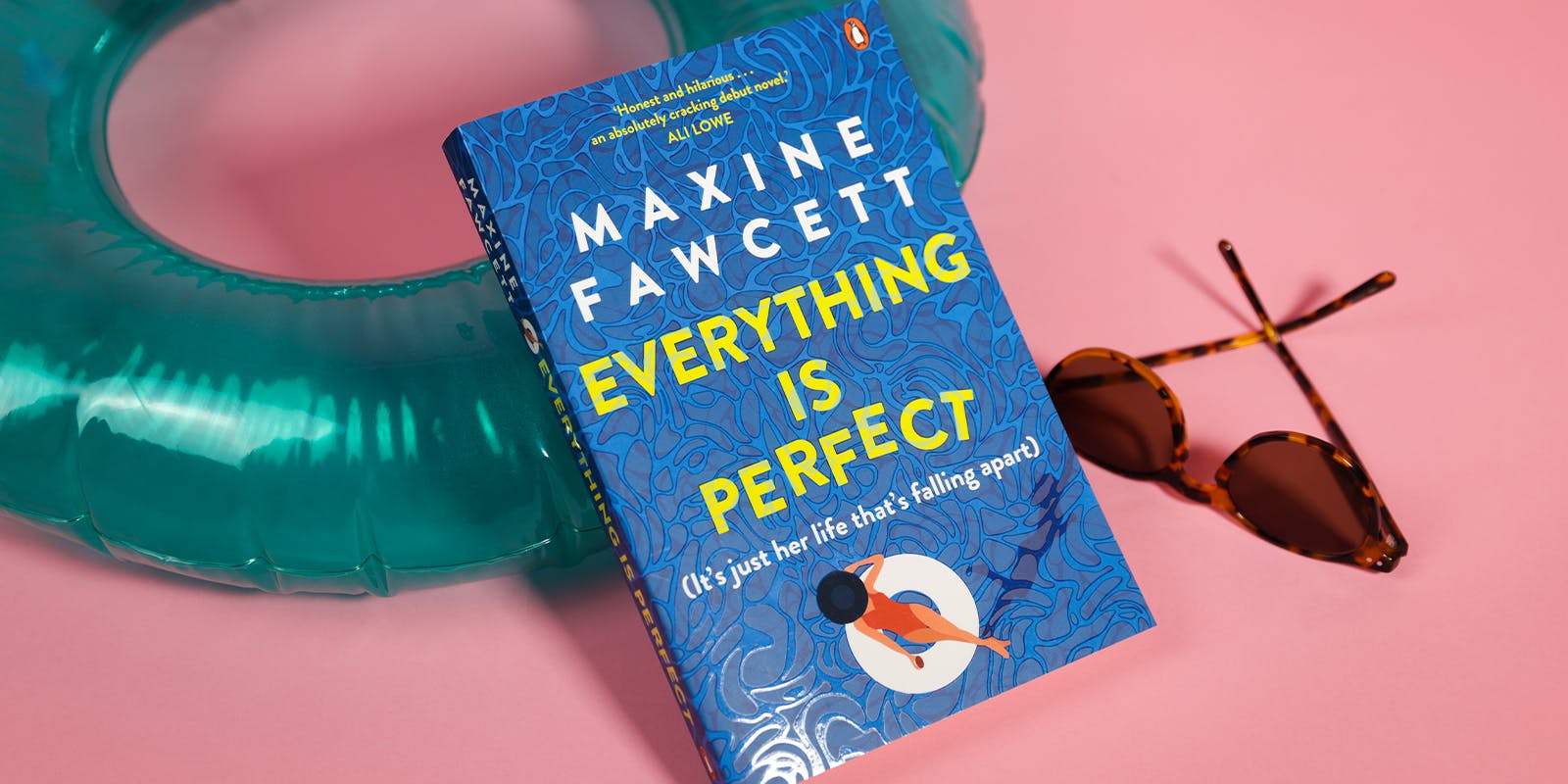

Ahead of Mother’s Day, author of Everything is Perfect, Maxine Fawcett, shares how she has come to embrace the imperfections of motherhood.

I’ll never forget the first time I looked into my newborn son’s brown eyes. His warm naked body was on my chest, his eyes blinked slowly at me, and it was like he was trying to say,

‘I hope you’re going to be good at this!’

Bloody hell I thought. I hope so as well. He seemed so wise while I had no idea what I was doing. Was I going to get this right?

I used some of this memory in my debut novel Everything is Perfect. Cassandra Prince (as well as believing a widowed dad at her kids’ school is the answer to her problems) is struggling with memories of her childhood and her relationship with her own mother. She’s trying to do the best for her children, Ellie and Danny but constantly questions her choices as a mum in her struggle to be perfect.

A week after the birth of our son, we made it home. I ventured outdoors for brave walks to the beachfront with leaking and bleeding nipples and the obligatory dip in hormones that even my morning coffee couldn’t salvage. I took him to mothers group, a chance to swap war stories and make new friends. This did happen (two wonderful women who came to my book launch earlier this year) but there was also the other stuff.

‘Your son’s head looks strange on one side. Have you noticed?’ Is what one woman said to me on week two. I’d raced up the hill to our apartment (my c-section stitches bursting at the seams) and googled ‘baby head deformity’ before booking him in for an urgent appointment.

‘Your son’s head is totally normal,’ the doctor said. I’d exhaled (not sat next to that woman again) but the thought was still there. I’m failing at this. I should have taken him for a check-up before someone pointed it out! Then the questioning began. Why was their baby crawling while mine shuffled around on his bum? Wasn’t he meant to be talking by now? It’s okay, I’d tell myself in my sane moments. Every baby develops at a different pace, but the niggle would still be there. That I wasn’t doing a good enough job.

In the primary school years, the façade of what it means to be the ‘perfect’ mother continued.

‘We spend an hour a day doing sight words,’ is what one school mum said to me in kindy. My son was lucky if we spent ten minutes.

‘I hate karate,’ my oldest said. This came after years of me sitting watching him every week, full of encouragement and trying to get him to carry on.

‘I don’t like reading,’ said the other. When I’d patiently read to him every night from birth to the age of thirteen. I thought I’d succeeded with the reading thing, had given myself a mental high five but it seemed not.

I’ve uncovered and shown every part of myself since becoming a mum. At times the sensation is so raw, it’s like the skin has been stripped back to the bone. I’ve learnt about the horrible parts of myself, when I lose my patience and feel like my head is going to explode. Compared to the high of realising my empathy far surpasses what I thought it was.

Now my sons are teenagers, I’ve made peace with not being perfect – it’s an aspiration impossible to attain. My youngest will put on a silly voice making me laugh and my oldest will call from his latest outing just to check in. I know I’ve done and am doing the best I can. Like Cassie, I’ve come a long way. They’ve taught me who I am, and I wouldn’t change it for anything.