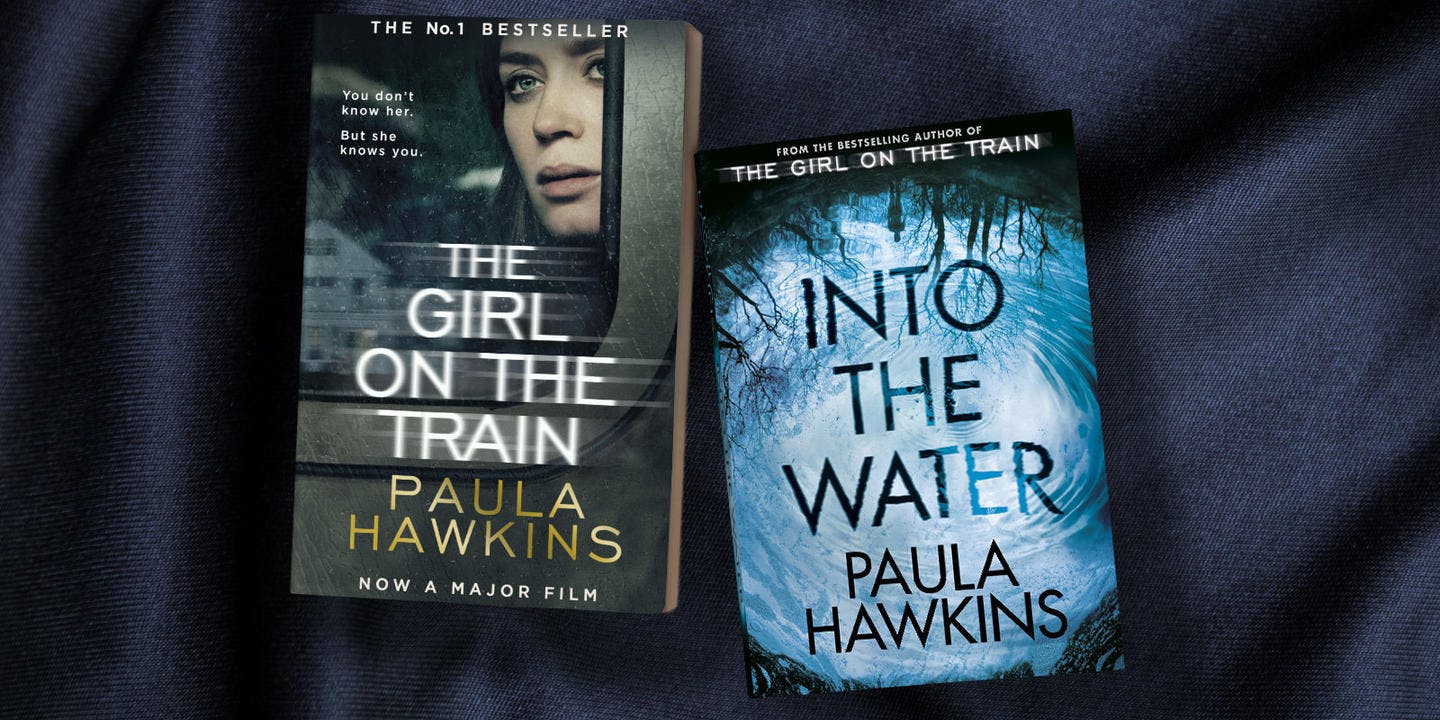

The Girl on the Train, Paula Hawkins’ gripping story of love, obsession and murder, was a runaway success, smashing records and selling more than an astonishing 18 million copies worldwide. It also occupied the No. 1 spot on the UK hardback chart for 20 weeks, the longest run of any book previous. Faster than a speeding bullet, The Girl on the Train won over critics, with many labelling it the thriller of 2015. All the while word-of-mouth travelled, elevating the book into ‘must-read’ territory. Stephen King loved it (‘A really great suspense novel. Kept me up most of the night.’), as did Marian Keyes (‘A long, long time since a book gripped me like this.’).

Hawkins has said she wrote the first half of the book about a woman who sees something unsavoury on her daily commute very quickly. The story was also adapted by DreamWorks Pictures into a movie starring Emily Blunt in lightning-quick time – debuting in cinemas a mere 20 months after the book’s release. It was a box-office smash, grossing almost four times the film’s $45 million budget.

The Girl on the Train brought all the chills and thrills expected of a page-turning thriller, but also offered a fresh, ‘domestic’ take on a genre long dominated by serial murderers, granite-jawed detectives and gore. ‘I think people have got a little bit tired of a trope of a beautiful dead woman on the first page of a novel,’ Hawkins said in an interview with The Guardian. ‘It’s more the psychology of crime going on. They don’t tend to be so much about violence or about bloody acts.’

‘Domestic noir’ is a term attributed to British author Julia Crouch, and one that’s been liberally applied to Hawkins’ writing. In a nutshell it refers to the exploration of the darkness that exists behind the shiny, happy social-media facades of our modern lives; and the locked doors of our suburban homes. If it’s a truism that novelists should use their platform to reflect the issues of our times, then indeed domestic violence should not be shied away from. And, thankfully, authors like Hawkins are opening the doors to exploring the horrors that exist all around us.

Just two years on from Hawkins’ propulsion to global notoriety, she releases her second novel, Into the Water. Set in the northern English town of Beckford, the mystery lingers around an infamous waterhole that, due to the deaths of several women, has been dubbed the Drowning Pool. But is it a suicide spot or some kind of dumping ground? This time Hawkins explores the murky territory of the stories we tell about our pasts and their power to destroy the lives we live now. Unsurprisingly, DreamWorks were keen to secure the film rights to Into the Water, and took out an option months before the novel’s release.

‘This story has been brewing for a good while,’ Hawkins said in a statement. ‘For me there is something irresistible about the stories we tell ourselves, the way voices and truths can be hidden consciously or unconsciously, memories can be washed away and whole histories submerged.’